The three albums Mike Thorne produced for Wire showed that there was much, much more to punk than met the eye.

Decade after decade since their formation in 1976, London quartet Wire have continued to prove to be hugely influential. While still very much a going concern (in 2020 they released their 17th studio album Mind Hive), it’s their initial three albums — ’77’s Pink Flag, ’78’s Chairs Missing and ’79’s 154 — that have cemented their status as a classic band whose art rock sounds have echoed down the years.

In the early ’80s, the likes of the Jam and REM (who covered Wire’s ‘Strange’ on their 1987 album Document) sang the band’s praises and were inspired by their minimalist, angular shapes. Later, in the ’90s, Damon Albarn riffed on the chant of Wire’s ‘I Am The Fly’ (from Chairs Missing) to create Blur’s ‘Girls And Boys’, while Elastica virtually sampled the beat and riff of Pink Flag’s ‘Three Girl Rhumba’ for their track ‘Connection’ (prompting an out‑of‑court settlement). More recently, the sound of Wire can be heard in current bands such as Shame and Squid.

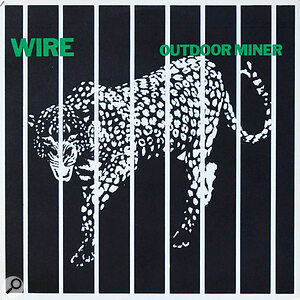

‘Outdoor Miner’, from Chairs Missing, was the closest the band ever came to a hit, when the chiming, melodic single reached Number 51 in January 1979. The track stalled when the band’s label EMI were accused by the British Market Research Bureau of suspicious chart‑rigging activity involving the heavy buying of the single in chart return shops. Hit hyping was a common practise at the time. “But of course,” Wire producer Mike Thorne laughs today, “EMI would be the one to get caught.”

‘Outdoor Miner’, from Chairs Missing, was the closest the band ever came to a hit, when the chiming, melodic single reached Number 51 in January 1979. The track stalled when the band’s label EMI were accused by the British Market Research Bureau of suspicious chart‑rigging activity involving the heavy buying of the single in chart return shops. Hit hyping was a common practise at the time. “But of course,” Wire producer Mike Thorne laughs today, “EMI would be the one to get caught.”

This minor controversy wasn’t to ever diminish the timeless appeal of ‘Outdoor Miner’, which remains a staple on alternative radio. In 2004, an entire tribute album — A Houseguest’s Wish: Translations Of Wire’s ‘Outdoor Miner’ — was dedicated to the track, featuring 19 versions of the song by the likes of Lush and Flying Saucer Attack.

Perhaps the secret of Wire’s long‑lasting influence lies in the fact that — in their original line‑up of Colin Newman (vocals/guitar), Graham Lewis (bass/vocals), Bruce Gilbert (guitar) and Robert Grey (drums) — they always stood apart from the pack. While they emerged during the era of punk, Wire seemed to instantly transcend it.

“Well, Wire weren’t just punk rockers,” stresses Mike Thorne. “They took the energy and the aggression of punk and channelled it into their own language.”

Plunged In

As a producer, Mike Thorne has a long list of diverse credits to his name, including Soft Cell, John Cale, Laurie Anderson, Blur and Roger Daltrey. Back in 1970, he started his career as a tape operator at De Lane Lea Studios in London, thrown into the deep end working on sessions with Fleetwood Mac and Deep Purple.

“You just got plunged in,” he remembers now. “I showed up on the Monday morning at 10 o’clock and there was nobody there yet. I thought, ‘Well, I guess this is the business,’ and people started rolling in. By Wednesday afternoon, I was on a Fleetwood Mac session. Those Fleetwood Mac and Deep Purple sessions, you just did your minor job, making tea a lot of the time, and just paid attention. I got fired after a year. But that was enough to get me on my way.”

Thorne’s next move was into A&R, bringing the Sex Pistols to EMI Records for their brief, one‑single association with the label with ‘Anarchy In The UK’ in 1976.

“When I arrived at EMI, I didn’t know that being an A&R man involved hanging around late‑night clubs and talking to other people,” says Thorne. “I thought it involved going out and seeing as many bands as possible, which wasn’t really the way that people did it. So I got out and about, and I picked up the phone when Malcolm McLaren called. Nobody else wanted to take the call.

“It turned out that the Pistols were playing the 100 Club in Oxford Street. So off I went, I liked what I saw, and I talked my boss into going up to Doncaster to see them and he liked what he saw. Counter to the way people were reacting to the shock‑horror press, we thought they were a decent bunch of people and made very different music that we liked.”

Thorne meanwhile started working as a record producer when he oversaw the live punk compilation album, The Roxy London WC2, recorded at the legendary club venue using the Virgin mobile studio.

“I got wind of the fact that The Roxy guys were thinking of putting a four‑track in the back of the club and doing a recording and putting it out,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘This is a rather good idea, but it could use more resources.’ So, I got on the phone, went down and saw them and then we did the whole works. And the rest is a very nice piece of history.”

The bands featured on the album included Buzzcocks, X‑Ray Spex and, fatefully, Wire. “Nothing stood out about them to start with,” says Thorne, “because that was one of their very first gigs. But eventually, it was just the strength of the songs and the strength of the delivery, which is what you look for in anybody really.”

The producer took it upon himself to get Wire signed to EMI and offered to record demos with the band in the company’s eight‑track basement studio at their headquarters in London’s Manchester Square. “It had a small old EMI desk with eight group outputs — it was enough, it didn’t need to go any further than that — and a one‑inch tape machine.

“That was a nice little place. It had a couple of permanent engineers, but they were perfectly happy for me to go in on a Saturday afternoon, which is what I did. It was a very good way of getting close to the artists. I did that with Kate Bush too. It was just me and the band or the artist. You got a lot closer. You got to understand each other a lot better that way. And also, they could see that I knew where the on/off switch was (laughs). So, there was more confidence on both sides.”

Wire: Bruce Gilbert, Robert Gotobed, Graham Lewis and Colin Newman.Photo: Annette Green

Wire: Bruce Gilbert, Robert Gotobed, Graham Lewis and Colin Newman.Photo: Annette Green

Pink Flag

Work began soon after on Wire’s debut album Pink Flag, produced by Mike Thorne at Advision Studios in central London. Comprised of 21 tracks clocking in at a mere 36 minutes, it was a punchy and inventive first offering. Some songs were shorter than a minute, with the jerky, propulsive ‘Field Day For The Sundays’ lasting a mere 28 seconds.

“Yep,” Thorne laughs. “We had a different approach. It wasn’t exactly going in, thinking, ‘What should we do next?’ We had a meeting at my flat in South London before we got started, and we worked out the running order. So we went in and played it in the running order and then picked up the pieces. Obviously, we redid quite a lot.”

Throughout the ’70s, Advision had been the scene of key recordings by David Bowie (The Man Who Sold The World) and Elton John (Caribou). By 1977, its control room housed a Studer A80 24‑track two‑inch tape machine and Quad‑Eight console.

“I liked the engineer at Advision, Paul Hardiman,” Thorne remembers, “and I liked the vibe of the place. I did have quite a look around London before settling on Advision. And of course, I settled there for quite a few years after that.”

One of the other big draws for Thorne to Advision was its large live room, since he was after capturing a more open drum sound on Robert Grey’s kit than was fashionable at the time.

One of the other big draws for Thorne to Advision was its large live room, since he was after capturing a more open drum sound on Robert Grey’s kit than was fashionable at the time. “The live room was one of the prerequisites,” says the producer, “because I learned very quickly — which was an attitude that was catching on at the time — that it was good to put the drummer in a big room.

“In the older days, the drummer would be in his drum booth. And that, of course, made for a very dry sound. But that was the style of the times. Everybody wanted this sort of analytical sound much more about colour and texture rather than a big noise. But I was looking for the racket, and I got it.

“We used the room very much because that just gives you the raucousness. Whereas a lot of people would just use the reverb, we used the sound of the room itself. And having the drummer out in the room meant that Robert was getting a response from the walls. That’s much more encouraging than being plonked in a little dead space.”

Elsewhere, Wire’s crunchy guitar sounds were created using Music Man 65 Watt combo amps, each miked with an Electro‑Voice RE20 and Neumann U87. “We used the 65 Watt version because it’s the easiest to overdrive,” says Thorne. “On that album Colin played my Gibson Les Paul Pro, which is the custom but with single‑coil pickups. It was very, very, very powerful and very, very sort of defined.

“Sometimes we would have a mic out in the room just to get some ambience around the amp. And it was quite tricky, the mic placement, just to get the right amount of reinforcement and colour. But once we had the mics in position on the amp, we wouldn’t move them for the whole sessions.”

Additionally important to Wire’s guitar sounds were the effects pedals, including the MXR Distortion+ and the Electro‑Harmonix Big Muff.

“MXR and Electro‑Harmonix were just starting to release all sorts of interesting noises,” Thorne says. “And I went for all of those. I wound up with a huge amount of effects pedals, of all shapes and sizes. Because I was always concerned to get the guitar sound at the amp, rather than processing it later, or, y’know, adding effects in the studio.

“It was much more satisfying plugging in the funny pedals and then getting the sound there. And of course, it gave the guitarist a much better lead because he would be hearing the eventual sound and playing to it. Rather than just, y’know, some nondescript sound and then shoving a flanger on later.”

The energy on Pink Flag was captured by tracking the songs live. “Yes, completely live,” says Thorne, “and sometimes we kept the vocals Colin recorded using an 87. He was in the drum booth, so he had his own little scene in there.”

Wire later admitted that while nailing down the tracks, “tempers were often frayed”. The producer similarly remembers the atmosphere at the sessions being tense. “I would often hear a clattering of drumsticks and it was Robert either getting frustrated with not being able to get what he was going for, or he’d thrown his drumsticks at Graham’s head and missed (laughs). They were intense sessions, as you can imagine from the music.”

Wire’s crunchy guitar sounds were created using Music Man 65 Watt combo amps, each miked with an Electro‑Voice RE20 and Neumann U87.

Overdubs were kept to a minimum, the main exceptions being the layers of overdriven guitars on the ‘Pink Flag’ title track, and what Colin Newman described as his “chord solo” on ‘Lowdown’. “Most of the time we double‑tracked the guitar,” Thorne says, “or maybe replaced the original. The first album was quite minimal, but it’s a very full sound. So, we didn’t have to take it very far.”

‘Strange’, meanwhile, featured barely recognisable flute overdubs played by Kate Lukas. “No, well, she’s playing flutter‑tongue, the ‘frrrr’ sort of sound,” the producer explains. “She was actually my flute teacher and she said it was one of the most difficult sessions she had ever done. Because it was scored in tone clusters, which is a semitone apart, and maybe there were 10 different lines going, it’s not too rewarding when you’re playing it.

“It sounds pretty good at the end of it all. But that’s why it doesn’t sound like a solo flute, because it isn’t. There’s probably some delay on it. But the effect is really all those closely spaced flutes and her flutter tongue.”

The metallic clanking heard at the end of ‘Strange’ was in fact Thorne playing a percussive part on a fire escape door. “Yes,” he laughs. “The band thought I’d lost it. I just said, ‘What it needs at the end of this track is somebody banging away. Somebody trying to get out.’ So, I just went and started banging with a drum stick on the side of the fire escape door. And as often happens when you just do something spontaneously, it works.”

Chairs Missing

By May 1978, when Wire and Mike Thorne returned to Advision to make the band’s second album, Chairs Missing, there was a mood for further sonic experimentation in the air. The result would be added atmospheric layers to the production, as the band members became more interested and involved in the recording process.

“Yeah, they’d also become very, very capable,” Thorne points out. “And so off we went. They said, ‘We want keyboards on this album.’ I said, ‘Well, who’s going to play them?’ They said, ‘You.’ I said, ‘Alright.’ (laughs).”

Their first shared keyboard experiment was a failed one, however, when they tried to “prepare” a piano for a never‑to‑be‑released song called ‘Underwater Experiences’.

“It was a very, very standard thing to do to prepare a piano. John Cage started that off really. He was the first person to put bits and pieces and wedges between the strings. And so I did a bit of that. But a lot of it was just scrubbing the strings with a drumstick. And in some cases, holding keys down with tape, so that you could scrub the strings and you’d hear this racket, but you’d get a chord that would emerge out of it all at the end of the scrubbing. As you can imagine, it was a little difficult to manipulate.”

Mike Thorne playing keyboard with Wire, 1978.

Mike Thorne playing keyboard with Wire, 1978.

More successful were the overdubs that Thorne added to Chairs Missing using the small, but choice collection of keyboards and synths he had at the time: namely an RMI Electra‑piano (often fed through a distortion pedal or overdriven amp), an EMS Synthi AKS and an Oberheim Eight Voice (providing, amongst other things, the arpeggio part on ‘Another The Letter’).

On one track, ‘Sand In My Joints’, Thorne fed both Colin Newman and Bruce Gilbert’s guitars through the Synthi AKS to create a fractured, synthetic dual solo. “I learned early on that you can get some really good things by shoving guitar through a synthesizer and just using the filters,” he says. “But the ring modulator on the Synthi AKS requires two inputs to make any sound at all.

On one track, ‘Sand In My Joints’, Thorne fed both Colin Newman and Bruce Gilbert’s guitars through the Synthi AKS to create a fractured, synthetic dual solo.

“You can do that all sorts of ways. But in this case, it was two guitars going into it, and you’d only get a sound out of it when they both played. And then of course, it was a very contorted sound. And that’s the results that you hear.”

‘Outdoor Miner’, meanwhile, was incredibly simple and direct. A mere 1 minute and 44 seconds in length, it was driven by a very tight and dry, new‑wave‑style drum sound and lightly distorted or chorused guitar sounds. “It was very straightforward,” says Thorne. “It was a nice tune, and they played it, and there it was. We didn’t have to muck around with it at all, really.”

But while ‘Outdoor Miner’ was considered a commercial and possibly radio‑friendly song, it was deemed too short, and so EMI asked Thorne to take another look at the track. “Yes, it was the only time I’ve ever been asked to make a single longer,” he laughs.

Thorne copied the 24‑track master tape onto a second reel and edited in a verse section over which he played a piano solo, plus a third chorus including expanded backing vocals. In the final mix, however, it became clear that the piano would have to carry on throughout the track, or else its sudden absence would be felt.

“It left big yawning gaps, which is why the piano got extended,” says Thorne. “But it turned out pretty well in the end.”

The other standout song on Chairs Missing was ‘I Am The Fly’, the most sonically altered track on the album. Along with its spidery guitars and overdriven, harmonised claps, its main feature was Colin Newman’s rhythm guitar part heavily treated with an MXR Flanger.

“It’s all the knobs turned all the way up,” Thorne laughs. “Colin had used that flanger in the demo studio. He’d borrowed somebody else’s. So I actually went out on the morning of the album session and bought one in Charing Cross Road.”

Even though its production was much more involved, Thorne doesn’t remember that the mixing of Chairs Missing was any more tricky than Pink Flag. “We didn’t have much trouble on the mixing, because I was always a stickler for recording,” he says. “You would be able to put the 24‑track on and you’d sort of hear the track without any fiddling around.

“It had become a habit of mine just to record as often as possible with the effects that you wanted on the finished thing, rather than saying, ‘We’ll put a flange on this in the mix.’ And that was a very good way to do it, because everybody else would hear shades of the eventual sound. And they’d respond to it, and you’d get even more interesting sounds.”

154

When it came to the recording of Mike Thorne’s third and final album with Wire, 154, the quartet had done a lot more touring and were much more experienced as a live unit. In fact, its title came from the exact number of gigs the group had played up until this point.

To the producer’s ears, they sounded like a different band. “Yeah, better,” he says. “They just walked in and played. It was great. And 154 did coincide with the number of gigs that they’d done at that moment.

“In the control room, before it was properly named, everybody was puzzling about what to call this third album. And Graham said, ‘Why not just the number of gigs we’ve done? Like 154, or something.’ And it turned out that they had actually done 154 gigs. They pulled that number out of thin air.”

If 154 was generally a less obviously melodic and more post‑punk experimental album, it reflected the fact that all four members of Wire were far more studio‑savvy and keen to push their ideas.

If 154 was generally a less obviously melodic and more post‑punk experimental album, it reflected the fact that all four members of Wire were far more studio‑savvy and keen to push their ideas. “The difference was that all the band were coming forward,” says Thorne. “They had technology and they could use it and they did. They were much more active in the production side of things. And this was good. It just took it all to another level.”

One highlight of 154 was ‘Map Ref 41 Degrees N 93 Degrees W’, which took the propulsive, strummy approach of ‘Outdoor Miner’ one step further. “Piling up the vocals was fun,” Thorne remembers. “It was just such an exercise in vocals.” Similarly, on the tense and brooding ‘Indirect Enquiries’, vocal overdubs of the menacing closing hook (“You’ve been defaced”) were layered up in various forms — what Thorne describes as “the deepest, growling sounds and the highest‑pitched chipmunks”.

Meanwhile, the producer’s keyboard‑playing had a starring role in ‘The 15th’, with his synth washes and percussive stabs. “It was often a struggle for me to get the keyboard parts done,” he admits. “Because at that point, I didn’t practice too much. A year or two later, I would deliberately practice. Do the five finger exercises and go into a session ready. But back then I couldn’t move my fingers fast enough most of the time (laughs).”

Elsewhere, ‘A Mutual Friend’ employed vocal tape loop chords featuring the voice of Hilly Kristal, owner of New York punk club CBGB. Thorne had recently been over in Manhattan producing the self‑titled 1978 debut album by CBGB regulars, the Shirts, and had taken the opportunity to record Kristal’s voice.

“Hilly had actually in previous years sung on the stage of Radio City Music Hall, cause he started off as a performer,” the producer explains. “He had a genuine bass voice. So on the Shirts session, I just took 10 minutes and recorded him going ‘awww’ and then strung them all together in a loop. And so I could then play different notes of Hilly and I would fade them in and out depending on what chord I wanted to hear.”

Another guest, appearing on ‘A Touching Display’, was electric viola player Tim Souster. “He was in Karlheinz Stockhausen’s band, Intermodulation,” say Thorne. “Never underdoing anything, I set him up with all three Music Man amps that we had and split his viola feed. I stood him in the middle of all this lot and fiddled with the sound, so that each amp sounded a little bit different. I might even have had some pitch‑shifting.

“But anyway, it was a glorious place to stand and play. And he went and nailed it immediately. He built up the chords, doing separate improvisations, but he sort of knew where he was going, and that’s the huge chord at the end.”

Ex Lion Tamer

In the studio during the recording of 154, it was clear that the tensions between the members of Wire were growing. “Well, there were a couple of factions,” says Thorne. “There was Colin, and to a certain extent, Robert, and then Graham and Bruce.” The producer further admits that, with himself included, “it was five very large personalities. And after a while there wasn’t really enough room in one room for everybody.”

Mike Thorne today.Perhaps some of this frustration can be heard in one particular track on 154, ‘Once Is Enough’, where bassist Graham Lewis can be heard hammering away on pieces of scrap metal. “That was so funny,” says Thorne. “I don’t think that was to do with frustration. It was just Graham said, ‘I’ve got this idea. I just want to run around the room and hit things. So we found all sorts of bits and pieces. But it was not too intense because we could hardly stop laughing.”

Mike Thorne today.Perhaps some of this frustration can be heard in one particular track on 154, ‘Once Is Enough’, where bassist Graham Lewis can be heard hammering away on pieces of scrap metal. “That was so funny,” says Thorne. “I don’t think that was to do with frustration. It was just Graham said, ‘I’ve got this idea. I just want to run around the room and hit things. So we found all sorts of bits and pieces. But it was not too intense because we could hardly stop laughing.”

During the mixing of 154, however, Thorne told the band he’d decided it was to be the last album he made with them.

“I resigned just because it all seemed to be getting a little bit too personal and intense,” he explains. “I want to have fun in the studio. I don’t need to deal with personal conflicts. So one day during the mixing, when they arrived, I just said, ‘I want to call it quits.’ But, y’know, everybody was on the same page.”

Shortly after the release of 154, Wire broke up, partly as a result of their surplus of conflicting ideas. Eight years later, in 1987, though, they regrouped, releasing the more electronic‑leaning The Ideal Copy. Guitarist Bruce Gilbert was to finally quit the band in 2004, being replaced by Matthew Simms, who remains in the line‑up to this day.

Wire had actually written a letter to Mike Thorne back in 1986 to ask him if he’d be keen to work on The Ideal Copy, but he hadn’t responded to them in time.

“In the ’80s, I was working like a maniac,” he says. “I could barely sit down. Y’know, when they wrote to me, I don’t even know which country I was in. The letter got to me. I’ve still got it framed on the wall. It was a very nice note. But I was just working so hard that I could barely stop and think.”

Wire’s erstwhile producer is meanwhile happy to see that the band remain operational and forward‑looking. “I don’t think they could ever not be,” he points out. “Good luck to them.”

As to why those first three Wire albums continue to be so widely loved and influential, Mike Thorne partly credits the technological advances of the late 1970s.

“Well, we were very lucky,” he states. “That was a time when all these new machines were coming in. Lots of new attitudes to playing. We jumped in on them. And that’s reflected in the excitement in the albums.”