Olivia Rodrigo stormed the charts earlier this year with her breakthrough single ‘Drivers License’. LA’s rising star Mitch McCarthy talks us through the mix.

In early February of this year, after nearly a decade of hard work, Mitch McCarthy hit the big time. One of many songs he had mixed, ‘Drivers License’ by Olivia Rodrigo, became the biggest hit of 2021 so far, and broke many records in the process, including for biggest‑ever first‑week song on both Spotify and Amazon Music. The song went to number one in at least 25 countries, including the US and the UK, and was, at the time of writing, mid‑February, still dominating the charts everywhere.

In recent years, McCarthy has enjoyed a number of high‑profile credits, including Bebe Rexha, Melanie Martinez, Carly Rae Jepsen, Meghan Trainor and Giorgio Moroder, but the mega‑success of ‘Drivers License’ is in a different league altogether. This magazine’s Inside Track series tries to cover number one recordings whenever possible, and so when McCarthy received the inevitable email with an interview request, it added to him feeling pretty much on top of the world.

“Yeah, the success of ‘Drivers License’ is crazy,” raved McCarthy, via Skype. “I don’t think any of us expected it to do what it’s doing, just the magnitude of it. We’re all really excited and stoked about it! It still hasn’t really hit me yet, because the last year has been so crazy for everyone, with Covid‑19. I guess I’m still in a bit of a shock. In a good way! And then there’s doing this interview. I’ve been reading SOS for 15 years and being in it has been one of my goals for a long time!”

Salad Days

The ‘we’ that McCarthy refers to means everyone who worked on the single, but in particular the song’s co‑writer and producer, Daniel Nigro, as well as Ian McEvily, who manages both Nigro and McCarthy for State of the Art Downtown LA, aka SOTA DTLA (formerly Rebel One). Three years ago McCarthy set up his mix room, where he mixed ‘Drivers License’, in the same building where the management company is based.

McCarthy started working with SOTA DTLA in 2014, after cutting his teeth with songwriter and producer duo Mario Marchetti and Marc Himmel, and before that working in an Orange County studio called S1 Studios (now defunct). “I’m originally from San Mateo, a suburb of San Francisco,” elaborates McCarthy on his background. “I started playing guitar in grade school, which lead to me joining the middle school jazz band. I also played saxophone in the regular school band. I was a fan of all music, from Nirvana to Bill Evans to Eminem.

“During high school I wanted to know how to record myself, and discovered Pro Tools. I soon got into making beats and laying guitar riffs over them, and this transitioned into me falling in love with the engineering side. After high school, in 2008, I went to Expression College for Digital Arts in Emeryville, now called SAE Expression College, which was fantastic. I worked with large‑format consoles, a ton of other analogue gear I never had access to, and gained a lot of technical knowledge. I received my Bachelor’s Degree in Sound Arts.”

In 2011, McCarthy moved to LA, and further cut his teeth at the two above‑mentioned studios, crediting Marchetti in particular for teaching him a lot about vocal production. “When recording bands at S1 Studios, more and more people started to ask me to mix their records. This was also the case when working for Mario and Marc. I really fell in love with the process and technicalities, and after I left Mario’s studio, I decided to strictly focus on mixing. It’s rare that I do a full recording session these days.”

Racking Up

Mitch McCarthy at his studio in LA.

Mitch McCarthy at his studio in LA.

In part because of his experiences in working with analogue at Expression College for Digital Arts, McCarthy incorporates several choice pieces of analogue gear in his studio, some of which were in use for his mix of ‘Drivers License’. Although still only 31, McCarthy reckons that he is “of the last generation that actually cares about analogue. I have always been a gear head, and going to college solidified that. I got completely obsessed! Of course, I grew up in the digital age, and for me working with music has always been about Pro Tools. But once you hear analogue and work with it, you realise it does something special.

“I can hear the difference, and even if it’s just that extra five percent, things need to sound as good as possible. For instance, when I compare the Dangerous BAX EQ plug‑in with the hardware version, I find that the hardware sounds warmer and more open than the plug‑in. Also, when you work with analogue gear, it forces you to listen with your ears. If you’re sitting in front of a DAW just fixated on a certain plug‑in you tend to be listening with your eyes. But when you’re twisting a physical knob, you’re purely focused on your ears and the music.”

Despite his love of analogue, McCarthy has, like many of his colleagues, come to the conclusion that it’s no longer practical to work purely on analogue. “I don’t want to spend hours recalling on a desk, so I am only incorporating analogue pieces that fit in my workflow. I have a hybrid setup in my studio. My ‘All Groups’ in Pro Tools go via my Apogee Symphony into the Dangerous Music 2‑Bus+ summing box, and I have my Dangerous Music Liaison patched into the ‘EXT Insert’ on the 2‑Bus+. The Liaison is a digital patch bay, which allows me to quickly audition my outboard gear with the push of a button. The signal then goes back into Pro Tools via my Dangerous Convert AD+ via AES. I love Dangerous stuff, because it is built very well, simple to use, and super transparent and clean. It works great for pop music.

McCarthy is a big fan of analogue processing. Pictured is one of his outboard racks, housing (from top) a Manley Nu Mu compressor, a Hendy Amps Michelangelo valve EQ, a Dangerous Music BAX EQ, and a Warm Audio Bus Compressor.“My outboard consists of the Dangerous Compressor, Dangerous BAX EQ, SSL Fusion, Warm Audio Bus Compressor, Manley Nu Mu, and the Hendy Amps Michelangelo. The latter is one of my favourite pieces of gear. It’s a tube‑based EQ. I wanted something that’s really colourful, because all the Dangerous stuff is so transparent. I ended up swapping the stock tubes it came with for ‘Black Sables,’ on the advice of a mastering engineer friend, Matt Gray. That change took it over the top. I can push a source to sound very dirty and saturated. The parameters are simple on the Michelangelo: low, mid, high, and air buttons, and an Aggressive knob that allows you to drive the unit. Most of the time I run the Michelangelo in parallel, something the Liaison allows me to do, and I drive it with extreme settings, which I then blend in with the master signal.

McCarthy is a big fan of analogue processing. Pictured is one of his outboard racks, housing (from top) a Manley Nu Mu compressor, a Hendy Amps Michelangelo valve EQ, a Dangerous Music BAX EQ, and a Warm Audio Bus Compressor.“My outboard consists of the Dangerous Compressor, Dangerous BAX EQ, SSL Fusion, Warm Audio Bus Compressor, Manley Nu Mu, and the Hendy Amps Michelangelo. The latter is one of my favourite pieces of gear. It’s a tube‑based EQ. I wanted something that’s really colourful, because all the Dangerous stuff is so transparent. I ended up swapping the stock tubes it came with for ‘Black Sables,’ on the advice of a mastering engineer friend, Matt Gray. That change took it over the top. I can push a source to sound very dirty and saturated. The parameters are simple on the Michelangelo: low, mid, high, and air buttons, and an Aggressive knob that allows you to drive the unit. Most of the time I run the Michelangelo in parallel, something the Liaison allows me to do, and I drive it with extreme settings, which I then blend in with the master signal.

“I have Amphion Two18 and One18 monitors in my studio. They are passive, so I use them with the Amphion 500 amplifiers, which I have two of. Since I got these monitors I have not looked back. They just kill it for me. I love them. I also have a set of little Avantones that are super lo‑fi and sound like a radio. I’ve been thinking of getting some big main speakers, but clients don’t come round very often anymore. We’re just a block from the new Warner Brother’s building, and while I work with WB quite a lot, an A&R has visited my studio maybe once in the three years I’ve been here. These day’s I think the A&R folks and producers are used to sending notes via email rather than coming in for revisions. It’s also rare that I talk to the artist directly, my main communication is with the producer and label.”

Mitch McCarthy: I have Amphion Two18 and One18 monitors in my studio... Since I got these monitors I have not looked back. They just kill it for me. I love them.

Great Import

Having set the scene of where and with what he works, McCarthy moved on to the how of his working methods, by describing his process after he receives the files for a mix. “There are only three producers who I work with consistently who use Pro Tools, one being Dan Nigro, another is Leroy Clampitt, aka Big Taste [Madison Beer, Justin Bieber], and also Michael Keenan [G‑Eazy, Melanie Martinez]. The others work on Ableton or Logic, in which case I get sent stems. I ask to be sent stems with processing on individual tracks but without master bus processing, and wet and dry vocal stems, with separate effect tracks. Many producers spent a lot of time on their vocal effects, and you can’t recreate them unless you have someone in the room with you. If they aren’t completely set on the way something sounds, I ask them to include a ‘dry’ folder with dry stems.

“I import the stems into a Pro Tools session, or start organising the Pro Tools session I’ve been sent, so that the session looks the way I like it, with my specific routing and track layout. This is always called my ‘edit’ session. I will fix pops and clicks, consolidate similar tracks, tune vocals, and colour‑coordinate tracks. It’s just general organisation. Lastly, I always request a reference mix. I normally have the reference at the top of my session in Pro Tools. It’s crucial to hear what the artist, label, producer and so on have been listening to.”

McCarthy’s process is informed by his time at music college and his experiences with analogue gear. “You really need to understand how analogue gear works to be able to work with it effectively. With plug‑ins you can often get by with trial and error, though it still helps to understand analogue. For example, to be able to use all the UAD emulations effectively, you need to know how the analogue versions work.”

Making Gains

Another crucial aspect of working in analogue that transfers to digital is gain staging. “It’s important for me when organising my mix session that I start with all faders at zero. Imported stems are at zero anyway, but if I’ve been sent a Pro Tools session, I’ll do a Save As, and then I’ll print all tracks, with effects, that don’t have the faders at zero. So in a way I create stems inside the session, and to be able to identify them I add a P to the track name, for ‘print.’ I’ll then deactivate the original tracks. This makes it easier to take the session I’m given as a starting point, without always having to refer back to what the fader positions were in the original session. I can always re‑activate tracks if I need to change something.

“Most of the Pro Tools sessions I get sent are slammed and individual tracks are clipping,” adds McCarthy. “Once I have organised my session and have all tracks at zero, I import my template, which is essential for gain staging. Part of my template is a series of group aux tracks, like All Lead vocals, All BVG, All Drums, All Bass, All Synth and so on. These go straight to the outputs of my Apogee Symphony, and from there to the inputs of my Dangerous 2‑Bus+. I’ll bring individual tracks down prior to these group aux tracks to make sure everything hits my analogue chain at the right level.

“Another aspect of my template is parallel effect tracks. I’m a big fan of parallel compression, parallel EQ, parallel everything. You can really do some magical stuff with it. For example, I have three different parallel drum bus compressors, one light, one heavy, and one saturated, and I can blend them in, instead of processing directly on the track. The samples that producers are using today are often already so compressed and processed, you don’t want to process them directly. It starts to make things sound small. This is where parallel processing is handy, because it makes things sound bigger and fatter and louder, all without destroying the original signal.”

In The Mix

Once McCarthy has his mix session laid out and organised the way he wants it, he starts actually mixing. “I take anywhere from a couple of hours to a couple of days per mix,” explains McCarthy. “It really depends. Part of my process is that I am a believer in the first couple of hours being the most important. So I push to make super‑quick moves, because your first instincts are usually right.

“I’ve had instances where I’ve done a quick mix, and continued working on that mix, and when I then pulled that first mix up days later, I thought: ‘That was it!’ When you keep working on a mix you get used to the way things sound, and then your brain adjusts, and you risk destructively tweaking things. Your first instincts are key to creating a good mix. Obviously, mixers are often called in as that extra pair of ears that are still fresh.

“I always start the mix working on the drums and percussion, and then I bring in the bass, and then the other instruments, and finally the vocals. I’ll carve out a space for the vocal, and make sure it sits right on top. In general, also, I’m a believer in less is more. This means that I don’t often use tons of plug‑ins, though it varies very much on the song, of course. I have a bunch of parallel compression tracks in my template, and may use some of the plug‑ins already there, but if something already sounds good, I don’t touch it. Part of your job is to know when not to touch things. If at all possible, simple is always better for me.

Mitch McCarthy: I am a believer in the first couple of hours being the most important. So I push to make super‑quick moves, because your first instincts are usually right.

Less Is More

‘Drivers License’ is a great example of the principle that less is more and simple is better, in terms of the songwriting, the arrangement, the production and the mix. The song has been hailed as a return to more traditional songwriting, at a time when the pop charts in the US in particular have been dominated by trap music and TikTok‑influenced brevity, with songs increasingly coming in under three minutes and pared down to verse‑chorus‑verse‑chorus. With a track length of 4:02, ‘Drivers License’ defies the trend for short songs, and it even has a middle eight!

McCarthy explains the ins and outs of his mix. “I normally haven’t heard what Dan’s been working on when he sends sessions to me, so they’re new to me. He’ll send me a reference, and I’ll listen to that once and make notes. We also often have a phone call in which he explains what he may be concerned about and what he wants me to address. He’s very specific about things, so if I want to change something, I’ll give him a call to discuss it.”

Cleaning Up

“This happened with ‘Drivers License,’”, explains Mitch, “because there was a lot of mouth noise in the lead vocal in the first verse and the first chorus. It’s a very intimate‑sounding part of the song, just piano and vocal, so I asked him whether it was part of the vibe, but he said, ‘No, no, fix it!’ So I put these vocals through the iZotope RX 8, to clean up some of these pops and clicks and weird noises, and also the esses that were still hard, even after the de‑esser. The other issue was that the vocals were distorted a little in one part. Olivia was happy with Dan’s comp and the emotion was there, so the decision was made to stick with the take, and I again used RX to fix the distortion.

“The song already sounded really good when I received it, and again, part of my job is not to mess things up. Dan wants things to sound emotional and then for that extra 10 or 20 percent to be added to the sonics. But he does not want me to reinvent the wheel. This is also why this session is so minimal insofar as plug‑ins are concerned. Most of the work with plug‑ins is on the vocal chain.”

My first instinct when listening to the song was that it needed to breathe and sound dynamic, and also, not to make it sound like an in‑your‑face, bright pop record. So it was about dynamics and making it sound warm. There’s not that much going on in the track, so what’s there needed to have its place. Dan was in a band in the ’00s, he comes from the analogue world and is all about things sounding dynamic and warm. We really see eye to eye on that.

“The entire structure of the track is a build‑up to the middle eight, which is the biggest part of the song. It’s like, ‘OK, everything leads up to this moment where the middle eight comes in, and then it’s like, boom, it hits you.’ I like to work from top to bottom, which means starting with the most important part, and in this case that was the middle eight, and because I start with the percussive elements, I started the mix with drums and percussion in the middle eight.”

Drums

DMG Audio’s EQuilibrium equaliser makes numerous appearances in McCarthy’s mix of ‘Drivers License’. Here, it’s filtering some low end and cutting the mids on Olivia Rodrigo’s lead vocal.Mitch’s mix template is set up with drum processing ready to go, but for this mix much of it didn’t get used. “I did not use many of the parallel compression tracks that are in my template, because in this track it was not necessary for the drums to slam. The Drums P1 and P2 tracks, one with the Neve 33609 and the other with the Chandler Limiter, are also from my template but inactivated. I also did not use my Drums group track, with the Soundtoys Decapitator and Black Box Analogue Design HG‑2, for the same reason. It was too much and sounded too big!

DMG Audio’s EQuilibrium equaliser makes numerous appearances in McCarthy’s mix of ‘Drivers License’. Here, it’s filtering some low end and cutting the mids on Olivia Rodrigo’s lead vocal.Mitch’s mix template is set up with drum processing ready to go, but for this mix much of it didn’t get used. “I did not use many of the parallel compression tracks that are in my template, because in this track it was not necessary for the drums to slam. The Drums P1 and P2 tracks, one with the Neve 33609 and the other with the Chandler Limiter, are also from my template but inactivated. I also did not use my Drums group track, with the Soundtoys Decapitator and Black Box Analogue Design HG‑2, for the same reason. It was too much and sounded too big!

“Because Dan’s source material sounded great it didn’t need much, but several of the audio tracks have the DMG Audio EQuilibrium EQ, which is my go‑to EQ. I love it. It’s either that or the FabFilter Pro‑Q 3. All the EQ here is subtractive, I’m not a big fan of boosting. One of the claps also has the Decapitator to darken them and give them more body, and some dirt, and the sticks also have the Soundtoys EchoBoy, to give them more movement. But it’s super subtle.

“The panning of the claps came from Dan, and I left it because it’s really important. It creates movement and excitement in the track. For the rest mixing the drums and percussion was about levels, and again making sure things build up to that middle eight. All these tracks go to the All Drums Aux. I have the Slate Digital Virtual Mix Rack on each of the group tracks, in general adding some warmth. I ride the volume on these busses, and as I mentioned, I use them to adjust the level before they hit the 2‑Bus+ summing mixer. But in general I prefer to automate the volume on the individual tracks.”

Instruments

“Again, there are very few treatments here, the most important being the Waves RCompressor on the Juno sub, which I side‑chained to the kick. There was some weird information going on in the low end in the middle eight, so I put on a pretty heavy side‑chain. For the rest it’s just the EQuilibrium EQ on the Juno bass and again the EQuilibrium on the strings, and then the piano has the Dangerous Music BAX EQ and the Lo‑Fi. The piano was a real piano recorded in Dan’s studio, and it sounded a bit dark, so I EQ’d it to add some presence, and also take out some low end that was not necessary. The Lo‑Fi is taking off some airy high end to make the piano sound warmer and more vintage, and the distortion is adding more body.

“That’s it for plug‑ins on the individual tracks. The four bass tracks go to the All Bass bus, and some of the synth tracks go to a Keys aux bus, and from there to the All Synth bus, and the other synth tracks go straight to the All Synth bus. The Keys track has a Keys P parallel, with a UAD LA‑2A and a Mäag EQ4, which I am blending in with the main Keys track. I automated that, so different amounts of the parallel are added at different times in the song.”

Vocals

There are seven aux effects tracks for the vocals: first a track called Doubler with the Soundtoys MicroShift, and then a track called Parallel Vox with the UAD EL‑8 Distressor. Next are tracks called Hall, Plate and Chorus Verb, each with the Valhalla Vintage Verb, and two delay tracks, called 1/4 and 1/8, each with the Soundtoys EchoBoy. The first of the actual vocal audio tracks is Olivia Rodrigo’s lead vocal, and this is the only track in the session with many plug‑ins. The track has six inserts: EQuilibrium, Waves CL76, McDSP MC404, FabFilter Pro‑DS, Oeksound Soothe 2, and Valhalla Vintage Verb. Six effect sends go to all but one of the above‑mentioned aux tracks. There’s also a Bridge Lead vocal with only the EQuilibrium, and seven backing vocal tracks, some of which have the MC404 plug‑in inserted. All the backing vocals are sent to the BG Vox aux at the top.

FabFilter’s Pro DS and Oeksound’s Soothe 2 plug‑ins work in tandem to eliminate sibilance and harshness in the vocal recordings.

FabFilter’s Pro DS and Oeksound’s Soothe 2 plug‑ins work in tandem to eliminate sibilance and harshness in the vocal recordings.!["The [FabFilter] Pro‑DS is my de‑esser of choice. I love that plug‑in." "The [FabFilter] Pro‑DS is my de‑esser of choice. I love that plug‑in."](https://dt7v1i9vyp3mf.cloudfront.net/styles/news_preview/s3/imagelibrary/I/IT_0421_06a-XS2h5U8RM0rsA_HQ_1oNAjUFSP4ODiVN.jpg) "The [FabFilter] Pro‑DS is my de‑esser of choice. I love that plug‑in."McCarthy explains: “This chain is typical for what I do on vocals. The EQuilibrium takes out below 100Hz, and dips at 350Hz and 1000Hz. Then I have some compression from the CL‑76, with a ratio of 4:1, and a medium attack and a very slow release. Sometimes I use the Waves RVox or UAD 1176 instead of the CL‑76. It really depends on the singer. I am using some kind of multiband compression on the vocal, and I have been using the MC404 for this for years. It is one of my favourite plug‑ins. For dynamic singers it provides so much control, and it really tames high‑mid harshness. I use a preset that I made and that I always start with, and then I end up tweaking it depending on the singer.

"The [FabFilter] Pro‑DS is my de‑esser of choice. I love that plug‑in."McCarthy explains: “This chain is typical for what I do on vocals. The EQuilibrium takes out below 100Hz, and dips at 350Hz and 1000Hz. Then I have some compression from the CL‑76, with a ratio of 4:1, and a medium attack and a very slow release. Sometimes I use the Waves RVox or UAD 1176 instead of the CL‑76. It really depends on the singer. I am using some kind of multiband compression on the vocal, and I have been using the MC404 for this for years. It is one of my favourite plug‑ins. For dynamic singers it provides so much control, and it really tames high‑mid harshness. I use a preset that I made and that I always start with, and then I end up tweaking it depending on the singer.

“The Pro‑DS is my de‑esser of choice. I love that plug‑in. The Soothe 2 that follows it eliminates some annoying harsh resonance in the vocal. I again use a preset I made as a starting point. This track is sent to the Parallel Vox track, on which I have the Distressor, with Crush set to hard. I automated the Parallel Vox aux track to give some more body and presence when needed. I also automated the Doubler track with the MicroShift, adding more of the chorus to make the voice bigger, and in the verses where the voice needs to sound more personal, I backed it off and have the vocal more dry and in your face. Dan did most of the delays and reverbs on the vocal, so I only tweaked the settings lightly. All lead vocal and vocal aux tracks are routed to the All Lead aux group track at the top, which again has the Virtual Mix Rack.”

Summing & Mastering

Mitch elaborates on his summing process for ‘Drivers License’: “From the aux groups the signal goes via the Apogee Symphony to the 2‑Bus+ for summing to stereo, and I only have the Dangerous BAX EQ in the analogue chain, filtering at 36Hz and at 28kHz. I love using the high‑pass and low‑pass filters on the BAX, which makes the mix sound super tight. After that the signal returns into Pro Tools, via my Dangerous AD+, and I then have five plug‑ins on the Master track: the Shadow Hills Mastering Compressor, going into the Plugin Alliance Mäag Audio EQ4, the UAD Precision K‑Stereo, the UAD Sonnox Oxford Inflator, and the iZotope Ozone 9 Maximizer. I print the mix on the track below this.

“I apply the Shadow Hills very minimally, because I wanted the song not to sound too compressed. I am using the Opto setting, with probably just 0.5 to 1 dB of gain reduction. The side‑chain option is on so it is letting that low‑end information through, but again, it’s super subtle. The Mäag EQ4 does just some subtractive EQ, pulling out a little bit of sub and dipping at 1dB at 160Hz, because the middle felt a tad too boomy. This tightens up the low end after the compressor.

On the master bus, the UAD K‑Stereo plug‑in provides some subtle stereo widening.

On the master bus, the UAD K‑Stereo plug‑in provides some subtle stereo widening.

“The K‑Stereo is one of my favourite plug‑ins, and I am adding 1dB of gain to the Sides, which adds some space and width. Sometimes I boost 2.5 or 3 dB to the Sides. I really like to automate Sides; I am a big fan of M‑S processing, and as an example, in the verses I may have the Sides at zero, during the pre‑chorus I’ll then boost the Sides 1dB, and then during the chorus I will boost the Sides 2dB. When the second verse hits I will bring the Sides down to, say, 0.5dB, and so on. I really like to play around with that, because it creates more width and emotion throughout the song.

"After the K‑Stereo is the Inflator, which adds a little bit of volume, as does the iZotope Ozone 9 Maximizer, to get everything up to volume and make sure I match the reference mix.”

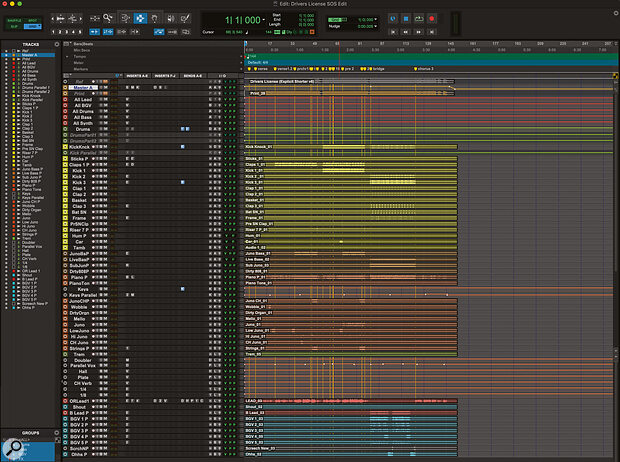

Session View

McCarthy's Pro Tools session for ‘Drivers License’ contains only 64 tracks; minimalist by today's standards.

McCarthy's Pro Tools session for ‘Drivers License’ contains only 64 tracks; minimalist by today's standards.

Download the ZIP file containing the larger view Pro Tools session screenshot.

![]() drivers-license-protools-session.jpg.zip

drivers-license-protools-session.jpg.zip

‘Drivers License’ has been commended for the simplicity of its production. With a tempo of 72 bpm it’s very much a ballad, and it’s been called ‘bedroom pop’ because of the relatively minimalist arrangements, centred around a piano and hand claps panned far left and right. Song transitions are marked by synths swells, and there’s a four‑to‑the‑floor kick in the second verse, but production only starts to sound full in the bridge. The song ends very intimately again, with only piano and vocal.

Consisting of 64 tracks, McCarthy’s mix session is, by modern standards at least, also relatively minimalist and simple. However, the arrangement is more elaborate than is immediately apparent, with 17 drum and percussion tracks (yellow), including four kick, four clap tracks, and four bass tracks (brown, including an 808). There also are 11 keyboard tracks (beige), including strings, three Juno tracks, a Mellotron track, organ and piano.

The 10‑track vocal arrangement (blue) at the bottom of the session has been comped down from a much larger recording session. Near the top of the session, in red, are McCarthy’s group aux tracks, consisting of All Lead, All BGV, All Drums, All Synth, and another Drums aux. There clearly are relatively few plug‑ins in this sessions, certainly nothing like the 40‑plus plug‑ins per track that appear in some sessions in our Inside Track series.