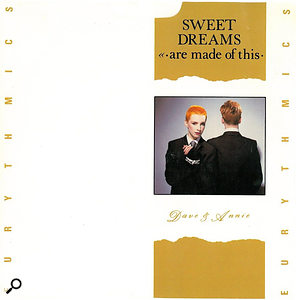

Begun as an experiment, ‘Sweet Dreams’ launched Eurythmics to international stardom and is still filling dancefloors to this day.

With its strident electro beat and pulsing analogue synth riff, topped with Annie Lennox’s hooky, almost sinister nursery rhyme‑like vocal, Eurythmics’ 1983 single ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ is an instantly recognisable track that became a Top 10 hit the world over, reaching number two in the UK and number one in the States. Produced and co‑written by Dave Stewart, Lennox’s partner in the duo, it was the breakthrough song that made their careers, ending a run of five flop singles.

Still, ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ was anything but a calculated attempt to have a hit, being a three‑and‑a‑half minute pop song which broke with traditional structure by essentially having no chorus (its verses providing the hookline). At first, even Eurythmics’ paymasters at their record label RCA weren’t convinced that the track was strong enough to be a single. “The record label were not really interested in us,” Stewart remembers today. “I kept going in there and I’d say, ‘Look, we’re doing really great things.’ They just couldn’t understand it.”

Still, ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ was anything but a calculated attempt to have a hit, being a three‑and‑a‑half minute pop song which broke with traditional structure by essentially having no chorus (its verses providing the hookline). At first, even Eurythmics’ paymasters at their record label RCA weren’t convinced that the track was strong enough to be a single. “The record label were not really interested in us,” Stewart remembers today. “I kept going in there and I’d say, ‘Look, we’re doing really great things.’ They just couldn’t understand it.”

All of that changed with the song’s release in the UK on 21st January 1983, when Eurythmics brought a dash of colour, femininity and soul to the mainly bloke‑ish world of ’80s synth pop. What had initially started out as Stewart and Lennox’s experiment with synthesizers and an eight‑track tape machine above a picture framing shop in London’s Chalk Farm went on to become a timeless pop and club anthem. “All hell let loose,” says Stewart. “Every country in the world was playing ‘Sweet Dreams’, from Norway to Australia to Israel... it didn’t matter where.

“We were in a little bubble away from anything that was going on in the pop music world. So that’s why we didn’t sound like anybody in the pop music world at the time.”

Experimental Phase

Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox were no strangers to the charts, having enjoyed two hits with their previous band the Tourists: their 1979 cover of Dusty Springfield’s ‘I Only Want To Be With You’ and its 1980 follow‑up, ‘So Good To Be Back Home Again’. The pair weren’t the main songwriters in the Tourists, however, with that role being taken by the band’s guitarist/singer Peet Coombes.

Stewart admits that there was some creative frustration in the Tourists for the duo (at the time also a couple), along with tensions exacerbated by Coombes’ problems with drugs and alcohol. “Pete was very prolific,” he says. “I met Pete and was just actually jamming and messing around at the beginning, but I realised very quickly, 'Wow, this guy is a great songwriter'. But as we got going with Annie as well, Pete’s sort of addictive side got so difficult to work with. He was the sweetest person when he wasn’t drinking or having to take whatever he was taking.”

After Coombes collapsed while the band was on tour in Australia in 1980, the Tourists split. On the same trip, in a hotel room in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Stewart began playing around with EDP’s Wasp synthesizer, accidentally stumbling upon the future, more electronic direction that he and Lennox were to pursue as Eurythmics. “I could actually get some interesting things happening,” he says. “Y’know, like, sequenced little sort of random hold patterns that sounded very exciting to us, even though it was just coming out of the plastic speaker in a crappy hotel room in Wagga Wagga. We weren’t even writing songs, I was just messing about on it.”

On the flight home from Australia, an utterly shattered Lennox and Stewart, who were sharing a flat together back in London, agreed to end their romantic relationship, while continuing to work together. “I remember our conversation,” says Stewart. “It wasn’t even a long one, ‘cause we were so exhausted. She goes, ‘Y’know what? We should probably try living separately for a second or whatever?’ And we both went, ‘God yeah, we should,’ and then we fell asleep. We went back to our flat and then Annie moved upstairs, just literally one room above. So we still saw each other all time.”

Soon after, Lennox travelled to her native Scotland to visit her parents, leaving Stewart with time alone to further his experiments with the Wasp, pairing it with EDP’s matching proto‑sequencer the Spider, and a TEAC 144 Portastudio. “I kind of voraciously learned how to use that really quickly,” he says of the latter, “and I realised it was little miracle. I had done things before, even before I met Annie actually, where I’d managed to get my hands on a Revox tape recorder, and I’d bounce things in a really crappy way, back and forth, and make a kind of montage of stuff.

“But with this Portastudio and the Wasp and the Spider sequencer, and then the [Roland TR‑606] Drumatix, in one way or another I managed to manipulate the drums and the sequenced keyboard together. Then I was able to choose which sections I’d sequenced and sort of fly them over and bounce them. So I’m recording on track one with the sequencer, but then I’d sort of send it to track three or four and then I could switch it in and out when I didn’t want it. I could drop in if I wanted to change to a different chord or note or sequence. So I kinda built a track, kept bouncing back and forth. Some of them became the actual tracks on the Sweet Dreams album.”

Before that was to happen, though, Stewart learned key lessons about recording from Conny Plank (Kraftwerk, Neu!), the Cologne‑based producer of Eurythmics’ 1981 debut album, In The Garden, along with a guesting Holger Czukay from Can. “Some of it was from the ideas of the little demos on the Portastudio,” says Stewart. “Conny Plank taught me how him and Holger Czukay took no notice of anybody, and to just distort things if I wanted or record anywhere I wanted... hang mics out the window.”

While In The Garden failed to set the charts ablaze, its sonic adventurism saw the synthesizers begin to creep into Eurythmics’ psychedelic guitar pop on tracks such as ‘Take Me To Your Heart’ and ‘She’s Invisible Now’. By the time of 1982’s ‘This Is The House’ and ‘The Walk’, both stand‑alone singles released ahead of the Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) album, the duo had gone almost fully electronic, working in their ad hoc Chalk Farm studio set up by Stewart and Adam Williams (former bassist of the Selector) with a budget of £5000. “We looked at the cheapest things we could get second‑hand,” Stewart remembers. “It added up to about £4800, which we didn’t have. So I went to see the bank manager with Annie, and he miraculously lent us £5000. Even though we looked like complete nutcases [laughs].

“So now we had a very basic thing — Tascam eight‑track, a Bel noise reduction unit which I used to use compress Annie’s vocals by switching it in and out on the vocal track. Then a Roland Space Echo and a Klark Teknik [DN50] spring reverb which we kind of dismantled and did all sort of experiments with, and a second‑hand Soundcraft desk.”

For ‘The Walk’, Stewart transferred some of its parts directly from the TEAC Portastudio onto the Tascam eight‑track tape. “You only had seven tracks,” he says, “‘cause track eight had timecode. ‘The Walk’ has got me playing the bass line on a Roland SH‑101, and then there’s all these vocals and a trumpet solo by Dick Cuthell who was playing with the Specials. It has a lot of things going on, on seven tracks. It’s got about 36 things... you would need a 48‑track really. But you had to sort of decide and bounce them on the spot.

“So Annie and Adam and I had maybe done three vocals grouped together and we had to bounce them to one. Then do another three and bounce them on to another track, and then bounce the six vocals onto one track again, so they sounded like a kind of gospel‑y backing. Y’know, we went through all this kind of learning curve of everything about recording.”

The control room of what would go on to become The Church Studio.

The control room of what would go on to become The Church Studio.

Highs & Lows

But it was with Stewart’s £2000 purchase of a MkI Movement Systems MCS Percussion Computer that his beats progressed to the next level. Only around 30 were ever built and the musician/producer had one of the first off the custom production line. “The guy lived in Bridgewater,” he recalls, “and we had to sleep on his floor for a couple of days while this prototype was being finished. But you could actually make drum patterns and see them for the first time on a little black and white screen like a heart monitor.”

It was one of his initial trials with the MCS that produced the distinctive beat on ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’. “There was thing on it where if you had a tom‑tom sound, you could just turn a knob and tune it all the way down to sound like a huge drum that you would bang on a ship to get the people rowing. That’s what I did on ‘Sweet Dreams’. The first downbeat, the doom, was actually a mistake, ’cause the bloody drum computer kept doing the opposite of what I was trying to do. But then I thought, Ooh that actually sounds much better than what I was trying to do. That low drum, y’know, it’s good ‘cause it’s not boomy. It’s like a thud, but it’s so low. And then with the [four on the floor] bass drum on top of it, still to this day, you put it on in any club and everybody gets up.”

In the writing of ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’, however, Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox were in very different frames of mind. Stewart was strangely elated, having just survived a near‑death experience on an operating table when having a punctured lung repaired. “It sounds corny,” he says, “but I did have that thing where I could see myself downwards from above and not really understanding what was happening, but then coming ‘round. I was a completely changed person. I just came out like somebody had plugged me into an electric socket, and I’ve been like that ever since [laughs]. So during the whole making of ‘Sweet Dreams’ I was on fire, positive, full‑on.”

Lennox, meanwhile, was suffering a low, inspiring the song’s deceptively jaded lyric, which was written quickly in a half‑hour burst when she heard the track that Stewart was working on. “Annie won’t dispute this,” says Stewart, “but she was actually feeling really down and often quite depressed and lost. I kept up with the drum beat, and I also had half of the sequence. Annie sort of leapt off the floor and was like, ‘What is that?’ And she got on the [Oberheim] OB‑X. Annie had a string sound that we liked on there, and then she played that riff on top of what I was playing and the two synthesizers together with that drum beat made this unbelievable thing.

“The drum computer was triggering a sequence into the Roland SH‑101 that sounded powerful, and the Oberheim was more of a soft string sound that we managed to cut off so it made it more attacking. I think it was actually a preset, I don’t think we made the sound. The Roland is playing the original sequence and then Annie was playing in between it. ‘Sweet Dreams’ always confuses keyboard players when they try and play it, because they don’t realise it’s actually two keyboard parts that are playing completely different things.”

The Church

Before the track could be completed, though, Eurythmics lost their studio space above the picture framers. The duo’s operation then moved into what was to later become The Church Studios in Crouch End, the building at the time owned by animators Bob Bura and John Hardwick (of Captain Pugwash and Trumpton fame).

“They’d actually bought that church ‘cause they needed a big space so they could make big wide shots,” says Stewart. “The floor had to be very sort of solid to use all the tracking things they were using. I went back to Annie and I said, ‘Well, you’re not gonna believe this, but I think I’ve got a place where we can finish recording.’ It was pretty hard to believe because they didn’t even want to charge us any rent. But they actually enjoyed us being there and making this music.”

Another view of The Church control room.

Another view of The Church control room.

Initially though, the small space that Lennox and Stewart had at the church was a ground‑floor cloakroom, which was crammed with their Soundcraft desk, Tascam eight‑track and ever‑growing collection of synths. “We only had one Beyer stick microphone often used for hi‑hats,” says Stewart. “That was the mic that I had to record Annie’s vocal.

“It was all ‘necessity is the mother of invention.’ So the reason why our records sounded sort of weird was ’cause we didn’t really have any money. In the middle of ‘Sweet Dreams’, you can hear me and Annie playing milk bottles. It was me and Annie pouring out the water ’til we got them in tune and then actually going, ‘Oh should we tap them with a piece of wood, or a piece of metal?’ Just experimenting ’til we could actually get the sound we wanted.”

This handmade approach extended to the other tracks on the Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) album. “‘I’ve Got An Angel’ is basically the drum machine with a Space Echo, mixed with a real‑played vibraslap,” says Stewart. “Then banging a huge plank of wood, and sending that to the Klark Teknik with the reverb full on and taking away the original signal. For handclap sounds we would just get something like an open hi‑hat from the drum computer and then stand around the mic and clap and send those into a [Electro‑Harmonix] Big Muff fuzzbox pedal, with the least amount of fuzz possible. Then I’d mix it with the original recorded sound to try and create a clap that sounded a bit white noise‑y.”

In pushing their eight‑track setup to the limits, mixing sessions were typically all‑hands‑on‑desk affairs. “It was funny because it was always me, Annie and Adam, we had three channels or something each on the desk, with bits of tape and marks written on them, like everyone did in those days. And at 37 seconds, it’d be like, this has to go down because suddenly the backing vocals are not on it and it’s a drum, and then the backing vocals come back on the same track. It was just all crazy. But obsessively trying to get it right, y’know.”

Scaling Up, Scaling Down

After the international success of ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’, Eurythmics could suddenly afford to expand their recording setup. Fortuitously, around the same time, the ever‑generous Bob Bura and John Hardwick offered Eurythmics a bigger space. “They realised we were really cramped,” says Stewart. “They said, ‘Hey look, we’ve got an idea. There’s this other room next to where we’re working, and we could actually just build one wall and the space would be about three times bigger than where you are.’ So they did it themselves by hand with bricks and cement. We were like, ‘Fucking hell, these guys are so nice. I don’t know why they’re doing all this stuff for us.’”

Nonetheless, gear‑wise, with the money from ‘Sweet Dreams’ yet to roll in, the duo were still working with a restricted budget for their second album of 1983, Touch. “There was a great place which was a second‑hand recording equipment exchange and buy,” Stewart explains. “We took the Soundcraft desk up there and exchanged it for a slightly bigger desk, so we could have more inputs. And we got a second‑hand 24‑track Soundcraft tape machine. It was all the cheapest things you could buy, but we knew it was more about how we were gonna record stuff on to it that would make it sound great. Like, finding an old bass drum at a jumble sale and tapping it with a wooden spoon and recording it with a mic 20 feet away in a big echoey church. That’s gonna be making the sound a lot more different than a tape recorder that was £100,000, as opposed to £8000 or something.

“We had a few more mics because by then we’d done a world tour of Sweet Dreams and we’d bought equipment for live. Then I went, ‘Well, we could use it also for recording.’ So we had a mixture of things and we had another guy helping called John Bavin. He was an engineer and he said, ‘Hey, you should get one of these,’ and we’d get one of them. But not much more. In fact Touch was really handmade again.”

Dave and Annie during a photoshoot.By this point, Eurythmics had also acquired a Roland SH‑09 and Juno‑60, plus the relative luxury of a small vocal booth, though the control room remained a tight squeeze. Incredibly, then, the recording of the strings on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’, their 1984 transatlantic Top 10 hit, involved a bizarre setup to accommodate all of the players being conducted by Michael Kamen.

Dave and Annie during a photoshoot.By this point, Eurythmics had also acquired a Roland SH‑09 and Juno‑60, plus the relative luxury of a small vocal booth, though the control room remained a tight squeeze. Incredibly, then, the recording of the strings on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’, their 1984 transatlantic Top 10 hit, involved a bizarre setup to accommodate all of the players being conducted by Michael Kamen.

“I forgot to tell him that we only had about four mics,” Stewart laughs. “He came with an orchestra and we had nowhere to put them. So he was like, ‘Oh Jeez, how am I gonna do this? How do I even see them to conduct them?’ Because cellos were in the toilet and the violin players were in the corridor and he was hanging off a sort of spiral staircase. We were recording it down to mono, but it sounds bloody incredible.”

By 1984, with Bura and Hardwick having decided to sell up, Eurythmics bought the entire building and renamed it The Church Studios. “We then decided that The Church could be everything,” says Stewart. “We could rehearse in there, we could store our gear in there, we could have our wardrobe in there, we could record albums in there.”

But with ongoing building work clashing with the recording of their fifth album, the soul/rock of Be Yourself Tonight, Eurythmics decamped to Paris and reverted to a similar setup as they’d used on the Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) album. “I said, ‘Actually let’s go back to the eight‑track,” remembers Stewart. “‘I think we’ve gone too big with 24 tracks.’ We took the eight‑track to Paris and hired a little room in a youth club in this really obscure Russian quarter on the outskirts, for something like 10 pound a week. I rang Adam and said, ‘D’you want to come and have a reunion, recording like we did on the Sweet Dreams album, in Paris?’ So he came and it was just back to the basics. We had the same bloody little things, but we brought Dean Garcia in to play the bass and then we brought in Ollie Romo who had a kind of synthesizer drum kit, ’cause the room was back to the size of the cloak room at The Church.”

Legacy

In 1990, having become a multi‑platinum‑selling international phenomenon (with total album sales currently standing at 75 million), Eurythmics split. “It was exhaustion,” says Stewart. “Exhaustion really of each other as well as exhaustion generally. It was like, Hang on, I must have some kind of life going on outside of Eurythmics, otherwise we’re gonna go bonkers.”

Stewart had already embarked upon a parallel career as a producer for the likes of Mick Jagger, Tom Petty, Bob Geldof and Feargal Sharkey, and would go on to oversee records by Bryan Ferry, Ringo Starr and Stevie Nicks. “While I was making Eurythmics records, I kept getting asked to produce other people, and mostly turned it down, ’cause I didn’t have time and I was obsessed with making Eurythmics great. But I would do the odd thing. And that’s how Tom Petty’s ‘Don’t Come Around Here No More’ and all these kind of different things came out. I would do the odd thing under different names — Boo Boo Watkins, Jean Guiot, Raymond Doom [laughs].

“But I did learn everything really from the bottom up, from Portastudios all the way through to the point where I then liked to have an engineer, so I could think straight about the song and the artist I was working with.”

While Eurythmics reunited for a one‑off album, Peace, in 1999, and got together in 2014 to perform ‘The Fool On The Hill’ at a Grammys tribute to the Beatles, Stewart says there are currently no plans for any future activity for the duo, aside from the current vinyl reissues of their first three albums.

“The thing is I would love to do a concert tour with Annie,” says Stewart. “Obviously our fans would love it, ‘cause they’re on Facebook and everything, going, ‘Yeah I know you’re putting vinyl out, but when are you gonna play again?’ So I much more want to do this, but Annie has her reasons why she thinks it might be a bit overwhelming.

“Obviously the Eurythmics thing could be huge arenas. But it could actually be anything. It could be at the Sydney Opera House with an orchestra. It could be the two of us with just electronic gear, which I would quite like... basically us virtually back to almost ‘Sweet Dreams’ sequencing, showing the actual stripped‑bare electronic Eurythmics songs. I’ve done a few experiments like that. I don’t think anything’s likely, ’cause Annie doesn’t want to do it. But on the other hand, that’s how she is feeling at the moment...”

Whether or not Eurythmics ever get back together, Dave Stewart has his own opinions about why ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ has become a classic track. “I think it’s because of that experimentation and that it wasn’t trying to be a single or a hit or anything,” he says. “It was just, 'Oh my God, this is such a weird experiment'. Then the experiment turned into a song, then the song turned into actually a whole world. I mean, it’s like, every morning I just get told, ‘Oh there’s like 20 new remixes of ‘Sweet Dreams’.’ Literally every day.

“My mate James Barton, who created Creamfields, he’ll send me a video text when he’s at a festival and there’s 50,000 people singing ‘Sweet Dreams’. At every one of them, at some point, it appears.

“‘Sweet Dreams’ just became ‘Happy Birthday’ basically, in a way,” laughs Stewart. “It’s everywhere you go.”

The 2018 vinyl reissues of In The Garden, Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) and Touch are available now on Sony Music.