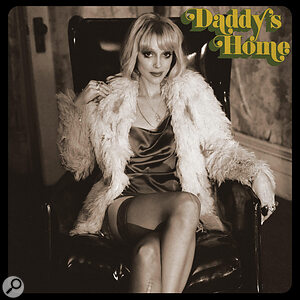

St Vincent (aka Annie Clark).Photo: Zackery Michael

St Vincent (aka Annie Clark).Photo: Zackery Michael

The experimental production behind St Vincent’s album Daddy’s Home made for an unusual and challenging mix.

“A good mix should be like opening a curtain, so it’s revealing the production, and it’s possible to hear things that you weren’t hearing before. Sometimes this means that the artist or producer wants to go back and adjust the production. When you clear up the vocal sound and get everything around it in focus, the artist may say, ‘Oh, I’m not sure I like this performance so much now that I can hear it more clearly and in context. I’m gonna re‑sing it.’”

Speaking is Cian Riordan, who has worked on productions by artists including Sleater‑Kinney, Foxygen, Mini Mansions, Doyle Bramhall II ft. Eric Clapton, Beth Ditto and Beck. Most recently, and most famously, he mixed St Vincent’s sixth studio album, Daddy’s Home, which was co‑produced by the artist and Jack Antonoff, famous for his production work for Taylor Swift, Lorde, Lana Del Rey and many more.

Both Antonoff and St Vincent, real name Annie Clark, are known for their fondness of wild experimentation, and they first worked together on St Vincent’s fifth studio album, Masseducation (2017). The futuristic electro‑pop and glam‑rock explorations of this album earned them a Grammy Award for Best Rock Song for the title song, and a nomination for Best Alternative Music Album.

The production of Daddy’s Home is more psychedelic and alt‑rock, with strong influences from the ’70s, so much so that it’s even, in the ultimate nostalgic move, released on 8‑track. Riordan’s mixes offered new perspectives on the production — his above quote refers to Clark wanting to re‑sing a vocal performance after hearing a first mix. On the entire album, Riordan’s mixes revealed things that led to extensive to‑ing and fro‑ing between Clark, Antonoff, and himself, often resulting in dozens of mix revisions, and sometimes more.

Riordan: “I don’t think there ever was a situation where the production was fully finished when they sent the session to me to mix. There were a couple of songs where the arrangements changed so much as a result of the revisions that I had to remix the entire song, as I wasn’t able to salvage my initial mix. ‘The Melting Of The Sun’ was one of them. It can be frustrating, as a mixer, to have to start over on a mix after 10 rounds of revisions. But I love Annie’s work, and this is an important record, so I wanted to make sure we got the best result possible.”

Beginnings

Riordan is a rising star in the international mix firmament, and with Daddy’s Home being one of his biggest credits to date, his eagerness to go the extra mile is understandable. Talking from his gorgeous new mix room, which he calls Pepper Tree Studio, located in a converted shed in the garden of his house in Pasadena, Riordan briefly elaborates on how he got to where he is, how this informs his current mix methods, and how he got the St Vincent gig in the first place.

Cian RiordanPhoto: Greg Carlin“I was born in Cork, Ireland, and my dad worked for Apple for most of my childhood, so we hopped around Europe, living in France and Holland, before we moved to the Bay Area in California when I was eight. I got a guitar when I was 12, and started playing drums a year later, but never took music very serious. At college I studied chemistry, and started playing in bands. I also always was the technical guy who was interested in recording.

Cian RiordanPhoto: Greg Carlin“I was born in Cork, Ireland, and my dad worked for Apple for most of my childhood, so we hopped around Europe, living in France and Holland, before we moved to the Bay Area in California when I was eight. I got a guitar when I was 12, and started playing drums a year later, but never took music very serious. At college I studied chemistry, and started playing in bands. I also always was the technical guy who was interested in recording.

“After I graduated it became clear that I far preferred music and recording to chemistry, and decided to have a career in music. Looking back I’ve had two mentors. The first is Andy Zenzcak in Santa Cruz. I helped him build a studio called Gadgetbox, which taught me about acoustics, wiring, studio gear, and the real guts of creating and running a recording studio. Andy also taught me a lot about how to run a business, taking on a debt to build something, building a clientele, and in general how to sustain yourself in the music industry.

“This was around 2008‑9. A year after Gadgetbox was up and running, I had gotten connected with Eric Valentine and he was looking for a new assistant. I’m a big fan of his work, and so took the jump and moved to LA. I ended up working for him for five years. Eric taught me how to record and produce music, particularly how to kind of lay the foundation of drums and bass and make sure that they can stand on their own.

“Tape and outboard were a big part of our workflow at his studio, Barefoot Recording. It was an incredible experience to be able to use all the outboard that people now use as plug‑ins, by UAD and Waves and so on. At the same time, he hammered the idea home with me that I should learn how to do things in the box, because everything would be going that way.

“I also love John Congleton’s work [Laurie Anderson, Lana Del Rey, St Vincent], particularly his use of distortion, and his tendency to misuse gear to get cool sounds. That really opened my eyes, and I rarely use a compressor to compress, but rather to destroy the signal and add excitement in that way. At 36, I’m lucky to have been steeped in analogue technology, yet in part because of my dad, I’ve also always been into computers. So I’m in that in‑between place where I still know how to use consoles and tape, and also how to work in the box.”

Outboard

Given the above influences, its unsurprising that Riordan’s studio contains some choice outboard. Before going into more detail on that, Riordan explains how he moved from working with Valentine to working with St Vincent. “I left Eric’s Barefoot three years ago, and after that worked at various different studios across LA. A couple of years ago I was hired to engineer a Sleater‑Kinney record [The Centre Won’t Hold, 2019], on which Annie was the producer. I already was a fan of her records, so when I was in the room with her, I found we got sounds very quickly, because we hear things in a similar way.

“Annie then asked me to work with her on some of her next projects. She has a home studio, with quite a bit of vintage gear, including a lot of outboard and many synths, and a 1970s 12‑channel Opamp Labs console, which is very left of centre. I helped her get into a workflow there and to execute her ideas. Sometimes that would involve me jumping on her drum set, as it’s faster for me to play it than program drums.”

Riordan’s work with Annie Clark at her Compound Fracture studio over time evolved into him helping her lay down some of the foundations for Daddy’s Home, including playing a drum part on the album’s lead single, ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’. “I think it’s the only song on the album I drum on,” explains Riordan, “and I also have an additional engineering credit on a few songs, because I was around at Compound Fracture for their genesis. For example, I recorded the main rhythm section for ‘Somebody Like Me’.

Riordan’s work with Annie Clark at her Compound Fracture studio over time evolved into him helping her lay down some of the foundations for Daddy’s Home, including playing a drum part on the album’s lead single, ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’. “I think it’s the only song on the album I drum on,” explains Riordan, “and I also have an additional engineering credit on a few songs, because I was around at Compound Fracture for their genesis. For example, I recorded the main rhythm section for ‘Somebody Like Me’.

“Working at Annie’s place was another reminder of the importance of outboard gear, because when you’re in the studio getting sounds, it’s faster for me to get something interesting by blowing up a compressor or distorting a Scully or things like that. It’s also more exciting. Annie is very instinctive and likes to work quickly, and is 100 percent OK with committing sounds. We don’t need to find a way back. With artists like her, using outboard gear makes sense.

“For her album it was all about: ‘How do we make things sound very, very classic?’ It’s an aesthetic that’s the polar opposite of her previous album. Ribbon microphones going through old equipment gets you halfway there, so once Annie discovered the sound of the record, that’s what we leaned on. She does her lead vocals at home by herself. She really got into the Beyerdynamic M160 double ribbon.

“This was a holdover from when we did quick demo vocals, and she wanted to quickly grab a mic and sing with the speakers on, and this worked well with the M160, which is supercardioid. In addition I lent her an RCA 44. All my mics stayed at her house during the pandemic, because I was mixing all the time, and had no use for them. Her mic pre typically was one of the Opamp channels, with some EQ added to brighten things. I’m a big fan of using ribbon mics with additive EQ from outboard.”

Home From Home

The timeline for the making of Daddy’s Home saw Riordan and Clark work at her studio for much of 2019, with some recordings that ended up on the album laid down by them during the winter of 2019‑20. In March 2020 they stopped working together, due to the pandemic. Clark later went to New York, to record most of the album with Antonoff and engineer Laura Sisk at Electric Lady. Where Masseducation had for the most part been mixed by star mixer Tom Elmhirst (Adele, Arcade Fire), in the summer of 2020 Clark asked Riordan whether he was interested in mixing Daddy’s Home.

“Typically, when someone asks you to mix an album, you reserve like two weeks or so, but in this case, tracks were trickling in as they were completed. I’d do a mix, send it back, they’d want to tweak the production some more, so they’d go back in, add stuff, take stuff out, and would send me their updates, and I’d try to find a way to reintegrate them into the mix session.

“Luckily everything was done in Pro Tools. Sometimes they’d work with stems of my mix, sometimes they’d work in my mix session. There always was some kind of master session. This was a process that went on over several months, in the end with Annie back in Los Angeles, where she’d update her vocals and guitar parts at her studio. Part of the challenge for me was to learn to embrace this way of working, as there were no limits on the amounts of revision and no time limit. Sometimes there were over 20 revisions on a mix.

“The changes kept coming, and a lot of decisions were made at the 11th hour, because the productions are so full, with tons of layers. Some of the productions weren’t really done until the last day of mixing. It was the Wild West! Obviously, there also were times that I was working on other projects. However, the most challenging thing of all was that I couldn’t invite Annie over during my mixes because of quarantine rules. We tried to work with video chat and streaming mixes using AudioMovers and video chat, but often it was easier to just print an MP3 and send it over.”

Gear

Riordan’s mix room at the time was in a studio called Casita Recording. “I had pretty much the same gear as I have at Pepper Tree, with ATC SCM25a monitors and dual Rythmik FV15HP 15‑inch subwoofers, a Dangerous Monitor ST controller, an iMac Pro with the newest version of Pro Tools Ultimate, and outboard like the Undertone Unfairchild, two Highland Dynamics BG‑2 compressors, two Undertone MPEQ‑1 Channel Strips, and a Federal 864 Compressor.

Riordan’s current mix room, at Pepper Tree Studio.

Riordan’s current mix room, at Pepper Tree Studio.

“The main thing I came out of the box for during the mixes was the BG‑2, which is great on vocals. I also sometimes used the Undertone mic pre to add high‑end EQ, and very occasionally real tape delay from an Otari MX5050 4‑track tape recorder, or a Roland Chorus Echo. The monitoring wasn’t as great as in my current room, for which I hired acousticians to really dial it in.

“The ATCs are very revealing, you don’t miss a lot of information on those. I have a pair of dual Rythmik subwoofers because back in the Barefoot days, Eric and I were really into having a lot of excess headroom in the low end for tracking. So I’m used to having giant subwoofers.”

Riordan isn’t only fond of big bass in tracking situations. A quick listen to the playlist of his mixes on his website makes clear that he loves big bass in his mixes as well, despite the fact that most tracks are in the alt‑rock genre. “Yes, low end is important to me. I’m a drummer and play bass, so it’s a big part of the equation. Also, I grew up listening to rock and hip‑hop. The hip‑hop of the late ’90s and early ’00s sounds incredible. For example Dr Dre’s records sound expensive, clean, and I just love the low end. I often listen to rock records and I think: ‘There’s something missing here.’ Tchad Blake’s mixes are an influence, for example of the Black Keys’ Brothers (2010), and with the Arctic Monkeys.

“I always think, ‘OK, how can I give this rock kick the same thump in your chest as an 808?’ Especially when you’re mixing in the box it’s all about headroom and managing the low end, and making sure it doesn’t fall apart by the time you get to mastering. If you haven’t done that well, and someone brings up the volume, your mix is going to fall apart.

“I know it’s an over‑used analogy, but mixing is like building a house. I tend to start mixing bass‑heavy. It’s more pleasant to listen to. I put a lot of work into thinking about where my 30‑50 cycles sub frequencies are coming from and where my 50‑100 cycles are. Once I start monitoring via compression and a limiter and getting the overall volume of the track up, I will start to tilt things back in balance, and add in more high end and midrange. Because I’ve built the track up from the low end, it is baked in, rather than having to add low end later and hoping it all comes together.”

House Music

Using his mixes of Daddy’s Home in general and of ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’ in particular as an example, Riordan goes into more detail about his mix methods: “We had a pretty good workflow with this project. Laura did a huge amount of prep before things came to me, which I really appreciated, so the sessions were already in really good shape when I received them. It made it very easy to integrate the sessions she sent me with my mix template.

“My template is mostly my busing setup. For example, I have a music bus, a vocal bus, and a drums bus, and they all have plug‑ins that I lean on a lot. With the drums, I have a clean drum bus, a parallel‑compression drum bus, and a distortion drum bus, that all go to the drums master bus. I also have my favourite effect sends, with slap delays and reverbs all ready to go. Obviously everything gets tweaked and modified to fit the song, but it’s nice to have a place to start from.

“My workflow was to prep the session in the evening, listen to it, get my bearings and then in the morning with a cup of coffee I hit play and listen to things in balance and roughly where the rough mix was left. Then I go to work. I also always have the actual rough mix on a separate output on my monitor controller and regularly reference that. In addition I’ll usually have some other sonic benchmark on another output on my monitor controller, so I can reference that as well. When I mix an album, the benchmark typically is the first song I mixed, because it kind of sets the tone for the rest of the album.

“As I said, I approach a mix as if building a house, so I start with the drums, get them going, then add the bass, and then the vocals, and get them to a decent standard. Then I’ll add the other midrange stuff, and build up the track. From then on it’s just warfare, trying to get the mix done. I’m moving with very fast and broad strokes, trying to get everything in order, and things will start sounding pretty complete in two to three hours. At that point I’ll take an ear break, and when I come back and it’s sounding good, it’s time to dial in the details, like automation, and so on. Sometimes after my ear break I do a Save As and try a different approach. If that works better after 15‑20 minutes, I continue with that. If not, I jump back.”

‘Pay Your Way In Pain’

Although it starts with some completely incongruous ’30s honky‑tonk piano, ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’ is influenced by ’70s glam rock, funk by Prince and Bowie (particularly ‘Fame’), and driven by a Moog bass synth riff, all underpinning Clark’s distorted and high‑attitude vocals. Clark and Antonoff play most of the instruments (drums, bass guitar, electric and acoustic guitars, synths, Wurlitzer, organ, sitar), and there are massed backing vocals by Clark, Antonoff, Kenya Hathaway and Lynne Fiddmont.

Cian Riordan: There was a lot of madness in this track, and I had to find a way of keeping the craziness, but also make sure things don’t sound out of balance.

Riordan: “I was around for the inception of that song when Annie came up with the riff, which sounds a bit like the Eurythmics, on the Moog Grandmother. It was the genesis of this song. We spent a day going through it, turning it into a loop, making it bigger, and me playing different drum ideas. When the song came back to me to get mixed it had transformed enormously, and they had added a lot of production on it. I was surprised to find that my drums were one of the drum sets that remained.

“I only very rarely got initial briefs for my mixes, and there was none in this case, so it was left up to me to work out what to do. One of the biggest challenges with this song was that there was a lot of creative panning. They were really making use of the stereo space, with things moving left and right, including drums and bass, that normally would be anchored in the centre.

“There were hard‑panned basses, also in other tracks on the album, but a sub‑bass in one ear is disorientating for the listener. So I would do things like filter out the low end in the sides of the bass, and then have a parallel bus, typically with a SansAmp, to get the low end centred, so your head wouldn’t spin off when listening on headphones. Jack and Laura also were into vintage echo and spring units, and in many cases they baked this into the sound.

“There were hard‑panned basses, also in other tracks on the album, but a sub‑bass in one ear is disorientating for the listener. So I would do things like filter out the low end in the sides of the bass, and then have a parallel bus, typically with a SansAmp, to get the low end centred, so your head wouldn’t spin off when listening on headphones. Jack and Laura also were into vintage echo and spring units, and in many cases they baked this into the sound.

“It’s your job as a mix engineer to be the bridge between the creative people behind the music and the reproduction systems of the listener. You don’t know if it’ll be listened to on headphones, speaker, a car, a club, and it’s your job to make it translate for all those environments. So there was a lot of madness in this track, and I had to find a way of keeping the craziness, but also make sure things don’t sound out of balance.

“Some of Jack’s heavier mix notes were about me being too heavy‑handed in getting the tracks back to a more standard approach. I’m glad he did, but it posed challenges for me, as in: ‘Hey, I’m a drummer and if the drums aren’t in phase and moving air through the speakers, I feel lost as a listener.’ So I spent a lot of time solving those kinds of problems. It was a lot of fun, because I ended up doing things I would not normally do.”

Drums

Riordan walks through some of the mix highlights. “Kit 1 is panned right. It was panned hard right and I brought it in a little bit. It’s an example of them being very wild, and me trying to make it sound more coherent. All drums go to a drum bus, which normally is unprocessed, but in this case the drums were so dynamic and punchy that I added a Waves Puigchild 660/670 compressor to soften the transients a bit. That compressor also adds some slight distortion that I like.

For his mix of ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’, Riordan relied heavily on FabFilter’s Pro‑Q 3 plug‑in. Here, it’s applying frequency‑selective expansion to the drum bringing back some of the transients that were compressed out earlier in the mix.“There’s a parallel drum bus, which has the Empirical Labs Arouser compressor, totally pinning the needle, and mixed in low, which makes things sound big and thick. Both buses go to a Drums Master bus. I’d added so much compression that I felt some of the transients were missing. I wanted the drums to hit more in your stomach, so I used the FabFilter Pro‑Q 3 for dynamic parametric expansion to bring some of them back. The Pro‑Q 3 is such a powerful plug‑in, just leagues above everything else. I also love the fact that FabFilter, and a company like iZotope, invent new tools and GUIs. I spend 10 hours every day behind a computer screen, so I like interesting new tools! There’s also a Waves Puigtec EQP‑1A on the Drums Master just to get the line‑level sound of it, and an Avid Lo‑Fi for some very minimal distortion.”

For his mix of ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’, Riordan relied heavily on FabFilter’s Pro‑Q 3 plug‑in. Here, it’s applying frequency‑selective expansion to the drum bringing back some of the transients that were compressed out earlier in the mix.“There’s a parallel drum bus, which has the Empirical Labs Arouser compressor, totally pinning the needle, and mixed in low, which makes things sound big and thick. Both buses go to a Drums Master bus. I’d added so much compression that I felt some of the transients were missing. I wanted the drums to hit more in your stomach, so I used the FabFilter Pro‑Q 3 for dynamic parametric expansion to bring some of them back. The Pro‑Q 3 is such a powerful plug‑in, just leagues above everything else. I also love the fact that FabFilter, and a company like iZotope, invent new tools and GUIs. I spend 10 hours every day behind a computer screen, so I like interesting new tools! There’s also a Waves Puigtec EQP‑1A on the Drums Master just to get the line‑level sound of it, and an Avid Lo‑Fi for some very minimal distortion.”

Bass

“There are two bass guitars played by Jack, one of them being a panned delay track, plus the Mother Bass main synth riff,” Riordan continues. “My challenge was to find space for the fun noodly bass guitars and the synth bass, and make sure it didn’t end up being a soup in the low end. I let the synth bass do all the heavy low‑end lifting, so I’m doing aggressive filtering on the low end of the bass guitars, using the Avid EQ3 7‑band, and then these two tracks go to a group, on which I had the Pro‑Q 3, cutting below 200Hz and above 10kHz. As a drummer I like a subby kick, but in this song the kick was quite knocky in the 70‑80 Hz region, so also for that reason I got the synth bass to take care of the sub bass.”

Vocals

“The keyboards and guitars were a matter of managing low‑end,” Riordan continues, “filtering, scooping frequencies and compression to keep things in check and sometimes to grab transients so things are not as pokey, and sometimes working with effects like chorus and phasing. Immediately below them is the Vocal Sub. So all the music goes to a Music bus, and all the vocals go to the Vocal bus, and from there to the Mix bus. I like to compress the music and the vocal buses separately.

“The vocal submix has the SoundToys Tremolator, which is an effect that is also on the Music sub. When I got the session the Tremolator was on the master bus, so I split it out onto the two buses so I could tweak them separately. I’ve also got a Slate Fairchild bus compressor, and the Vari‑Mu bringing out some of the highs and the high mids in a way that’s musical. I also use a bit of dynamic EQ with the Pro‑Q 3, to tame the 2kHz area.

“Most of the heavy lifting on Annie’s lead vocals is done on a Lead Vocal aux, which in turn goes to the Vocal group. The Lead sub has the FabFilter Pro‑MB, pulling out some of the mids, some overall compression from the Waves CLA‑76, I add some brightness with the Waves API 550A, then tame some harshness with the Oeksound Soothe, and another Pro‑Q 3 managing the high end. I have sends on the Lead Vocal track to two parallel distortion tracks VMon 351 and VMon SA, as well as the V Room aux.

The lead vocal track was multed out to apply parallel distortion, using SoundToys’ Decapitator and Avid’s SansAmp emulation.“The VMon SA aux has the SansAmp, and the 351 the Soundtoys Decapitator — in A mode it’s modelled on the Ampex 351. Both plug‑ins are set very aggressively, and sometimes the distortion triggered some harshness, around 3.5kHz and 7.5kHz, so I pulled that out of the source track. The V Room aux has the Eventide SP2016, which is my favourite room reverb. It sounds really musical, with a very natural high end.

The lead vocal track was multed out to apply parallel distortion, using SoundToys’ Decapitator and Avid’s SansAmp emulation.“The VMon SA aux has the SansAmp, and the 351 the Soundtoys Decapitator — in A mode it’s modelled on the Ampex 351. Both plug‑ins are set very aggressively, and sometimes the distortion triggered some harshness, around 3.5kHz and 7.5kHz, so I pulled that out of the source track. The V Room aux has the Eventide SP2016, which is my favourite room reverb. It sounds really musical, with a very natural high end.

“There’s another vocal track that features Annie singing the lead vocal with a different timbre, more breathy, and I put that through a pair of stereo Eventide H910 plug‑ins, to kind of stereo‑ise it a little bit more. The Eventide plug‑in suite is incredible, and the 910 has such a musical way of stereo‑ising something. These tracks are not super audible in the mix, they’re all drops in the bucket to making it sound wild.

“There’s also a scream track. It’s processed differently, so it’s in your face, and it has a similar 910 stereo thing happening. It also has some phasing from the SoundToys Phase Mistress.”

Master Bus

Finally, Riordan elaborates on the many plug‑ins on the Music Sub, and on his mastering plug‑ins: “The Tremolator and SoundToys Little Radiator on the Music sub were creative plug‑ins from Jack or Annie. I would either modify those or leave them alone. There’s also a Pro‑MB that gives a nice lift to the highs and lows, and the API 2500 is my template bus compressor. There are also two EQs on the Music sub, the Pro‑Q 3 and the Puigtec EQP‑1A.”

Active on the Mix bus are the Slate Virtual Tape Machine, iZotope Ozone, and the FabFilter Pro‑L2. “I love the Virtual Tape Machine plug‑in. When I was working with Eric tape was a big part of our workflow, and this is one of the few tape machine emulations that we felt actually did the things that we like about tape machines, like adding a low‑end bump and making the midrange less harsh. It’s certainly not distorting or anything.

“I got into the habit a couple of years ago of pretty early on in the mix stage getting the level of the track up to ‑11, ‑12 LUFS, so I’m monitoring at the level that the song is probably going to get mastered to. That helps me make decisions about how the low end is translating with this volume, so there are no surprises. So I’ll always have some sort of limiter on there, just so I can make sure I know what’s going on, and the Ozone is particularly great. Their Maximizer is a fairly benign way of adding level, as is the L2.”

Session View

Riordan’s mix session of ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’ is (by modern standards) a fairly modest 81 tracks large, though he stresses that there were dozens more tracks, which were all folded in or archived. The session is exceptionally well‑organised, starting with a Master track at the top, followed by a Music sub, and Music sidechain bus. Below this are audio tracks for three drum kits in blue, going to the Drum Sub, Drum Parallel and Drum Master group tracks, and percussion tracks in brown.

Riordan’s mix session of ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’ is (by modern standards) a fairly modest 81 tracks large, though he stresses that there were dozens more tracks, which were all folded in or archived. The session is exceptionally well‑organised, starting with a Master track at the top, followed by a Music sub, and Music sidechain bus. Below this are audio tracks for three drum kits in blue, going to the Drum Sub, Drum Parallel and Drum Master group tracks, and percussion tracks in brown.

Further down are bass tracks in red, with the Moog synth track called Mother Bass. The honky‑tonk piano intro and other keyboards are all in shades of purple. Jack Antonoff’s and Clark’s guitars and sitar are green, the Vocal sub aux, Lead vocal aux, Clark’s lead vocals are red and light blue, stacks of background vocals are in green and light green, and at the bottom are three aux effect tracks.

Download this ZIP file for a large, detailed view of the session screenshot: