Harrison’s MixBus is intended to offer the ‘look and feel’ as well as the sound of a large-format mixing console.

Harrison’s MixBus is intended to offer the ‘look and feel’ as well as the sound of a large-format mixing console.

Harrison’s MixBus promises the sound and user experience of a large-format console, at approximately one-thousandth the price!

Harrison have built their reputation around the construction of high-end, large-format mixing consoles. These are used in some of the best studios around the world, and many classic recordings have been made through them. In more recent years, they have integrated digital technology into their hardware consoles and, in 2009, they added the next logic step in the product line: MixBus, a consumer-level digital audio workstation.

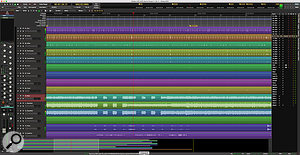

The Editor screen provides a fairly conventional timeline-based view of your project, with tools for all the usual audio and MIDI editing. MixBus wasn’t conceived as a standard DAW, though. The design and implementation was built very much around Harrison’s console-based background. From day one, MixBus was intended to provide the same recording and mixing experience as their large-format consoles and, as importantly, the same ‘analogue’ sound. Harrison have added to its feature set in subsequent versions and, by the time SOS reviewed version 3 in September 2015, it had become a very capable DAW. However, the fundamental design elements of console workflow and console sound remain at the heart of the design. This has won MixBus a number of admirers, including many who record in another DAW but use MixBus as their mix platform of choice exactly because of the workflow and sonics. MixBus is also unusual in being available for Linux as well as Mac OS and Windows.

The Editor screen provides a fairly conventional timeline-based view of your project, with tools for all the usual audio and MIDI editing. MixBus wasn’t conceived as a standard DAW, though. The design and implementation was built very much around Harrison’s console-based background. From day one, MixBus was intended to provide the same recording and mixing experience as their large-format consoles and, as importantly, the same ‘analogue’ sound. Harrison have added to its feature set in subsequent versions and, by the time SOS reviewed version 3 in September 2015, it had become a very capable DAW. However, the fundamental design elements of console workflow and console sound remain at the heart of the design. This has won MixBus a number of admirers, including many who record in another DAW but use MixBus as their mix platform of choice exactly because of the workflow and sonics. MixBus is also unusual in being available for Linux as well as Mac OS and Windows.

Harrison have now delivered MixBus 4, with an array of new features. Does this mean the program is now ready to relinquish its specialised status and move into the DAW mainstream?

Big & Bigger

MixBus 4 comes in two versions: MixBus and MixBus 32C. Both offer unlimited numbers of audio tracks and MIDI tracks, and plug-in support constrained only by your host computer’s resources. Both also offer third-party plug-in support, video playback, ripple editing, LTC/SMPTE sync and the usual array of audio and MIDI editing tools required to construct your projects. Both also offer the console workflow and sound that is at the heart of the design. There are two key differences between them, both related to how ‘big’ your virtual mixing console is. First, while MixBus offers three-band sweepable EQ and a high-pass filter on each channel, MixBus 32C’s EQ takes its design from Harrison’s 32-series hardware mixers. It therefore offers four-band EQ, with the top band switchable between shelving and peaking, and both high- and low-pass filters. Second, while MixBus offers eight stereo mix buses, MixBus 32C increases this to 12, providing greater flexibility.

It’s also worth noting that, in both versions, all the processing options available within the channel strip are ‘pre-allocated’ host resources. If your project is currently running smoothly, enabling additional EQ or compressor instances within the MixBus mixer will not suddenly push you over the CPU cliff. Harrison do note, however, that their analogue console emulation perhaps means MixBus is more demanding of CPU resources than some other DAWs.

That said, the user interface is designed very much with a conventional studio workflow in mind, where tracking and mixing are separate stages of the project. If you follow this approach, then once all the parts are captured, you can set a larger audio buffer size to give your CPU more scope to do its thing.

Split Screens

For this review, I was working with MixBus 32C but, in terms of basic operation, the two versions are very similar. Although some features and settings are tucked away in pop-up windows and dialogue boxes, the bulk of your time is divided between the Editor and Mixer screens. You can toggle between these using the main menus, key commands or the two buttons located at the top right of the window.

The topmost strip of both windows is where we find the most obvious reworking of the MixBus interface for version 4. This now contains a much more compact transport section, plus access to key controls for overdubbing and recording modes, along with the time display/tempo information. The right-hand side of this strip holds a new feature: the ‘mini-timeline’.![]() The new mini-timeline view makes project navigation much easier, especially in the Mixer window. This is very useful for project navigation, particularly when in the Mixer window. If you populate your project with suitable Location Markers in the Editor window, these appear in the mini-timeline, making it easy to hop between song sections. Some might find the new transport section a little too compact, but as I suspect experienced users will be using either key commands or an external controller for most transport functions, and there is also a dedicated Transport menu, I think it’s worthwhile to save the space for the new features.

The new mini-timeline view makes project navigation much easier, especially in the Mixer window. This is very useful for project navigation, particularly when in the Mixer window. If you populate your project with suitable Location Markers in the Editor window, these appear in the mini-timeline, making it easy to hop between song sections. Some might find the new transport section a little too compact, but as I suspect experienced users will be using either key commands or an external controller for most transport functions, and there is also a dedicated Transport menu, I think it’s worthwhile to save the space for the new features.

Included among some minor cosmetic adjustments within the Mixer is a new feature added to all the mix busses: a stereo width control located just below the VU meters. As well as the Drive and dynamics options, each of the mix bus channels now features a stereo width control. Also note the K-14 meter on the master channel to encourage you keep plenty of dynamic range in your final mix. While this doesn’t offer stereo expansion, it does allow you to reduce the stereo spread on individual buses, and this might be useful for keeping your low-frequency sounds focussed in the centre of the stereo image, or if you want to narrow an effect return.

As well as the Drive and dynamics options, each of the mix bus channels now features a stereo width control. Also note the K-14 meter on the master channel to encourage you keep plenty of dynamic range in your final mix. While this doesn’t offer stereo expansion, it does allow you to reduce the stereo spread on individual buses, and this might be useful for keeping your low-frequency sounds focussed in the centre of the stereo image, or if you want to narrow an effect return.

Fading Fast

The new VCA fader system offers unlimited faders, automation and very easy channel assignment options.

The new VCA fader system offers unlimited faders, automation and very easy channel assignment options.

Perhaps the most significant new feature of version 4 is the addition of VCA faders. Again, the approach adopted is transferred from Harrison’s own hardware console VCA implementation. An unlimited number of VCA faders can be added, each offering level, mute and solo control over any ‘slave’ channels. VCA faders can be fully automated, and automation data is handled elegantly even when channels are dropped from a VCA fader group.

Assigning channels to a VCA fader is simply a matter of selecting the required channels, right-clicking on the appropriate VCA fader channel, and selecting Assign Selected Channels. Usefully, individual channels can be assigned to multiple VCA faders.

VCA faders share another very useful new workflow feature with the mix bus channels: Spill buttons. MixBus 4 adds the very useful Switcher panel at the top of each channel strip. These have nothing to do with microphone spill elimination between channels: if you click on one of these Spill buttons on a VCA fader or mix bus channel, the main mixer hides all channels apart from those linked with that VCA fader or mix bus. This is an excellent addition and makes it incredibly easy to focus temporarily on, for example, just your drum channels or vocal channels; hit the Spill button again and all the hidden tracks reappear.

MixBus 4 adds the very useful Switcher panel at the top of each channel strip. These have nothing to do with microphone spill elimination between channels: if you click on one of these Spill buttons on a VCA fader or mix bus channel, the main mixer hides all channels apart from those linked with that VCA fader or mix bus. This is an excellent addition and makes it incredibly easy to focus temporarily on, for example, just your drum channels or vocal channels; hit the Spill button again and all the hidden tracks reappear.

To check VCA assignments, you can simply click on the new Switcher zone located at the top of any channel. The new tempo mapping options mean that you can release your musicians from the tyranny of the click track, yet still make full use of the MixBus MIDI sequencing features. A VCA label appears here if the channel is assigned, and the Switcher panel, which temporarily replaces the insert effects display, shows which VCA fader(s) the channel is linked to.

The new tempo mapping options mean that you can release your musicians from the tyranny of the click track, yet still make full use of the MixBus MIDI sequencing features. A VCA label appears here if the channel is assigned, and the Switcher panel, which temporarily replaces the insert effects display, shows which VCA fader(s) the channel is linked to.

This panel holds other useful settings too, including input assignment. With In active, the channel receives audio or MIDI from its assigned physical input, while Disk means the channel plays back audio or MIDI from the timeline within the Editor window. Shift-clicking opens the Switcher on all channels, while Command+Shift-clicking on the In or Disk buttons toggles the status for all channels in the project. This is very useful when you are moving from a multitrack recording session to the mixing phase.

Also new for version 4 is tempo mapping.  MixBus 4 has improved support for virtual instruments with multiple output channels such as Kontakt or, as shown here, Superior Drummer and, if required, will automatically create the necessary mixer channels within your project.Music-to-picture composers will find good use for these new features, but perhaps the most obvious application is to create a tempo map for a source recording made without a click track. The Tempo track allows you to enter tempo markers along the timeline to create tempo changes, which can be instant or ramped. However, you can also click and drag upon the bar/beat grid within the Tempo track to line it up with obvious transients in your click-free audio. The process does require a little bit of hands-on work to set up the initial tempo map but, once done, the grid will sit correctly on your audio, and any MIDI instruments added as overdubs, such as a virtual drummer, will follow the natural tempo variations in the original recording. Having tried it with a couple of ‘free-form’ recordings, I can say the process actually works pretty well and, while it requires more manual input than the equivalent methods in some other DAWs, it is a very welcome addition to the MixBus feature set.

MixBus 4 has improved support for virtual instruments with multiple output channels such as Kontakt or, as shown here, Superior Drummer and, if required, will automatically create the necessary mixer channels within your project.Music-to-picture composers will find good use for these new features, but perhaps the most obvious application is to create a tempo map for a source recording made without a click track. The Tempo track allows you to enter tempo markers along the timeline to create tempo changes, which can be instant or ramped. However, you can also click and drag upon the bar/beat grid within the Tempo track to line it up with obvious transients in your click-free audio. The process does require a little bit of hands-on work to set up the initial tempo map but, once done, the grid will sit correctly on your audio, and any MIDI instruments added as overdubs, such as a virtual drummer, will follow the natural tempo variations in the original recording. Having tried it with a couple of ‘free-form’ recordings, I can say the process actually works pretty well and, while it requires more manual input than the equivalent methods in some other DAWs, it is a very welcome addition to the MixBus feature set.

Turn On, Plug In, Rock Out

The MixBus Mixer does, of course, offer console-style — and very musical — EQ and dynamics on every channel, so users will be able to perform routine mixing tasks without additional equalisers or compressors. However, you will need to budget for additional options such as reverb/delay and, as described in the ‘Beyond The Basics’ box, Harrison have their own range of plug-ins available if you don’t already have a suitable plug-in collection.

New in version 4, however, are a bundled GM synth, the FluidSynth SoundFont player (there are lots of SoundFont libraries available online), plus two acoustic drum kit instruments called Red Zeppelin and Black Pearl. The former is a rock kit with a nice dollop of room ambience, while the latter is drier. Both sound pretty good but, aside from being able to tweak the sounds via the MixBus channel strip controls or other processing plug-ins, this isn’t really a replacement for EZ Drummer and the like, as you can’t swap kit pieces in and out; what you hear is what you get. That said, as one of the further new features in MixBus 4 is better support for virtual instruments with multiple outputs, once each kit piece is assigned to its own mixer channel, you can get suitably creative with sound shaping.

As well as Harrison’s default LV2 format, MixBus 3 supported VST plug-ins under Windows and AU under OS X. Usefully, the OS X support now also includes VST, and you can mix and match formats within a single session. The multi-channel output support also seems to work well with third-party instruments. For example, I had no problems getting NI’s Kontakt and Toontrack’s Superior Drummer 3 configured and, for the latter, it was rather nice to see my MixBus session instantly populated with 20-plus additional channel strips for each of my SD3 microphones. The new Spill buttons on the mix bus and VCA fader channels bring a further workflow enhancement to the mixing experience within MixBus, allowing you to easily focus on specific subsets of the main channels.

The new Spill buttons on the mix bus and VCA fader channels bring a further workflow enhancement to the mixing experience within MixBus, allowing you to easily focus on specific subsets of the main channels.

Support for third-party plug-ins is still perhaps a relatively new element in the MixBus paradigm, and to their credit, Harrison admit that MixBus might not be 100 percent compatible with every plug-in out there. However, aside from the occasional graphical issue (for example, when resizing the floating window for Kontakt), I had no real problems with any of the third-party plug-ins I tried during the review period. Plug-ins from NI, Toontrack, iZotope, Waves and Celemony, for example, were all hosted happily within MixBus 32C v4 on my test system.

Worked Over

For obvious reasons, this review has focussed on the new features in MixBus 4 but, of course, these simply add to what was already a well-specified recording, editing and mixing environment. MixBus still lacks a few MIDI bells and whistles compared to some other DAWs, but the MIDI feature set has all the essential tools. Add your preferred selection of third-party instruments and additional effects, and MixBus is a seriously powerful music production environment. But does it deliver on the promise of standing out for its large-format console workflow and sonics?

I can’t say I’ve done exhaustive (or even scientific) listening tests, but I couldn’t resist the temptation to try mixing a couple of audio-only multitrack projects in both MixBus and Cubase Pro 9, my usual DAW of choice. In both cases, I confined myself to MixBus’ channel-based EQ and dynamics and the stock plug-ins that make up Cubase’s Channel Strip. With different toolsets available on the two platforms, it was inevitable that the mixes would sound different; but, having tried as well as I could to match the EQ and dynamics settings in both mixing environments, I’m not sure those differences were of the ‘chalk and cheese’ variety. That said, I really like what the channel EQ and dynamics can do in MixBus and I particularly like what the Drive (saturation) controls on the mix bus and master output channels do to the sound. It’s a subtle effect but very pleasing on the ear in a way I couldn’t quite seem to recreate with Cubase’s saturation options, although the latter are perhaps more flexible.

However, despite my considerable familiarity with Cubase, what particularly impressed me about MixBus was how quickly my mix came together. My usual approach starts with levels, pan, EQ and dynamics, and having these all present and ready to go on each channel strip makes for a very streamlined process. In this sense, MixBus is very like working on a hardware console with a fixed channel structure. Yes, you can pop the audio out of a channel to additional plug-ins, as you would with external hardware on a physical console, but the bulk of what you need is already there under your hands (or mouse!). As a consequence, you spend less time on distractions, and a mix can come together very quickly.

The bottom line here is that the MixBus mixer is, ergonomically, a joy to use. The 32C version offers enough audio routing options to cope with complex projects and the new VCA faders simply add to what’s already a great mixing platform. Whichever way you ears might jump on the question of sonics, from a mixing workflow perspective, MixBus is a class act.

Bus Trip

Harrison have introduced enough new features in MixBus 4 to make this a considerable step forwards. The ‘new’ highlights for me are the VCA faders and the improved plug-in support, particularly under OS X, but the real standout feature remains its ‘console in software’ design. I’m not sure a typical review period is long enough to form a well-founded opinion about whether MixBus really does sound ‘more analogue’ than other DAWs, although I’m aware that there are plenty of experienced industry professionals who are of that opinion. MixBus does sound very good, though, and those channel-strip EQ and dynamics work very well. Where I’m happier to jump off the fence is in the workflow aspect of the ‘console in software’ design. There is a beauty and ergonomic elegance to this that is incredibly attractive and makes MixBus very impressive as a dedicated mixing platform.

At just $79 for the standard edition (and with an upgrade path to the 32C version if required), MixBus also offers an attractive point of entry. Is it therefore ready to go mainstream? Well, as Harrison have also introduced a free-to-try, fully functional (it inserts occasional low-level noise), downloadable demo, you can experiment for yourself to discover just how this ‘analogue’ software console sounds and operates. For anyone looking to streamline their mix process, this is an experiment I would most heartily recommend.

Alternatives

We are not short of options when it comes to DAWs. However, MixBus’ unique selling point is the emulated workflow and sonics of a large-format console and, from that perspective, I’m not sure there really is a direct competitor. Something like Steinberg’s Channel Strip perhaps gets close in concept to the MixBus mixer channels but, despite perhaps having more features, it doesn’t offer quite the same ergonomic advantages.

Arguably the closest experience to MixBus is currently provided by some boutique third-party plug-ins. For example, SSL mixer channel emulations such as those offered by Waves or UA might provide similar features, but handling lots of plug-in instances in a busy mix would be nowhere near as efficient as working with the MixBus mixer. Softube’s Console One aims to capture both the ergonomic and the sonic advantages of a large-format console, but is tied to its own hardware controller, while the sonic aspects alone might be replicated by something like Waves’ NLS or the recently released Brainworx bx_console E and bx_console G. However, at their full price, each of these costs the same as MixBus 32C itself.

Beyond The Basics

Harrison have their own range of plug-ins that you can add to MixBus, including the Gverb and 3D Triple Delay that form the Essentials bundle. If you wish to supplement your processing options within MixBus, Harrison have their own range of add-on LV2 plug-ins available. Their $79 Essentials bundle provides delay and reverb, while the $219 Character bundle offers plug-ins specifically aimed at drums, bass and vocal processing. There are also individual boutique-style options including various advanced EQs, gates and dynamic processors. These are all pretty good, but some individual plug-ins are actually more expensive than the standard version of MixBus 4 itself, which may well deter those on a tight budget.

Harrison have their own range of plug-ins that you can add to MixBus, including the Gverb and 3D Triple Delay that form the Essentials bundle. If you wish to supplement your processing options within MixBus, Harrison have their own range of add-on LV2 plug-ins available. Their $79 Essentials bundle provides delay and reverb, while the $219 Character bundle offers plug-ins specifically aimed at drums, bass and vocal processing. There are also individual boutique-style options including various advanced EQs, gates and dynamic processors. These are all pretty good, but some individual plug-ins are actually more expensive than the standard version of MixBus 4 itself, which may well deter those on a tight budget.

Script Writing

One intriguing new feature in MixBus 4 is Lua Scripting, which is likely to appeal to a particular niche of the user base. It is, in essence, a macro language that enables users to create and edit simple scripts to automate specific chains of commands. Lua Scripts can be assigned to buttons that appear top right within the upper transport/mini-timeline control strip, for easy access. My review copy of MixBus didn’t ship with any example scripts but the potential of the technology is obvious. This is something that I suspect could be hugely powerful once the user community starts to build and share scripts.

Pros

- The ‘console emulation’ workflow makes for an efficient mixing process that is a pleasure to use.

- Whether it captures the sound of an analogue console or not, MixBus does sound very good indeed.

- New features such as VCA faders, better plug-in support and tempo mapping are very welcome.

- The standard edition of MixBus is excellent value for money.

Cons

- Apart from the excellent Mixer EQ and dynamics, the stock plug-in collection is pretty modest compared to most DAWs.

- MIDI feature set is perhaps best described as solid rather than spectacular.

Summary

Sonic benefits aside, the console-style approach to mixing provided by MixBus is both very attractive and very efficient. Harrison have enhanced that experience even further in version 4, with the VCA fader support alone reason enough to upgrade.

information

MixBus 4 $79; MixBux 4 32C $299; upgrades from v3 $39 and $149 respectively.

MixBus 4 $79; MixBux 4 32C $299; upgrades from v3 $39 and $149 respectively.

Test Spec

Harrison MixBus 32C v4.1.

Apple iMac with 3.5GHz Intel Core i7 CPU and 32GB RAM, running OS 10.12.5, with Soundcraft Signature 12MTK.