Italian band Måneskin were unlikely winners of the 2021 Eurovision Song Contest, but even that couldn’t prepare them for what came next. Mix engineer Alessandro Marcantoni tells the story of their viral single ‘Beggin’.

Måneskin broke through this year when the glam‑rock quartet surprised everybody by winning the Eurovision Song Contest with a rap/rock mashup called ‘Zitti E Buoni’. The song immediately went to number one on Spotify, and to the top of several hit parades in Europe. A second single released a few months later, ‘I Wanna Be Your Slave’, was also successful all over Europe, and was further propelled upwards by a later duet version with Iggy Pop.

So far, so normal — but then something strange happened, and it perfectly illustrates the random weirdness of the Internet, especially TikTok. A song that Måneskin recorded in a few hours in 2017, at the very start of their career, went viral on the social video sharing platform, thanks to a number of glow‑up and karaoke challenges.

‘Beggin’ promptly went to number one on the Spotify global chart, and started to climb the charts everywhere in Europe. Eventually it went to number one in nearly a dozen countries, reached number six in the UK and became the band’s first entry in the US charts.

By the middle of the summer, ‘Beggin’ had become the band’s biggest worldwide hit. From interviews it was clear that the band had mixed feelings about a cover song they recorded hastily at the start of their career superseding their self‑written and more expensively produced recent releases, and they refused to promote it. Yet at the time of writing, ‘Beggin’ was still flying high around the world.

The X Files

Let’s look at what happened in 2017. Speaking from Metropolis Studios in Milan, engineer and mixer Alessandro Marcantoni has the full story. He spent only two days recording four tracks by an up‑and‑coming teenage band. According to Marcantoni, it all started with the band performing at X Factor Italia that year, eventually coming in second.

Alessandro Marcantoni at the current incarnation of Metropolis Studio, Milan.

Alessandro Marcantoni at the current incarnation of Metropolis Studio, Milan.

“They performed two originals and several covers on X Factor, and Sony Music, which is a partner of the X Factor, each year selects some of the artists that appear to record an EP. Måneskin had already recorded their two original songs elsewhere, and then came to Metropolis to record four more covers, all of which appeared on their Chosen EP. Here at Metropolis we have recorded acts that appear on the X Factor for the first 13 seasons.”

The four covers that Måneskin had selected to record were songs by Black Eyed Peas (‘Let’s Get It Started’), the Killers (‘Somebody Told Me’), Ed Sheeran (‘You Need Me, I Don’t Need You’), and the Four Seasons (‘Beggin’). A fifth cover that appears on the Chosen EP, ‘Vengo Dalla Luna’, by Italian rapper Caparezza, was recorded and mixed by Marcantoni at Metropolis a month earlier.

‘Beggin’ was written by Bob Gaudio and Peggy Farina and became a minor hit in 1967 for the Four Seasons. It was remixed in 2007 by French DJ Pilooski, and his version reached number one on the UK Dance chart. That same year, Norwegian hip‑hop duo Madcon released a new version of the song, with added rap sections. It became a big hit all over the world, reaching number five in the UK and number one in a number of other European countries.

‘Beggin’ was written by Bob Gaudio and Peggy Farina and became a minor hit in 1967 for the Four Seasons. It was remixed in 2007 by French DJ Pilooski, and his version reached number one on the UK Dance chart. That same year, Norwegian hip‑hop duo Madcon released a new version of the song, with added rap sections. It became a big hit all over the world, reaching number five in the UK and number one in a number of other European countries.

Exactly what prompted Måneskin to cover ‘Beggin’ is not known, but theirs is a high‑energy, uptempo funk‑rock version starting with an a cappella by singer Damiano David. His huge, raspy voice is the most defining characteristic of the song, while the musical arrangement is basic: just drums, bass, and a single guitar. According to Marcantoni, it was the same with the other four songs.

“They had just performed these cover songs at the X Factor, and they wanted to record them just like their performances, so very simple. I tried to do some production by getting them to add some instrumental overdubs, but they were not into that. They performed all songs live in the studio, and later overdubbed the vocal. While they all played together, we focused on one instrument during each take. So during these band takes we first tried to get the drums, and then the bass, and then the guitar. Damiano sang the vocals by himself, later on.”

Metropolis

Before elaborating on what went on at Metropolis in 2017, we need to go back further in time to set the scene with regards to the studio, and Marcantoni. Metropolis (no relation to the London studio of the same name) first opened its doors in 1990, with three recording spaces, and quickly became one of Italy’s leading studios. The studio has moved twice since then, each time reducing the amount of rooms as the demand for recording studios declined.

Metropolis’ second location had two studios, with a Yamaha DM2000 desk and Genelec and Dynaudio monitors in Studio 1. It was here that Marcantoni worked with Måneskin. Metropolis has since moved to a third location, with only one studio. The operation is now fully in the box, with two Avid S1 controllers, a Dangerous Music Monitor ST+SR, monitoring from ATC SCM100ASL Pro and Amphion One18, plus an Amphion Amp700, and large collections of outboard, microphones and musical instruments.

Metropolis Studio in 2017, where Måneskin recorded ‘Beggin’.

Metropolis Studio in 2017, where Måneskin recorded ‘Beggin’.

Alessandro Marcantoni joined Metropolis in 2003 as an assistant engineer, and quickly went up the ranks to become senior engineer. He’d played several instruments as a child, and performed with various indie rock bands as a teenager. He then studied Drama, Arts & Music at the University of Bologna, and did a Sound Engineer course at the SAE Institute in Milan. Marcantoni still works for Metropolis, but is also active as a freelance engineer in other studios, and as a front‑of‑house engineer in large venues in Europe. He’s also occasionally involved as an educator with IULM University and the SAE Institute, both in Milan.

“I know most of Italy’s top engineers,” says Marcantoni, “and have learned from them. But I am mostly influenced by American and British engineers and mixers. I work with all kinds of music, and I like a lot of different music, but my roots are in growing up with rock, in all its variations. But, of course, I do my best to remain up to date with the latest sounds in pop and hip‑hop.

“In general I’ll work with the song and the tracks that I have, and make everything sound as good as possible, without thinking too much about genre or time periods. With Måneskin there clearly were ’60s and ’70s influences, and at the same time I wanted to make their recordings sound current. They are often linked to the sound of Franz Ferdinand, for example.”

Alessandro Marcantoni: They had just performed these cover songs at the X Factor, and they wanted to record them just like their performances... I tried getting them to add some instrumental overdubs, but they were not into that.

Quick On The DAW

Back in 2017, when Marcantoni spent one day in the then Metropolis Studio 1 with a promising teenage band, it was a routine session for him. He and the band had a brief to record four cover songs, which he mixed the following day. When asked how long the entire project took, he burst out laughing: “With the X Factor I have very few days for each project! But each working day was definitely more than eight hours, so we probably spent two or three hours recording each song, and I would have spent up to two to three hours on each mix. The first song took longer to record, and to mix, as I was setting up the sounds. After that, because the instrumentation and recording chains did not change, things went a lot quicker. But if I had felt that I had needed another day to get the result we wanted, I would have reorganised my schedule to free an extra day.

“I don’t tend to work with templates. I create each session from scratch, whether it’s a mix session or a recording session. However, if I record the drum set in our studio, I’ll start with the settings I have for that from a previous session, just to speed things up. I may have done a session with another drummer the day before, so when Maneskin came in, Ethan [Torchio] spent some time tuning our drums, and we worked on getting the sound he wanted. But whatever template I have is purely there to speed up my input list, and to have my cue list for headphones ready. It’s not for the sound.”

Working from memory, old gear lists and photos, and the track names in his mix session for ‘Beggin’, Marcantoni retraces his steps, both for the recordings and the mixing. “For the kick I would have used a Shure Beta 52A on the inside, a Neumann U47 [FET] on the outside, and a Royer Labs R‑122 placed close to the kick drum pointing to the snare, for a mono drum kit track. On the snare I used a Shure SM57 at the top, and a Shure Beta 57 at the bottom. I duplicated the top snare track to create another effect setting for the rimshots.

“In addition I had one Neumann KM‑184 for hi‑hat and another KM‑184 for the ride cymbal, a couple of AKG C414 XLII mics as overheads, and two Neumann U87s for ambience. The toms had Beyerdynamic Opus 87 mics. I would have avoided the Yamaha desk for the recording chains, so the mics would have gone through external mic pres. I most likely would have used API 512C’s for the kick and the snare, and Focusrite ISA 828/430 for the other drum tracks. They would have gone into the Apogee Symphony MkI, and the Avid HD I/O.

“I recorded the bass DI, using the Manley Voxbox channel strip, which I still often use for DI. That sounds great because it adds a tube sound at the recording stage. I will have used an Empirical Labs Distressor while recording the bass. For the guitar, I used a Shure SM57 and a Royer R‑122 on one cabinet, which I think was our Fender Reverb Pro. The two guitar mics will have gone through the API 512C, and I do not use compression while recording electric guitars. The vocal mic was a Brauner VM1, recorded through an API 512C. I think I used another Distressor to keep the spikes under control.”

Post‑production

Marcantoni comped the tracks as he was recording them. “I knew I would not see the guys again the next few days, as they were busy with the talent show, so I made sure we did the comps while they were in the room, so they could have their input. The final drum track was comped together from three different takes. The drummer had played with a click in his headphones, but I did some minimal time adjustments where they had started to drift.

“We spent a bit of extra time doing additional vocal takes to fine‑tune Damiano’s English pronunciation. For the songs in Italian we did maybe only three takes, but in this case there were nine takes. The extra takes were not complete takes, but purely some sections. I didn’t use any Auto‑Tune or Melodyne, but did some minor pitch adjustments using Pro Tools’ Elastic Audio — maybe some words or parts of words — and I may have done some minor timing adjustment. But Damian is exceptionally talented and it’s very easy for him to sing in tune, so there wasn’t much to correct.”

Marcantoni also began rough mixing during the recording: “I try to get the sounds right from the moment I record them. I then work on instruments or sections of instruments during the recordings, trying to get them to sound pretty good. At that point it’s easy to incorporate feedback from the artist or band. I’ll do some more mixing by the end of the day, and I normally end up with something that sounds pretty refined. I may get the sounds to 80 percent of the final mix.”

The Mix

Marcantoni went into his room at Metropolis the next day to get his mixes to 100 percent. Clearly there was some polishing going on, but as he had to complete four mixes in one day, Marcantoni’s polishing was minimal compared to what’s done in an average mix today, which tends to take a day per song, and sometimes far longer.

The ‘Beggin’ Pro Tools session contains just 21 audio tracks.

The ‘Beggin’ Pro Tools session contains just 21 audio tracks.

Download this ZIP file of a high-res screenshot and enlarge to see full details.

![]() inside-track-1021-protoolssession-screenshot.jpg.zip

inside-track-1021-protoolssession-screenshot.jpg.zip

The mix session for ‘Beggin’ is indeed exceptionally simple, with the audio consisting of 13 drum tracks, one bass track, four guitar tracks, and three vocal tracks. Even this grand total of 21 tracks was reached only by splitting five of the original 16 audio tracks; Marcantoni wanted to separate some parts onto different tracks to be able to treat sections differently. He did this with the rimshot snare, guitar and vocals.

Marcantoni added a number of aux effects tracks, namely three for the drums, three for the bass and guitars, and five for the vocals. All instruments go to an Instrument Group aux and the vocals to a Vocal Group aux. Finally there’s a master track, and the click, leading to a full total of 36 tracks.

“For me balancing levels is the main thing in a mix,” Marcantoni elaborates. “But I of course also work on the sounds, and any sonic problems that may come up when I’m mixing. There are many greyed‑out plug‑ins in the inserts, for example the Avid Pro Compressor, Pro Expander, Channel Strip, and EQ3 7‑band. I used these for rough mixes during the recordings with no latency, and I then disactivated them and added new plug‑ins during the mix. With the drums, many instances of the Pro Compressor and Channel Strip remained on the audio tracks, and I often used the EQ3 7‑band for basic EQ.

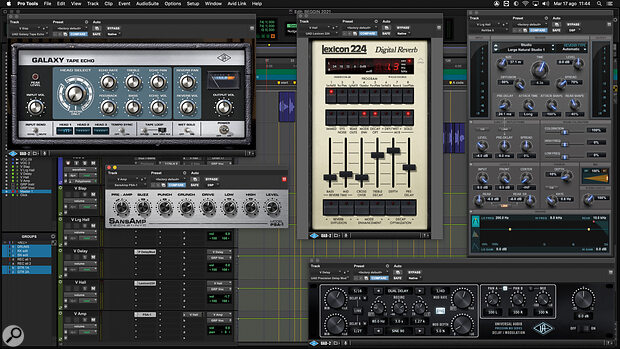

“The main sonic treatment on the drums came from the aux effects tracks: the Drums Ambient, which had a UAD EMT140 for some plate reverb with a small decay and some predelay, and the Drums Amp, with the SansAmp for parallel distortion. All drums go through the MF Drums group track, which has the UAD SSL G‑channel and Avid EQ3 7‑band, for some compression and minor EQ adjustments.

“I kept the bass in place with the UAD 1176LN E, and it also has a send to the Room aux, which has a UAD Ocean Way room reverb. I added compression to the guitar tracks with the UAD LA‑2A S, and there are sends to the Hall aux, with a UAD Lexicon 224, on the two main guitar tracks. The two guitar tracks that I pulled out for the B sections have sends to the Hall and to the Chorus aux, which has a UAD Studio D Stereo Chorus.”

Vocals

“All vocal tracks have the same inserts: Avid EQ3 7‑band, UAD 1176 LN, Mäag EQ4, and again the 7‑band. The main difference is in the plug‑in settings and in the sends. The a cappella at the beginning of the song is sent to the Very Large Hall aux with the Avid ReVibe II, as well as the Hall aux with the UAD Precision Delay Mod, and the V Hall which has another instance of the Lexicon 224. I wanted the a cappella to sound larger than the other vocals, which have only the 224 and a send to the V Slap aux, with a delay from the UAD Galaxy Tape Echo.

. Vocal effects included the UAD Galaxy Tape Echo, Lexicon 224 reverb, and a send to a bus containing Avid’s SansAmp plug‑in.

Vocal effects included the UAD Galaxy Tape Echo, Lexicon 224 reverb, and a send to a bus containing Avid’s SansAmp plug‑in.

“The main vocal tracks also have a send to the V Amp track, on which I had the SansAmp, for some more edge. The singer has a very raspy voice, which I think sounds great, and the SansAmp enhances this. All vocal tracks go to the Group track, on which I have two EQs and the UAD Precision De‑Esser. I use volume automation a lot on individual tracks, so if I use de‑essers on them, it can emphasise the esses. For that reason I prefer to have the de‑esser on the subgroup at the end of the chain. It makes it easier to control things.”

Instrument Group & Master

“The instrument group track has the Brainworx bx_digital V3 M‑S EQ, and the only thing I did with that is make the instruments wider. I wanted to open up the stereo image, because the song is almost in mono. Only the drums are in stereo, and although I used two mics on the guitar and hard panned them, they still picked up the same part. It’s not a double guitar, so sounds pretty mono.

“Both the Instrument and Vocal Group tracks are sent to the Master track, on which I again have the bx_digital, again to widen the image. I guess I felt I had to do it twice, because once was not enough! I used the Precision Maximizer and Precision Limiter for volume when I sent the mixes out for approval, but I took them off when I sent the mix to the mastering engineers, Pietro Caramelli and Claudio Giussani at Energy Mastering.”

Caramelli and Giussani added their own bit of final polishing. Naturally, none of those involved expected one of the songs to become a worldwide hit four years later, but clearly, the quick work that was done by Marcantoni in 2017 was of high enough quality to hold its own in the charts of 2021.