Prash ‘Engine‑Earz’ Mistry in his new studio space at London’s Tileyard. The room is fully equipped for both stereo and Atmos mixing and mastering.

Prash ‘Engine‑Earz’ Mistry in his new studio space at London’s Tileyard. The room is fully equipped for both stereo and Atmos mixing and mastering.

High‑end outboard is an essential part of Prash Mistry’s mixing and mastering setup — as heard on Kali Uchis’ hit album Red Moon In Venus.

“The new studio is absolutely phenomenal to work in! When Lavar and I sat down to design it, we wanted to integrate the absolute best of analogue outboard and A‑D and D‑A conversion, with the most futuristic approach to workflow. I can stereo mix, stereo master and Atmos mix here seamlessly. It’s gorgeous. I’ve finally got the room I always wanted!”

Prash ‘Engine‑Earz’ Mistry moved into his brand‑new studio a week before this interview took place, and is obviously still almost beside himself with enthusiasm. The spacious, skylit room, which he designed with colleague Lavar Bullard, is located in the Tileyard studio complex in central London, which hosts over 130 studios in total and is one of the largest creative communities in the UK.

Mistry’s new Forwa3DStudios certainly seems to warrant the excitement, with a large number of unusual touches that make it stand out. To start with, the studio contains the best equipment money can buy, including Kii Audio Three BXT monitors, a full Amphion Atmos system, ATC 100As with Velodyne sub, an extensive collection of mixing and mastering outboard, eight‑channel SSL G‑series and 12‑channel Neve 81 sidecars, and 16 channels of summing each from Dangerous and Chandler.

Most impressive is the way this enormous amount of equipment has been seamlessly integrated, courtesy of PreSonus Studio One’s Pipeline function, a 384‑point digitally controlled analogue Anatal XBay 512 patchbay, Merging Ravenna audio interfaces, and more. It’s all designed to allow Mistry to switch at the press of a button between stereo mixing, stereo mastering and Atmos mixing, the only wrinkle being the need to transfer stems from Studio One to Pro Tools for Atmos mixing.

The Anatal automated patchbay is key to Mistry’s ability to quickly create recallable hardware processing chains.

The Anatal automated patchbay is key to Mistry’s ability to quickly create recallable hardware processing chains.

The Engine Room

As a mixer and mastering engineer, Mistry has worked with the Prodigy, Jorja Smith, Wizkid, PartyNextDoor, SZA, Stormzy, Kid Cudi, Burna Boy, J. Balvin, Aloe Blacc, D4VD, Skepta, Megan Thee Stallion, St Vincent, MIA, H.E.R. and Aitch, to name a few. In 2018, he received his first Grammy nomination for Best Immersive Audio for his own album Symbol, released under the name Engine‑Earz Experiment. More recently, Mistry mixed Raye’s hit album My 21st Century Blues in Atmos with his colleague Lavar Bullard, who operates from their second Amphion‑equipped Atmos studio in Norwich. Mistry also works regularly with Columbian‑American singer Kali Uchis. For the singer’s second Grammy‑nominated album, 2020’s Sin Miedo (del Amor y Otros Demonios), he mixed all 11 songs in stereo and Atmos, including global smash ‘Telepatia’, and mastered two.

Uchis’ third album Red Moon In Venus was released this March and is already a big hit in the US. Mistry mixed nine songs, and stereo mastered and Atmos mixed all 15. Mistry’s work on this album, and the track ‘Fantasy’ in particular, is the focus of this Inside Track. He performed all the work in his previous studio, which was also at Tileyard, with mostly the same gear as in his new room.

Prash Mistry: I’ve used Cubase, Nuendo and Pro Tools, and we obviously love using Pro Tools for the Atmos stuff, but Studio One’s integration with outboard is far beyond everything else.

Pipeline At The Gates Of DAW

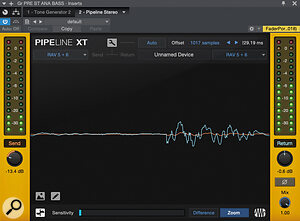

At the heart of Mistry’s mixing and mastering process is PreSonus’ Studio One DAW. “The reason I love Studio One and prefer it over other DAWs for stereo work is Pipeline XT,” he explains. “The Pipeline plug‑in offers a seamless way to get in and out of your DAW to your hardware. I’ve used Cubase, Nuendo and Pro Tools, and we obviously love using Pro Tools for the Atmos stuff, but Studio One’s integration with outboard is far beyond everything else. It’s incredible.

For Mistry, the killer feature of Studio One is its ability to seamlessly integrate hardware courtesy of the Pipeline XT plug‑in.“Pipeline automatically adjusts the delay compensation after pinging the signal chain, it can check phase and level, adjust wet and dry, and so on. It is phase accurate, sample perfect, and the recall is exact as well. It allows me to build whole outboard chains using the XBay and run them live in the session, without any delay, in the same way as I’d use an in‑the‑box aux channel with plug‑ins. Once I have the outboard the way I want it, I record it in the session, and mute the outboard aux channel, and carry on mixing. I can recall the aux channel at any point. The entire setup is just beautiful.

For Mistry, the killer feature of Studio One is its ability to seamlessly integrate hardware courtesy of the Pipeline XT plug‑in.“Pipeline automatically adjusts the delay compensation after pinging the signal chain, it can check phase and level, adjust wet and dry, and so on. It is phase accurate, sample perfect, and the recall is exact as well. It allows me to build whole outboard chains using the XBay and run them live in the session, without any delay, in the same way as I’d use an in‑the‑box aux channel with plug‑ins. Once I have the outboard the way I want it, I record it in the session, and mute the outboard aux channel, and carry on mixing. I can recall the aux channel at any point. The entire setup is just beautiful.

“I also use Studio One for mastering, and again, Pipeline XT makes it possible for me to engage my mastering outboard in the same way I use plug‑ins. My mastering rack consists of EQs like the EAR 825Q, Bettermaker, API 5500, Thermionic Culture The Kite, Oakfield Audio, and compressors like the Elysia Alpha, API 2500, Dangerous, Maselec MLA‑4, and Maselec MPL‑2 high‑frequency limiter, which works as a de‑esser. I also have Lavry AD24‑200 Savitr A‑D, Lavry Quintessance D‑A and Cranesong Solaris D‑A converters in my mastering console.

“In general, I love using Studio One because I find the workflow completely uninhibited. I’ve never hit a point where it can’t do what I want it to do. It’s extremely intuitive, and just really fun to use. If it stops being fun, I’ll look at something else, but I continue to look forward to coming to work and turning it on. I am still on version 4 due to the vast amounts of ongoing projects we have going on here. I am keen to move to version 6, though, and take advantage of all the new features.”

Trust In Analogue

The outboard racks at Engine‑Earz are stuffed with premium outboard, much of which was used on Prash Mistry’s mix of ‘Fantasy’.Mistry’s love of analogue, and the way he uses it in Studio One, routinely leads to enormous sessions — in the case of ‘Fantasy’, a whopping 359 tracks. “Like most engineers, I have every plug‑in you can imagine, and I sometimes mix in the box. If I’m working on a drill track, for example, there’s less added value in going to outboard, because the genre generally does not require it. It’s more of an in‑the‑box genre, and that’s the sound. However, if I want tone, dimension, depth and space, and I want to maintain phase coherence, analogue hardware still wins. There definitely is huge sonic value in going through analogue gear. It allows a degree of chaos in the mix, making sure things don’t sound the same as everyone working in their DAWs. There’s a randomness. It’s a matter of, as Quincy Jones said, ‘letting God inside the room’.

The outboard racks at Engine‑Earz are stuffed with premium outboard, much of which was used on Prash Mistry’s mix of ‘Fantasy’.Mistry’s love of analogue, and the way he uses it in Studio One, routinely leads to enormous sessions — in the case of ‘Fantasy’, a whopping 359 tracks. “Like most engineers, I have every plug‑in you can imagine, and I sometimes mix in the box. If I’m working on a drill track, for example, there’s less added value in going to outboard, because the genre generally does not require it. It’s more of an in‑the‑box genre, and that’s the sound. However, if I want tone, dimension, depth and space, and I want to maintain phase coherence, analogue hardware still wins. There definitely is huge sonic value in going through analogue gear. It allows a degree of chaos in the mix, making sure things don’t sound the same as everyone working in their DAWs. There’s a randomness. It’s a matter of, as Quincy Jones said, ‘letting God inside the room’.

“Some plug‑ins that model analogue gear sound great and absolutely capture the flavour of what they are modelling, but mess up phase coherence in the process. One well‑known brand in particular is a culprit. It is great that they ‘feel’ analogue, but if you cannot run a snare through it and trust that the transients remain punchy and match the same left and right, I cannot trust it. Whereas if I go through my outboard APIs, for example, they feel true to source unless there’s an actual problem with the unit. It’s the same with my Neve and SSL sidecars: the compression, gate, and EQ are all incredible solid.

“As the great Bob Ludwig once said: ‘Never turn your back on digital.’ There may be an aliasing issue, or improper dither, or some detail may not be coded right. Some plug‑ins can have five different revisions in the first week of release, and who knows which one they got right? For me, as a professional, that makes them very hard to trust. Whereas my hardware units, I know they work, I know they sound effing amazing, and I’m going to stick with them.”

Space & Groove

Mistry’s mixing and mastering work on Kali Uchis’ Red Moon In Venus album, and the song ‘Fantasy’ (ft. Don Toliver) in particular, is a good example of his approach. “On this album, Kali had a vision of wanting the vocals to be considerably louder than in your average pop record. That was the brief from the beginning. She wanted her vocals to be very upfront, and this involved giving her vocals plenty of space and depth. But because many of the tracks are dance songs as well, I also had to make sure that the groove, particularly the kick and the bass, were very present and equally important as the vocal. I then used a lot of width and space on the melodic elements, placing them as a framing around the drums, the bass and the vocals.

“‘Fantasy’ was a very important song to mix for me, because it has Kali’s partner, Don Toliver, on it. It is a genuine love song between them, they are very in love! So the song had to feel like a dance between a couple completely enamoured with each other. The emotion feels very genuine, and I had to make sure it really connected with them, and the listener. Most importantly, it had to feel right for Kali, because she really drove the vision for this project down to the finest detail. I’m doing everything I can to deliver that for her, down to the vocal effects, the way the beat feels, and so on.”

The accompanying screenshots show the entire PreSonus Studio One arrange page for Prash Mistry’s mix of ‘Fantasy’.

The accompanying screenshots show the entire PreSonus Studio One arrange page for Prash Mistry’s mix of ‘Fantasy’.

Download a ZIP file of Mixer and Arrange hi-res detailed screenshots from Prash Mistry's Studio One session for 'Fantasy'.

![]() inside-track0523-studio-one-fantasy-screens.zip

inside-track0523-studio-one-fantasy-screens.zip

Plain Colours

Mistry’s enormous session for ‘Fantasy’ (see https://sosm.ag/mistry) has a number of unusual aspects, both visually and structurally. “My sessions are extremely dull‑looking, because I don’t like to use many colours. I can’t listen properly with too many visual distractions. I struggled with that quite a lot, and then decided to limit the amount of colours I use.

“So grey are normal audio tracks, folder tracks are blue, turquoise are outboard aux channels and prints, wet mixed stems are in green, and occasionally I treat myself, and make updated vocal tracks that came in after I started mixing purple, and reference tracks red! You can see the green mixdown stems right at the top of the session: Lead Vox All, Kali Bvs, Don Bvs, Kick, All Drums, Snare, and so on. I print these stems when the mix is done, and I deliver them to the label, and drop them in my Atmos mix session.”

Another striking aspect of the ‘Fantasy’ session is the large number of aux channels, as they are called in Studio One. There are 33 vocal aux plug‑in effects channels alone, for example, as well as dozens of aux group channels that send to Mistry’s outboard via aux effects tracks, using the Pipeline plug‑in. The effected audio is in each case printed right above that, and a dry and muted copy of the same audio immediately above, as a fallback.

According to Mistry, all this is part of his mix template. “I have built my templates up over the years. They’re all mono‑compatible, and get updated when I find a new plug‑in I like. These aux channels are starting points, and I will tailor the effects to each part or project. I adapted a template for Kali’s album, and one for Aitch’s album, and so on.

“I have always loved working with vocal effects in particular, which is why I have such a large amount of aux channels for them. In my head I imagine a sphere of sonics coming out of the two speakers. Different combinations of different effects give me control over XYZ, ie. a way to move things around in the stereo field. For the vocal effects I have different types of rooms, different pre‑delay lengths, different types of reverbs, different types of echoes, delays, Eventides, and so on. Different combinations of each one can change the perception of where each vocal is placed in the stereo field.

“In addition to all the plug‑in aux channels, I also have inline group tracks that are sent to a group track and then Pipeline sends the audio to the XBay via the Merging Ravenna network to whatever outboard chain I have built. So in the ‘Fantasy’ track there’s an outboard effects section with the Eventide H9000, Bricasti M7, EMT 240 plate, Boss CE‑3000 Super Chorus and Klark Teknik DN780 reverb. I used these outboard effects on bass, different groups of synths, pads and vocals.”

Vocals

“First of all, as always when I do a mix, I asked producers P2J and Jahaan Sweet for wet and dry stems. I like starting where the producers left off, but I prefer not to see everyone’s plug‑in chains or their automation. I just want to be aware of where they’ve left off, where they were happiest, and then take it to the next level.

“Kali’s vocals had a very honest, less processed, natural sound, whereas Don’s vocal sounded more contemporary, almost trap‑influenced. His vocal was very forward, as if it was recorded with a Sony C800, whereas she sounded like she was recorded on a vintage Neumann U47, brilliantly tracked by Austen Jux‑Chandler. So I took a different approach to each of them to get them balanced and to make them feel like they are in the same song.

“In terms of outboard on Kali’s lead vocal I have the Bricasti M7 and my EMT 240 plate, and the Elysia Mpressor, the Stam SA‑2A, Pultec EQ‑1P, and my SSL G‑channel sidecar, going via an aux channel called Gr TT Mono. You could say that I use my SSL as an effects unit, for that Dr Dre punch and ’90s R&B sound. I find the way the compressor locks something in the stereo field right in front of your face invaluable. In the box I have the Massenburg MDWEQ5 EQ and the Sonnox Oxford Dynamic EQ. There’s also some transparent processing on individual words and phrases using gain and iZotope RX.

As well as numerous digital reverbs, Mistry owns an EMT 240 plate.“I had more in‑the‑box treatments on Don’s vocals than on Kali’s, because she is the lead artist, and I wanted to bring Don’s vocals in line with hers. The main treatment on Don’s voice comes from the McDSP APB Royal Mu, which adds some analogue drive, depth and warmth, and brought the sound of his voice closer to Kali’s. I also used the Oeksound Soothe, the UAD MDMWEQ, and sends to the EMT 140, Bricasti, EMT 240 and Soundtoys EchoBoy delays.

As well as numerous digital reverbs, Mistry owns an EMT 240 plate.“I had more in‑the‑box treatments on Don’s vocals than on Kali’s, because she is the lead artist, and I wanted to bring Don’s vocals in line with hers. The main treatment on Don’s voice comes from the McDSP APB Royal Mu, which adds some analogue drive, depth and warmth, and brought the sound of his voice closer to Kali’s. I also used the Oeksound Soothe, the UAD MDMWEQ, and sends to the EMT 140, Bricasti, EMT 240 and Soundtoys EchoBoy delays.

“The backing vocals were really important for Kali on this album. They are very big and very forward, so I did a fair amount in the box on them to make them sit right in the mix, using the Soothe 2, Tokyo Dawn TDR Limiter, Soundtoys PanMan and Oeksound Spiff. I also use the APB Royal Mu on Don’s backing vocals, and the FabFilter Pro‑Q 3, and the Soothe 2, plus tons of sends to my weird vocal busses.

“This is all before the backing vocals go through a rather luxurious analogue stereo backing vocal chain that I created in outboard. It consists of the EAR 825 EQ, which is rare tube mastering EQ, then the Crane Song Trakker compressor in clean opto mode, which gives it a beautiful smooth compression, not too jagged, really gently reacting to the transients and the flow of the vocal. You get a nice width as well if you unlink the compressors. Then they go through the Maselec MPL‑2, my mastering de‑esser, which sounds very natural and does not get in the way; and then into channels 7 and 8 on the SSL to give them that forward SSL ’80s sound.”

The McDSP APB Royal Mu compressor provided the main treatment on Don Toliver’s voice.

The McDSP APB Royal Mu compressor provided the main treatment on Don Toliver’s voice.

Drums

“The top drum folder contains a group of drum aux channels, like Altiverb Drums, Wide Drums, Drums Parallel, and so on. So, similar to with the vocals, I’m feeding my drums to these different aux channels to get different sounds and energies, in parallel, that I then mix in. There was already a certain feel on the original drums from P2J and Jahaan that I did not want to lose. So instead of processing on the main drums, I do parallel mixing.

UA’s Ocean Way Studios plug‑in helped soften the rimshot sound.“I sent the drums out to my outboard group aux channel, which has the API 2500, the Bettermaker limiter, and the SSL sidecar for that punch and snap. As always, I mixed that back in and printed it on the track above, and the original audio is muted above that. The outboard is for the overall feel, but I also have plug‑ins as inserts on individual drum elements, when I need to do very detailed work. Some of the plug‑ins I used are the UAD Massenburg EQ, which I love very much, Soothe, Spiff, FabFilter and Kirchhoff EQs.

UA’s Ocean Way Studios plug‑in helped soften the rimshot sound.“I sent the drums out to my outboard group aux channel, which has the API 2500, the Bettermaker limiter, and the SSL sidecar for that punch and snap. As always, I mixed that back in and printed it on the track above, and the original audio is muted above that. The outboard is for the overall feel, but I also have plug‑ins as inserts on individual drum elements, when I need to do very detailed work. Some of the plug‑ins I used are the UAD Massenburg EQ, which I love very much, Soothe, Spiff, FabFilter and Kirchhoff EQs.

“I also use the UAD Ocean Way plug‑in a lot on drums, to move things away from the virtual microphone. Many sampled sounds obviously were tracked very close‑up, and it does not benefit the listener to have the hi‑hat that close to your head. So I like to move them a bit further away, using the virtual room in Ocean Way. I did it with the rimshot in this session, which was really hard, and took away from the smoothness of the song. So I just backed it up a little bit. And finally, on All Drums I have the UAD Massenburg EQ, the Acustica Fire The Clip, the SoundRadix Pi Phase Interactions, and Spiff.”

Bass & Music

“The bass is a really big feature in this song. There’s an arpeggiated synth bass, and the main sub. I am a big believer in trying to make the bass as huge as possible. There are many different ways of doing that. Bass 01 is the main bass track, on which I have as inserts the Pulsar Mu compressor, the ReFuse Lowender creating a sub octave, the UAD Massenburg EQ, the Oxford Dynamics, the Pi, the UAD Empirical Labs, and more.

“There’s a send to a Distressor and then phase correction. There’s also a Widening bus. I’m using a flanger to create a sense of depth. There’s also an iZotope RX7 to clean things up. I am constantly de‑clicking so I can turn things up without getting distracted by artefacts.

“After that, I go to the outboard. I used my 1960s Lang outboard EQ, which has a huge amount of headroom for low end. The sub went through that, and it ended up sounding massive. And then a little bit of the Elysia Karacter and Elysia Xpressor. Most of the music tracks go to the outboard. There are not that many musical elements, but they have a lot of automation, to make sure that things are moving in the right place, and are dipping in and out on the right moments.”

The bass on ‘Fantasy’ was elevated by numerous hardware processors working in parallel, with mix automation used to vary the respective levels.

The bass on ‘Fantasy’ was elevated by numerous hardware processors working in parallel, with mix automation used to vary the respective levels.

Mastering

“I’ve been fascinated with mastering since I started producing. Because I was working on electronic music, I wanted the music to really banging on a live sound system, and a lot of that comes from mastering. When I was 16‑17, I used to go to a cutting room in London called Music House, and you had to queue up outside to get your dubplate cut, so you could play it at a rave. You’d go there to get your acetate cut, and there’d be a queue of DJs. I’d be waiting there for seven hours with my DAT, and then the guy listened to it, EQ’ed it a bit and cut my acetate. It cost me 50 quid and first time I listened to it at home, it sounded terrible! That was when I realised that there’s another stage that gives competitive sonics, and I wanted to learn how to do this. Mastering has been an obsession of mine ever since then, and as I was buying mix gear, I was also buying mastering gear. I was building up the sonics on the mix side and also thinking how I could deliver my mixes in a better way.

“Mastering for me is zooming out and looking at the whole project. This is the artist, this is who they are, this is where the song is going to sit, this is how loud it needs to be competitively, this is the emotion that needs to be communicated to the listener. Whereas when I’m mixing I am just focusing on one song, and I am going to make this song as good and captivating as I can make it, to get it to where the artist is 150 percent happy.

Mistry is both a mastering and a mixing engineer. This is his mastering console.

Mistry is both a mastering and a mixing engineer. This is his mastering console.

“Many artists are happy that I can master as well, because they like to keep their vision in one place. From an artist perspective, let’s say you finish your song, everything is amazing, and then someone at the label is telling you ‘Cool, but now let’s send it to another engineer, let’s take it all apart and put it back together again. And hopefully it is going to be better than it was before!’ That can be quite a traumatic experience for an artist who could already be in 15 rounds of changes so I try to be as compassionate as possible.

“Knowing that the same guy will be applying his ear and his understanding of the project to the mix and the mastering processes, and also the Atmos mix, gives artists peace of mind. This end‑to‑end type workflow saves artists and producers having to explain their vision to several different people and therefore saves time that can be spent on the project itself.

“I don’t have a problem with both mixing and mastering. I am quite self‑deprecating in my work, so I am able to look at my mixes with a fairly objective ear. I keep the mixing, mastering and Atmos stages entirely separate. I will export my mix, and then master, and we only ever do the Atmos after I have mastered. I have to draw the line at some point. Otherwise, you will never stop unpicking your session. Mastering should be a fresh look at the project. Which means that we should commit the mix, and move on to the next stage. For my mental health also, that is a good thing!

“The exceptions are genres like drill and EDM, where a lot of the time I already put a mastering chain on during the mix, because these tracks have to be delivered at such a loud level that you can’t get a perspective of the mix without the mastering chain. It means that I will work into clippers and limiters as I mix. Even then, I will take the limiter off at the end, bounce the pre‑master and then master that.

“Sometimes other engineers master my mixes, which I really enjoy as well. It can be very interesting to get someone else’s perspective on my mix. Or I get to master mixes by others. With Kali’s album, I mastered David Kim’s mixes. He’s a fantastic engineer who mixed five songs on the album. Because I had used so much outboard during my mixes, I mastered my songs in the box, but I mastered his songs out of the box, to balance them with the overall sonics of the album.

“Kali’s vision is so strong across all the songs, it was not hard to make them fit everything together seamlessly. She had a real grand vision that all the songs should actually flow into each other, like they would back in the day. The interludes were to be part of the track. If you go to Spotify there are no breaks, the album keeps flowing. Because of that everything sits well, and it was a real pleasure to mix as well as to master. I had a fantastic time on it.”

From Reading To The World

Prash Mistry’s success is the culmination of an early interest in music that began when he started playing piano at the age of six. His parents were part of the Ugandan Indian community that fled to the UK in 1972 when dictator Idi Amin ordered the expulsion of all Asians in the country. They eventually settled in Reading, where the young Mistry also learned to play tabla, harmonium, flute, drums and guitars.

However, Mistry’s older brother, Mitesh, had a Roland MC‑303 Groovebox that piqued his interest. “I got obsessed with electronic music. I ended up creating a live set with the Groovebox sequencer and another keyboard I had, and did my first club night when I was 14. We toured the UK after that and with some friends I created a band, and got into drum & bass. I ended up putting on lots of huge jungle and drum & bass raves from age 17 to 21.

“At 21, I started my own studio, and began producing artists. I got my first mixing desk, an Allen & Heath GS3000, a rack of samplers and outboard, and helped local artists to make records. When I was 27, I started my band Engine‑Earz, and we toured all over the world for a few years. I then started mixing.

“My first ‘official’ success was with Jorja Smith’s song ‘Blue Lights’ [2016]. I’ve mixed and mastered all her records to date, working closely with her label FAMM, and from there my career as a mix engineer just built. People kept calling me to mix their records, also because of the connections I’d built up as an artist, promoter, and producer. Today, I work in every genre, whether metal, rock, EDM, neo soul, R&B or reggae. Because hip‑hop/R&B is so dominant in the charts right now, my biggest projects seem to be from that genre.”