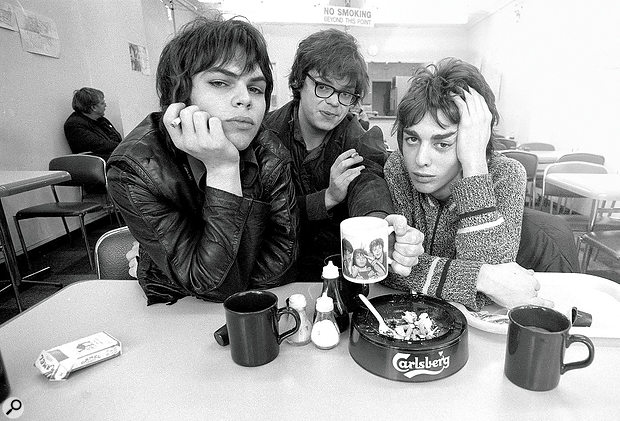

Supergrass. Left to right: Gaz Coombes, Mick Quinn and Danny Goffey.

Supergrass. Left to right: Gaz Coombes, Mick Quinn and Danny Goffey.

When producer Sam Williams discovered Supergrass, he knew he had to capture the band's infectious energy on tape.

In the crowded field of mid-'90s Britpop bands, Supergrass stood out. For a start, they were surprisingly young — singer Gaz Coombes was only 18 when they released their 1994 debut single, 'Caught By The Fuzz'. They were also in possession of a strong, boyish retro rock–band look and a different set of influences from their peers: Ziggy Stardust–era Bowie, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop.

But it's for their UK number two single of 1995, the irrepressibly bouncy 'Alright', that Supergrass are best remembered. In the song's video, their image was frozen forever as a Monkees-styled trio capering around on bikes and in a bed on wheels rolling along a beach, as Coombes sang a cheeky lyric about peak teenage delinquency: smoking fags, sleeping around, crashing a car in a field.

However, at the time, the success of 'Alright' was both a blessing and a curse for the band — Gaz Coombes (vocals/guitar), Mick Quinn (bass/vocals) and Danny Goffey (drums). It made their singer in particular a reluctant household face in that summer of 1995. "When 'Alright' went mental, we were in America," Coombes remembered in an interview with this writer four years later. "We got back and suddenly every fucker was recognising you. I never wanted to be a rock star. I just wanted to be in a band."

However, at the time, the success of 'Alright' was both a blessing and a curse for the band — Gaz Coombes (vocals/guitar), Mick Quinn (bass/vocals) and Danny Goffey (drums). It made their singer in particular a reluctant household face in that summer of 1995. "When 'Alright' went mental, we were in America," Coombes remembered in an interview with this writer four years later. "We got back and suddenly every fucker was recognising you. I never wanted to be a rock star. I just wanted to be in a band."

Almost 10 years after they split — and in the wake of Gaz Coombes enjoying a successful and critically-acclaimed solo career — Supergrass have re–formed. 2020 will see them back on tour, in support of a new career retrospective box set, The Strange Ones. Producer Sam Williams, who discovered the band and oversaw the making of their debut album I Should Coco, clearly remembers the day that he first encountered the trio in the street in Oxford in 1993.

"I was in a music shop and I came out and saw the boys standing on the pavement," he says. "It was one of those classic, surreal moments. I'd grown up with strong references to early Beatles and the Monkees and the cartoon kind of culture of larger-than-life '60s-looking bands. They didn't look like anything that you'd seen in real life for a long, long time. Danny was wearing a blue velvet suit with red Bowie hair and Gaz had the kind of Neil Young sideburns.

"The feeling was that it was just an immediate, magnetic attraction. Something in me just went, 'I don't know who that is. But I know that's a band and I know I'm going to produce them.'"

First Impressions

As a musician and producer, Sam Williams shared many reference points with the young members of Supergrass, but by this stage in his career, he had gained much more experience in the music industry. As the son of Len Williams, founder of the London Guitar School, and the brother of guitarist John Williams — a member of classical rock band Sky and also a soloist, whose rendition of 'Cavatina' famously became the theme from The Deer Hunter and a worldwide hit in 1978 — Sam Williams had been in and out of recording studios since he was a teenager.

Growing up playing bass, sax, clarinet, piano, drums and then becoming a singer, Williams had joined his first band at 11 and, by 16, had played bass on 'International Language', the debut single by Richard Strange, formerly of proto-punk band Doctors Of Madness. "They were interviewing him on Radio 1 when the single came out," Williams remembers, "and he was saying, 'Oh yeah, I got this schoolboy called Sam Williams to play bass.' And I was thinking, 'Well, look, if this is possible, then anything is possible.'"

Living in Cornwall by this point (where his father had relocated to found a monkey sanctuary), Sam Williams began to visit his local recording studio, Sawmills. At 18, driven to become a producer, arranger and artist, he was employed by Sawmills as an assistant and moved into the remote, residential facility.

"It's in a place called Fowey on the southwest coast of Cornwall," he explains, "and only accessible by boat or by walking down a railway line. I moved into one of the cabins that was part of the residential thing. Sawmills was just a stunningly beautiful place. A complete sanctuary as well, because obviously it was quite remote. It was like my rock and roll university."

At Sawmills, Williams was trained in old school analogue engineering and to-tape recording. "The guy that owned Sawmills at that point, Simon Fraser, was a fantastic mentor and teacher of a lot of recording techniques," he says. "I quickly got a feel for mixing and rigging up a lot of tape delays. I also got a taste for editing, because a lot of what I wanted to do wasn't easily doable or possible on conventional tape recording. So, we were into the land of click tracks and two–inch tape, but I'd be chopping up two–inch tape to get the results that I wanted that would be closer to the way that we would sequence and loop now."

Obviously, for an engineer, taking a blade to a reel of two-inch tape during a session required a lot of nerve and confidence. "I tell you what, man, it was really scary," Williams laughs. "Even on a basic multitrack edit where you wanted verses and choruses from two or three takes, you'd have a lot of pieces of tape hanging around in the studio over different bits of furniture, waiting to be assembled. And if anybody walked in and said something, it could disrupt your concentration and you could be in hell. Some of that did happen on a little bit of editing in that period of the first Supergrass record."

By the time Williams met Supergrass, he was already a veteran of countless sessions at Sawmills and the frontman of his own band, the Mystics, who'd signed to Fontana Records. "Those were the recordings that I initially played to Supergrass when I met the boys," he recalls. "Just as a kind of calling card of... 'Well, this is what I've been doing.' To say, 'Look, this is how it'll sound if I produce and if we go to Sawmills.'"

At the time, comically, and almost like the Beatles in Help!, the three members of Supergrass were living virtually door–to–door to one another in a set of cottages in the village of Wheatley in Oxfordshire. Sam Williams first saw and heard them play in a local pub. "I was blown away," he enthuses, "because it was super tight and super hard and very visceral and incredibly connective. Danny's drumming was drawn from a lot of different things — Mitch Mitchell, Keith Moon, and from Charlie Watts for the groove-orientated thing as well. A very creative player, a really great feel player. But intense energy.

"They were playing very fast, so it didn't take them long to play eight songs. They had elements of the Buzzcocks and they had elements of the Pistols a little bit with the guitar sound. But again, none of it in particular in terms of an homage or a pastiche. And it was incredibly concise songwriting, a bit like the speed at which the material was delivered."

Williams first offered to help quickly nail down demos of the band's songs, recording them playing live on a Fostex Portastudio at Danny Goffey's cottage, after randomly placing microphones around the tiny room. "Literally what I call Lazy Miking," the producer laughs, "where you throw a mic on the floor. We were just capturing. I think we may have overdubbed some vocals.

"They would play in a room where you could just get them and me in, and they'd play at full volume. I thought, 'This is a really good indication as to how this record should sound and feel.' So, we used the four-track recordings to get to a place where we had a pretty comprehensive sketch of pre-production for six tracks. We had a good synopsis, if you like."

One of the six songs they demoed together was 'Alright', in its original, scrappy form, built around pumping, staccato piano chords. "That was done on a very out-of-tune piano at Danny's cottage," Williams remembers. "We'd done everything on a four-track format that we didn't care about, but that was good enough to make choices and decisions about the arrangements. To get a good sketch of everything down and an overview of the material that we wanted to cut."

Sawmills

There have got to be worse places to record an album; Sawmills on the banks of the River Fowey.In the spring of 1994, Sam Williams and Supergrass first travelled down to Sawmills for a five-day session agreed as part of a production deal with the studio's owners. "We took the boat with the gear in it down the river and they just loved the place," says Williams. "I could see they got it and it was the right environment for them. It wasn't going to be overwhelming or over-spec in any way. It was just right... the feeling of containment and kind of like a little bit of naughty isolation."

There have got to be worse places to record an album; Sawmills on the banks of the River Fowey.In the spring of 1994, Sam Williams and Supergrass first travelled down to Sawmills for a five-day session agreed as part of a production deal with the studio's owners. "We took the boat with the gear in it down the river and they just loved the place," says Williams. "I could see they got it and it was the right environment for them. It wasn't going to be overwhelming or over-spec in any way. It was just right... the feeling of containment and kind of like a little bit of naughty isolation."

Together there the team began working with Sawmills' in-house engineer, John Cornfield. "My approach as a producer was to enable the making of a record the way I imagined Sam Phillips would work at Sun, or the way I imagined the culture would be at Stax or Motown," Williams explains. "It was an in-house feeling about it, especially in terms of collaborating.

"I was working with John Cornfield, who is a world-class engineer," he stresses. "And coming at it from a different point of view that was ideal as an old school team. It allowed me to have a relationship with the band that was fundamentally based on playing, arranging, having fun, and getting the energetic lines of the production right."

True to his original idea, Sam Williams wanted to recreate the intensely concentrated sound of Supergrass' four–track demos. "When I was in the cottages recording that immense racket in a small space," he says, "I knew how I needed to record I Should Coco, which was with the amps mainly in the same room. Because that's all the band had known.

"I also wanted some element of controlled bleed, even into drum mics. Which is not ideal, if you're looking for a kind of perfect, separated sound. But I knew it would help in that way that it had with some of the Spector things. I could hear the element of bleed that I liked."

Williams' approach had the band playing while wearing headphones, but at the same time still able to hear and feel the familiar blasts of sound from the drums and amps. "If you close a band off too soon when they're young and give them headphones," he argues, "they lose physical contact with the acoustic elements of the velocity and the transients and the way that they make contact with an instrument. John and I had a little chat about: 'OK, we're gonna do it this way.' We did spread [the amps out] a little bit as the record progressed, but not massively. The energy of the band was in their eye contact and volume."

The picturesque location of Sawmills certainly helped to create the right mood for the sessions, too. "It was not a big live room," says Williams. "A nice-sized room, but with an immensely cool, creative playing vibe. The windows looked out onto a completely isolated creek with swans swimming around on it, and with the woods on the other side.

"If a take was finished or half-finished, we'd get into canoes and row over to the other side of the creek and have a listen to a playback through the windows of the studio. Have a little smoke, go back again, do another take. It was that kind of atmosphere. They loved it."