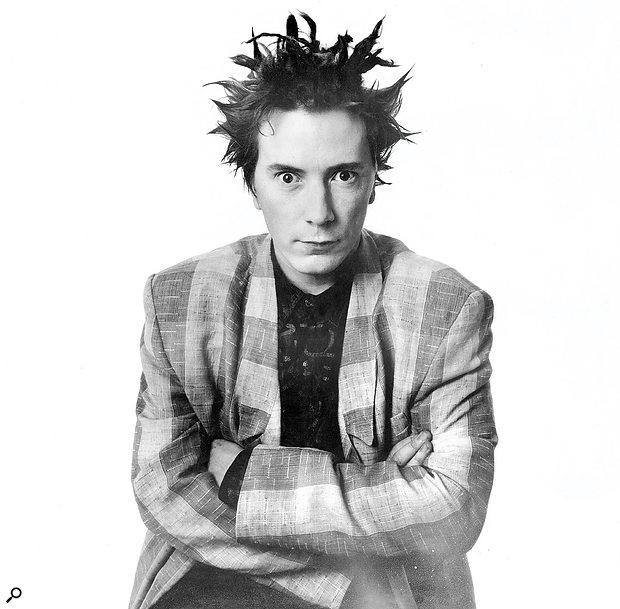

In 1985 John Lydon found himself in a New York studio with producer Bill Laswell and a group of session musicians. The result was to become one of PiL’s most recognisable tracks.

In 1984, the artist formerly known as Johnny Rotten was feeling “cast aside” and lost. It had been six years since John Lydon had escaped the wreckage of the Sex Pistols and formed Public Image Ltd, whose second album Metal Box in 1979 — with its primal screaming, dub bass and avant-garde guitar noise — had helped define post-punk. But over the ensuing years, successive line-ups of PiL had fallen apart and now Lydon, suffering from a rare moment of self-doubt due to a lack of support from his label Virgin Records, was wondering whether or not to quit the music business altogether.

“I didn’t know where I stood in the music industry,” Lydon says today. “The purse strings were being withheld and everything was difficult. PiL as a band was under real severe pressure and that pressure eventually cracked us and left me kind of stranded there. I didn’t know what really to do with myself.”

Enter Bill Laswell, the New York-based musician and producer whose own discography at that point included experimental punk-funk with his band Material, as well as production credits for Laurie Anderson (Mister Heartbreak) and Herbie Hancock (Future Shock). Come ’84, Laswell was working on a track with hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa which the latter thought could benefit from a cameo appearance by a rock singer. Laswell suggested John Lydon.

“The first two PiL records I thought were great,” says Laswell. “As a sound I always liked [bassist Jah] Wobble and I thought that [Keith Levene’s] guitar was very influential. Between the guitar and the bass they influenced so many bands. It minimalised all the references, you just heard the fundamental. So I was really into PiL.”

Together in BC Studio in Brooklyn, Laswell, Bambaataa and Lydon created the landmark 12-inch Time Zone single ‘World Destruction’, one of the first records to meld rap and rock. “It was done pretty spontaneously,” says Laswell. “The beat was the Oberheim DMX. The whole style in drum machines went from the 808 to the 909, and all the pop stuff was the LinnDrum, but the more raw hip hop stuff, most of it was the Oberheim DMX. So we went to the studio and Bambaataa had prepared some lyrics. We just made up a piece and then John came in.”

“Bam had the basics of his song,” says Lydon, “but he had no hook and chorus and bam in I came with the [sings] ‘Time zooone’ bit. The whole thing came together relatively quickly.”

For Lydon, the bringing together of rock and rap seemed an obvious fit. “The thing you’ve got to understand about Bambaataa is his DJ background,” he says. “As well as Parliament and Funkadelic and things like that, he was spinning Kraftwerk and there’d be the occasional mad rock tracks in there. So it wasn’t too difficult a journey for me. We had a similar love of different kinds of sounds.”

Following the release of ‘World Destruction’, Lydon and Laswell forged a plan to make the next PiL record together. Simply titled Album, it produced a number 11 UK hit in the shape of the hypnotic and heavy single ‘Rise’, featuring the singer’s “anger is an energy” hookline and memorable “may the road rise with you” chorus.

Album featured Lydon and the bass-playing Laswell alongside an impressive cast of session musicians including drummers Ginger Baker and Tony Williams, guitarists Steve Vai and Nicky Skopelitis, Fairlight programmer Ryuichi Sakamoto and electric violin-player Shankar. “I gotta say that working with Bill was a good pickup at that point,” Lydon admits, “and definitely making Album. The amount of A-league players that would come into the studio, and very willingly, was a refreshing reintroduction into why I love music so much.

“It proved to me that I could work with anyone,” he laughs. “The best of them as well as the worst.”

Bill Laswell

Producer Bill Laswell.Photo: Hiroshi OhnumaBill Laswell had first arrived in New York from his native Michigan in 1976 at the time when the downtown music scene in Manhattan was thriving. “The punk thing was raging,” he remembers. “But there were a lot of other alternative things happening downtown where you had lofts with people from jazz backgrounds playing kind of improvised music. That was going on at the same time as a lot of rock and electronic experimental things. It seemed to be at that moment it was all this kind of alternative music and quite a lot of it. It was an interesting period for New York. At that age, it was kind of overwhelming just the amount of activity that was going on.”

Producer Bill Laswell.Photo: Hiroshi OhnumaBill Laswell had first arrived in New York from his native Michigan in 1976 at the time when the downtown music scene in Manhattan was thriving. “The punk thing was raging,” he remembers. “But there were a lot of other alternative things happening downtown where you had lofts with people from jazz backgrounds playing kind of improvised music. That was going on at the same time as a lot of rock and electronic experimental things. It seemed to be at that moment it was all this kind of alternative music and quite a lot of it. It was an interesting period for New York. At that age, it was kind of overwhelming just the amount of activity that was going on.”

Within this scene, Laswell became a very active bassist, forming Material and playing on his near-neighbour Brian Eno’s groundbreaking ‘found sounds’ album collaboration with David Byrne, My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. Along with Eno and producer Martin Bisi, in 1979 Laswell founded BC Studio (first named OAO Studio) in the Gowanus area of Brooklyn, where the latter became effectively the in-house producer of Celluloid Records, the label responsible for a run of key records ranging from post-punk to hip-hop by artists such as Alan Vega, Fab 5 Freddy and Futura 2000.

“I remember the AutoTec tape machine was really old,” Laswell recalls. “When you started it up, it was like starting up an old car. It took a minute to get going. The board was a 16-channel Soundcraft console which was mostly used for monitoring live concerts. Later on we sold that console to [legendary New York club] CBGB and I think it might now be in one of those weird rock museums.”

Soon, other musicians from further afield were drawn to the cross-pollinated sounds that Laswell was producing in Brooklyn, not least Herbie Hancock. Together in 1983 the pair made the platinum-selling album Future Shock, with its electro-funk single ‘Rockit’.

Laswell remembers that before the release of the album, however, “Herbie was in trouble. They had been just doing kind of cheesy synth funk fusion stuff and it wasn’t selling and he was in debt with Columbia. It felt like we were gonna do something experimental. I did two songs and took the tapes to California and Herbie played on it, which took like an hour-and-a-half, and then I mixed it very quickly, in another hour-and-a-half. And we had no real idea what it was.”

The producer vividly recalls the moment that he realised he had a hit on his hands with ‘Rockit’, the track that would establish him as a major producer. “I was with the DJ [Grand Mixer] D.ST and we left the studio to go to the airport. We were driving on the highway and there’s all these stores that sell loudspeakers and stereo components. So we stopped and went in one and we said we wanted to hear some speakers. The guy was playing some record like Kansas or something. We said, ‘No no we don’t listen to that kind of stuff... play this,’ and we gave him the mix of ‘Rockit’. He put in on and played it at massive volume and it sounded good, very unusual and something different. And when the tape stopped, we turned around and there was like 10 or 20 kids from South Central and they were just looking at us like, What the fuck was that? [laughs]. And then D.ST looked at me and said, ‘Whoops, I think this is a hit record.’”

Cast Changes

In preparing for what would become the fifth studio album by PiL, John Lydon, living in Los Angeles, had begun writing and rehearsing new material in the basement of his house in Venice Beach with a young pair of musicians, keyboard player Jebin Bruni and guitarist Mark Schulz. “We had a tiny little drum machine, nothing great,” Lydon says. “But for me it’s always like that. The basics of an idea is good enough to get yourself into the studio, and then all those things will fall in place.”

Meanwhile, in New York, in doing his own pre-production for the project, Laswell had pulled together a band involving drummer Tony Williams (Miles Davis) and guitarist Nicky Skopelitis (Material), with himself playing bass. At The Power Station in New York, the trio cut the backing tracks for what was to become ‘FFF’, ‘Home’ and ‘Rise’. “John was coming to New York with his band,” says Laswell. “But a few days before that I made a decision that I would hire musicians and prepare music. So without any production meeting or plan I hired Tony and Nicky, and we mapped out a structure for three pieces. Then we cut them live in The Power Station with [engineer] Jason Corsaro who was at the time the beast of drum sounds. That’s the guy who kind of defined the ’80s.”

Corsaro set Williams up at the bottom of The Power Station’s elevator shaft, both close- and distance-miking the kit to create the distinctive drum sound on ‘Rise’ in particular: Shure SM58 on the snare, Sennheiser MD 421s on the toms and Neumann U47 FETs for the ambience. “Myself and Nicky played in the control room,” says Laswell, “and everything was a first take. We were using the Fairlight computer as a kind of click track, and on the piece that became ‘Rise’, Tony dropped a beat and we went back and dropped in this one beat. Otherwise I thought it was cool to be able to say everything was a first take.”

In terms of his own setup, at the time Laswell was using a Wal bass through an Ampeg SVT, blending the sound of the amp with a DI: “I got the idea of the Wal from some of the Eno records, ‘cause Percy Jones used one. It wasn’t a heavy bass, like a rock bass. It was more of a fluid sound and it was a fretless so for phrasing it helped just to elongate the feel of things.”

The control room in The Power Station’s Studio C, now part of Avatar Studios. Photo: Fin Costello/RedfernsLaswell had also hired former Cream drummer and notorious wildman Ginger Baker for the sessions, who arrived at The Power Station on the same day as Lydon, Bruni and Schulz flew in from Los Angeles. The producer set them up with Baker and another bassist, Malachi Favors, from progressive jazz outfit the Art Ensemble Of Chicago. “I hired him because I really liked his name,” Laswell laughs. “Nobody knew who the hell he was and he didn’t know what he was doing. But he just played these simple pulses to get the track cut. And we put the [other] guys in the back and when we heard how they played...”

The control room in The Power Station’s Studio C, now part of Avatar Studios. Photo: Fin Costello/RedfernsLaswell had also hired former Cream drummer and notorious wildman Ginger Baker for the sessions, who arrived at The Power Station on the same day as Lydon, Bruni and Schulz flew in from Los Angeles. The producer set them up with Baker and another bassist, Malachi Favors, from progressive jazz outfit the Art Ensemble Of Chicago. “I hired him because I really liked his name,” Laswell laughs. “Nobody knew who the hell he was and he didn’t know what he was doing. But he just played these simple pulses to get the track cut. And we put the [other] guys in the back and when we heard how they played...”

Very quickly into this session it became apparent there was a problem. “It was difficult,” says Lydon, “because the band I had in LA, they were very, very young chaps, and they couldn’t cope with the pressure of the New York studio. The whole thing tore them up really, and it was panicky fingers on strings, and time was of the essence. I think we’d given ourselves something like three weeks to make the whole album.

“The Power Station was a real thrill and, y’know, fair play to my young band, I had fears of it myself,” he admits. “It was very, very scientifically advanced. And y’know if not awe-inspiring, definitely awesome... dude. And it was a bit selfish of me to expect such young lads to be able to cope with that kind of in-at-the-deep-end. But then that’s how I’ve always treated myself. Everything I’ve ever done in music has been in-at-the-deep-end, sink or swim. And not many can keep up with that reckless sense of bravado.”

“So they did four pieces in that configuration with Ginger playing,” Laswell says, “and then that night we went to a bar and I explained to the kids, ‘This is serious and we have to make something great and we’re gonna have to let you guys go.’ They were probably hurt, but they were not ready.”

“I missed them severely, Schulz and Jebin,” says Lydon. “But I had to very, very quickly make a difficult decision of sending them home and replacing them, if I was ever gonna meet the obligation of the three week deadline. And so there it went.”

The drum and bass takes for the four tracks — ‘Fishing’, ‘Round’, ‘Bags’ and ‘Ease’ — were salvaged from the session and Lydon was faced with the prospect that for the first time he was to be making an album with outside session musicians. “It was a big, ‘Oh my God. What am I gonna do now?’” he says. “‘How are these ideas gonna transfer to these major players?’ And well, hello, they approached everything in the same way I did. And so there it is. There is no hierarchy in music. We’re all at it at the same level. Once you get the fear gone, everything else becomes great fun.”

Lydon perhaps unsurprisingly bonded with the fiery and unpredictable Baker. “I love him very much,” he says. “I really do. He’s a real person. My kind of bloke, y’know. Great fun in the studio. The amount of drum kits he destroyed was amazing. I think that was the biggest part of the budget [laughs].”

Melting Pot

From here the sessions moved through various New York studios for overdubbing, including Quadrasonic and RPM. Lydon admits that when it came to studio environments, he was at the time still quite wary of them. “Too many buttons, and every one of them has a winking light,” he says. “It can drive you nuts. But I mean I’ve learnt my way around a mixing desk over the years, so it doesn’t carry the same fears.”

Steve Vai, at the time the guitarist in American heavy metal band Alcatrazz, recorded his parts at the Jimi Hendrix-founded Electric Lady Studios. Vai’s invitation to join the sessions pointed to the fact that Lydon and Laswell wanted to push the PiL sound in a more heavy rock direction. “If anything, The Who Live At Leeds was my ambition,” says Lydon with a chuckle. “Bill had a very, very great record collection. Listen, if ever you wanna bond with me, have a roomful of vinyl and I’m in and straight into it. And actually that’s how we got to Steve Vai. I heard [Alcatrazz] and I went, ‘Ooh yeah, that’s alright, innit.’ We found records that we liked together and that gave us a shape to it.”

“I even remember telling John, ‘I only listen to metal,’ which is not true,” laughs Laswell. “But honestly I would go back and reference the huge metal records of the day, just for sonic comparisons. I was pretty conscious that we were dangerously close to some metal references. But there’s references to Greek music and Turkish music in some of the jangling parts.”

When Vai contributed his parts at Electric Lady, Laswell tried to influence the guitarist’s playing for Album by letting him hear more exotic styles of music. “We used Steve for the most part for solos and decorative kind of things,” says the producer. “So before he would play a solo, I would say, ‘Here, quickly listen to this.’ And I would play him, like, North African trance music for five minutes, or Indian music or Irish stuff. And it totally took him into another space. So when he soloed, it wasn’t the normal ‘here’s the big rock solo’. We didn’t really discuss the direction. We just played him those things to make sure it wasn’t your sort of standard rock guitar thing. ‘Cause even though I was moving probably close to metal, I was conscious not to do clichéd rock stuff.”

Laswell cites Vai’s guitar solo on Album’s atmospheric and thunderous closing track ‘Ease’ as evidence of where the stylistic clash between different musical worlds really paid off. “It’s a really long guitar solo,” he says. “It’s pretty self indulgent, considering it’s a John Lydon record, but it somehow worked. With Ginger playing, it’s not fusion, it’s not really metal, it’s more tribal kind of sounding, so it made sense.”

Elsewhere the electric violin of Shankar and the Fairlight textures of Ryuichi Sakamoto further coloured the sound to push it away from rock. “Sakamoto played very minimal on a few songs, playing kind of weird Oriental sounds,” says Laswell. “Nothing too graphic, nothing that really jumps out. And on [‘Ease’] he wrote an intro that sounds like Balinese music. So he’s present, but in a very subtle, almost ambient kind of way.”

Shankar’s percussive and drone violin parts were to prove subtly mesmerising on ‘Rise’. “We sort of referenced this idea of drones from the Indian music and the Irish fiddle music,” says Laswell. “Back in those days we amped things almost all the time, so there was probably an amplifier involved but at the end of the day you always favoured the DI, just for clean.”

“Oh, gorgeous tones,” says Lydon of Shankar’s contributions. “I love tones. It’s what I wanted with PiL in the first place. Just loads of inflections sort of buried in the background, so when you close your eyes those inflections will creep out and spur all kinds of delicious thoughts. Shankar was just marvellous. An eye opener. I knew his stuff, but I didn’t think he’d be quite in this mould. It completely worked and it made ‘Rise’ stunning. ‘Rise’ became a tour de force on that album.”

Vocals

Built around a rolling groove inspired by South African music, with its heavy drum sound, references to Irish and Indian tones, and Lydon’s compellingly manic vocal, Rise was a highly unusual pop song. Additionally, its message of anti-violence was a potent one. “Well, it was a song of rebellion,” says Lydon. “But also one against Nelson-Mandela-as-a-superhero, ‘cause I knew the other side of that. And I have an absolute hatred for people that resort to violence. I think we can solve the world’s problems with passive resistance. Y’know, you can put down your gun and think about this in another way.”

For the most part, Lydon worked out and sang his vocal parts at the microphone at RPM Studios. “Which is what I usually do,” he says. “I’ve got a headful of confusions, so I’ve always got ideas running.” The singer admits though that given the high bar set by the backing tracks, he felt pressure when it came to performing over them. “Yeah of course I did. I mean having to adjust to the idea of laying down the parts of the track first before the vocal... that was very, very difficult for me to get round. I didn’t like that at all. I never liked that with the Sex Pistols.”

Given the characteristic intensity of Lydon’s vocal performances, the challenge as always was to capture them before he exhausted himself. “I rev myself up and usually my first or second or third performance is the best,” he says. “It doesn’t usually change beyond there except gets rougher. ‘Cause I put so much energy into it. As with Never Mind The Bollocks, I wanted the words to come over like sharp knife cuts. Every single word well pronounced and deliberately in their place.”

“He had a notebook full of lyrics and it was fairly easy for him to chop up the lyrics and customise them to the tracks,” says Laswell. “He might record some ideas and then we would move them. Those days there wasn’t a lot of technology where you could sample. But you could take the vocal on a two-track tape and fly it back into the place where you wanted it to be. Most of the engineers from those days were assistants to the old engineers who had to do that stuff all the time.”

One of the other key features of ‘Rise’ was the backing vocals of Bernard Fowler (then of Material, now of the Rolling Stones), who taught Lydon on the sessions how to sustain longer notes. “Ah yes, Bernard was great,” Lydon remembers. “Bernard taught me vocal techniques that were simplistic, but for me were very challenging at the time. Just to get the harmonies right on Rise. It was an approach that I hadn’t involved myself with and I’ve got to say ever since then I became more and more involved in my craft as a singer.

One of the other key features of ‘Rise’ was the backing vocals of Bernard Fowler (then of Material, now of the Rolling Stones), who taught Lydon on the sessions how to sustain longer notes. “Ah yes, Bernard was great,” Lydon remembers. “Bernard taught me vocal techniques that were simplistic, but for me were very challenging at the time. Just to get the harmonies right on Rise. It was an approach that I hadn’t involved myself with and I’ve got to say ever since then I became more and more involved in my craft as a singer.

“It’s Bernard that set me off there. I never credited myself with being capable of doing that. I’d be my worst own enemy going, ‘Nah nah never.’ And I suppose this all goes back to my Roy Orbison record collection. Knowing I weren’t ever gonna sound like that. So I dismissed that capability and I shouldn’t have.”

Folk Music

For mixing, the project returned to The Power Station where Album was completed in Studio C using the facility’s SSL E-series desk. “It was because I wanted to do it with Jason [Corsaro],” says Laswell. “That was the room that he worked in and he was the most comfortable there. The pieces were not complicated. They were fairly easy to balance. ‘Rise’ was laid out perfectly and very simple. If you look at it, it’s really minimal drumming, simple bass line, chords that just follow the bass line and some random elements. It’s really not complicated music.”

Lydon also favoured keeping mix time to a minimum. “For me actually,” he says, “I prefer monitor mixes than going into a proper full-on mix. I like it just to sound as live as it possibly can. Once you start putting too much technology into it, the sound tends to become woolly and I don’t like that. I’m much more in the spiteful region [laughs]. Sonically...”

When Album was released in January 1986, in cover artwork that copied the generic ‘home brand’ packaging of products from the American supermarket chain Ralphs, the sleeve purposely didn’t list the credits of the session players involved. “If you list all those names,” Laswell insists, “that’s all they’re gonna talk about is the names, not the music.

“I wanted it to be as generic as possible,” says Lydon, “so the album wasn’t like, I dunno, a Band Aid with Geldof and a list of celebrities. I wanted it to be judged song for song.”

But while Album fared well in many territories, Lydon was dropped by his US label Elektra a week after it was released in America. “I lost the label, but so what?” he says.

“It was weird,” says Laswell. “As soon as it came out, I was in Europe a lot, touring with different people and everywhere I went, a club or a bar or a restaurant or a store, everybody was playing it. It was pretty big in Japan as well. I wasn’t monitoring what it was doing in the States ‘cause I was in Europe and I really felt the impact of it there.

“Y’know, those days and even worse now, the music business, it’s full of idiots and no one has any vision or intuition. It could be that we spent a lot of money too...”

Ultimately, though, ‘Rise’ has endured as the best-known PiL song and a track that continues to echo down through the decades.

“There’s a hookiness about the phrasing,” says Laswell. “The simple beat and the bass moving like that, and his chorus and the energy of what he puts into the verses. It’s an unusual hybrid of things but it doesn’t feel misplaced. It’s like a children’s song or something — things you end up hearing over and over in your head. It’s not complicated. It’s more like folk music in a way.”“It’s very folksy,” Lydon agrees, “and it’s very emotional. I suppose that’s the first time I really went into that kind of deep empathy with my fellow human beings, rather than like growling and being angst-ridden [laughs]. I turned anger into an energy.”