What would happen if you upgraded every component in an 1176 compressor and added all the functions you wanted? One man set out to answer that question...

Lindell Audio are a company I'd heard little of until recently, but I was familiar with the name of the man behind them: Tobias Lindell is an award-winning producer at Sweden's Bohus Sound Studios (www.bohussound.com), and moderates a well-known online forum whose sole focus is boutique and high-end outboard audio gear. Given this, you'd have every right to expect that Lindell Audio's first outboard offering, their 17X mono compressor, would be something special.

Design Aims

The inspiration for this compressor is the UREI/Universal Audio 1176, which has proved very popular for good reasons but isn't perfect for everyone's needs. This being the case, there have been various different takes on the design: not only have UREI/UA released several different revisions, but several other companies have tried to improve on the design, or incorporate it within more fully-featured processors. Lindell's approach has been to trust his instincts and expertise as a producer, and create a high-quality compressor to suit his own style of working.

In part, that has meant adding things he feels are missing from the 1176. As with the Slate Pro Dragon, for example, you'll find high-pass filters for the compressor's side-chain, and a wet/dry mix control. The combination of these two features can make a huge difference to the degree of control you have over the sound. The side-chain high-pass filter enables you to make the compressor ignore prominent low-frequency (LF) content in instruments such as kick and bass. What this means in practice is that you can avoid unwanted pumping but achieve plenty of solidity, while leaving low-end elements on a bus, such as kicks and bass guitar, or the lower frequencies of individual instruments relatively 'unsquished'. There are five selectable high-pass frequency options for the side-chain filter: off, 100Hz, 200Hz, 300Hz and 600Hz, taking you well into the low mid-range territory of instruments such as guitar, snare drum and vocals. There are also fixed-frequency switchable high and low-pass filters for the audio signal. These slope gently at 6dB/octave, and should be useful for cleaning up rumble or other unwanted noises at the frequency extremes.

The wet/dry mix control is useful because it gives the user instant access to parallel compression without the need to juggle two separate controls to maintain the levels, or to tie up mixer channels. It's such a simple, yet incredibly useful feature that I can't understand why everyone (including UA with their 1176!) doesn't incorporate this into their processors!

It's not all about additions, though. There are fewer attack and release settings, for example: there are five stepped settings for each, compared with the seven available on the 1176. I have a feeling that the options are limited to five because that's how many stops are available on those tasty Telecaster switches, but it's not necessarily a case of style over substance: the available options seem well-judged, and I never felt that I was missing out. Other things, such as the five ratio settings (4:1, 8:1, 12:1, 20:1, and 100:1) remain the same as on the 1176, with the 100:1 setting resembling the 'all buttons' mode.

It's All In The Details

For those of you who are bothered about this sort of thing, Lindell told me that the starting point for his new design was a Revision F model of the1176... but he also stressed that this means very little in itself, given the degree to which he has tweaked the design and upgraded the components. I can see what he meant, too: the sheer quality exuded by the 17X and the attention to design details struck me as soon as I took one (I was sent two) out of the box. The front panel is reassuringly weighty, and the whole 2U-high metal rack casing has a pleasing solidity about it. The externally visible components are of high quality, too: there are gold-plated XLRs for the balanced I/O; the single, large VU/GR meter is a Sifam AL20SQ unit; some selector switches are Fender Telecaster types, as mentioned earlier, while smaller binary switches light up in the on position; and so on. The utility-chic khaki paint job ties everything together nicely, too.

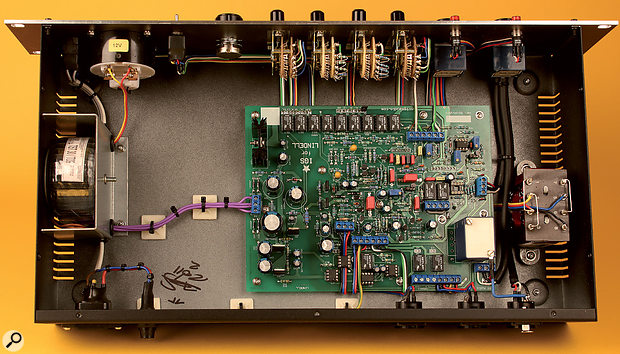

With the top of the rack case removed, the high quality of the internal components and the case layout is plain to see.Plenty of effort has evidently gone into giving this unit its aesthetic mojo, but the bits on the inside will have most impact on the sound — and removing the lid reveals a similarly lavish attention to detail. The pots protruding through the front panel are revealed to be ALPS rk27 types, for example, and the transformers are by Carnhill. These transformers are not necessarily technically 'better' than other designs: rather, they have a certain sound that some people like. There are several other high-end audio transformer manufacturers, such as Sowter, Cinemag and Lundahl, and each creates a number of transformer designs that will all sound different, according to the materials used and the manufacturing process. The initial goal of transformer manufacturers was to achieve galvanic isolation of an electrical circuit without significant changes to the audio signal (see Hugh Robjohns' review of the ART DTI transformer isolator for more on that), but while all hit the target of isolation, many coloured the sound in subtle ways, some pleasing to the ears of some people (though not necessarily of others!), and some less so. It's possible to overthink all this, of course, but Carnhill have developed a reputation for pleasant-sounding transformers, and Lindell has clearly arrived at this choice for reasons of sonic preference.

With the top of the rack case removed, the high quality of the internal components and the case layout is plain to see.Plenty of effort has evidently gone into giving this unit its aesthetic mojo, but the bits on the inside will have most impact on the sound — and removing the lid reveals a similarly lavish attention to detail. The pots protruding through the front panel are revealed to be ALPS rk27 types, for example, and the transformers are by Carnhill. These transformers are not necessarily technically 'better' than other designs: rather, they have a certain sound that some people like. There are several other high-end audio transformer manufacturers, such as Sowter, Cinemag and Lundahl, and each creates a number of transformer designs that will all sound different, according to the materials used and the manufacturing process. The initial goal of transformer manufacturers was to achieve galvanic isolation of an electrical circuit without significant changes to the audio signal (see Hugh Robjohns' review of the ART DTI transformer isolator for more on that), but while all hit the target of isolation, many coloured the sound in subtle ways, some pleasing to the ears of some people (though not necessarily of others!), and some less so. It's possible to overthink all this, of course, but Carnhill have developed a reputation for pleasant-sounding transformers, and Lindell has clearly arrived at this choice for reasons of sonic preference.

Unfortunately, quality costs, and the various component choices contribute to a price for the 17X that isn't for the faint-hearted. When I asked Tobias about the lofty asking price of this compressor relative to the Slate Pro Dragon, another augmented 1176 design that I'd perceived to be his main competition — it didn't bother him, simply because he believes his compressor to be better than its competitors: "I can only say that every single component I use is more expensive... It's an all ultra-high-quality unit, hence the higher price.” There was no arguing with that logic, so my next job was to find out whether this higher cost was justified by the unit's performance.

On Test

I mentioned earlier that I was loaned a pair of 17Xs. This was because the 17X, like the 1176, is a mono device, and I wanted the chance to try it out on the stereo drum bus (a favourite application of mine for the 1176), as well as on individual sources. I patched them both (via Sonic Core A16 Ultra converters) directly into my DAW test project, which contains a number of single sources and mixes that I regularly use to test and compare plug-ins and outboard gear. Unfortunately, I didn't have a hardware 1176 to hand, but I had recently conducted a number of listening tests comparing various revisions of the 1176 with several plug-in and hardware variations on the same theme, used on a drum bus, and so had some audio files that I could use as a useful point of comparison.

The first thing to note is that on all sources the familiar FET compression character of the 1176, with a hint of pleasing distortion, was clearly audible. The second is that, particularly when used on those sources with plenty of LF and low mid-range information to work on, such as bass, drums, guitar, and male vocals, I could clearly discern the enriching sonic effect of the Carnhill transformers, even when there was no gain reduction. I'd describe this as a pleasant, musically pleasing thickening of the sound. It's also a sound that, despite the deserved plaudits, I still don't think plug-in manufacturers have quite nailed. While I'm happy enough working entirely in the box, I'm reminded what I like about using outboard gear, and how much room most plug-in designs still have for improvement, the moment I run a signal through something like this! A final general point I'll reiterate is that the more restricted menu of attack and release settings wasn't a problem in practice.

My first subjective test was on a stereo drum mix, to ascertain how the 17X would behave on the drum bus — and it was here that, in purely practical terms, I encountered my first frustration, because two units cannot be linked for stereo operation. To be fair to Lindell, the two 17Xs seemed very closely matched, so it was a simple matter to match levels and all the side-chain control settings. But I could still hear a little shifting of the phantom centre image from time to time, as the two devices responded to their different side-chain signals. There are plenty of people happy working with this configuration (and Lindell's productions certainly demand more respect than my own!), but if you're one of those who's bothered by this, you'll probably find, like me, that you prefer using the a pair of 17X compressors on the Mid and Side (M/S) signals, rather than the left and right. That's easy enough to set up, and I actually often prefer M/S compression, given the greater control that this affords over a stereo signal — but it does still seem a shame that on a no-expense-spared device like this there's no on-board provision for linking two devices.

The rear panel features a subtle hint as to what genre this device is mainly intended for!As I said, though, that's a point purely about the practical application of these devices. Sonically, on the other hand, I had absolutely no complaints. Quite the opposite, in fact. I've mentioned the impact of the FET element and the transformers on the sound, but the controls available meant that I could access the amount of compression and character I required very quickly. The settings were clearly visible at a glance, thanks to the choice of switches and clear legending on the front panel. Both the high-pass side-chain filters and the wet/dry blend controls usefully extended the range of sounds available, enabling me to achieve anything from subtle compression, with a low ratio and with the blend control backed off to mostly dry, through to over-crushed big-beat drums, by way of pretty much anything you'd want from a 'character' compressor in a rock/pop mix. When I say subtle, note that I don't mean transparent, as the overall sonic imprint of this compressor's analogue circuitry was very much evident at all times. As is so often the case with well-designed hardware, I noticed that if I wanted to, I was able to raise the overall level of the drums way beyond what I could achieve with any plug-in, and all without clipping my converters. Whether that's important, or whether that's a sound you like, will be very much down to you!

The rear panel features a subtle hint as to what genre this device is mainly intended for!As I said, though, that's a point purely about the practical application of these devices. Sonically, on the other hand, I had absolutely no complaints. Quite the opposite, in fact. I've mentioned the impact of the FET element and the transformers on the sound, but the controls available meant that I could access the amount of compression and character I required very quickly. The settings were clearly visible at a glance, thanks to the choice of switches and clear legending on the front panel. Both the high-pass side-chain filters and the wet/dry blend controls usefully extended the range of sounds available, enabling me to achieve anything from subtle compression, with a low ratio and with the blend control backed off to mostly dry, through to over-crushed big-beat drums, by way of pretty much anything you'd want from a 'character' compressor in a rock/pop mix. When I say subtle, note that I don't mean transparent, as the overall sonic imprint of this compressor's analogue circuitry was very much evident at all times. As is so often the case with well-designed hardware, I noticed that if I wanted to, I was able to raise the overall level of the drums way beyond what I could achieve with any plug-in, and all without clipping my converters. Whether that's important, or whether that's a sound you like, will be very much down to you!

So happy was the experience of using the 17X on the drum bus that I decided to try them on the mix bus. That's something I rarely do with the 1176 unless I've got it set up as a parallel effect, because I find that with its lowest 4:1 ratio, it's not gentle enough. However, I suspected that the 17X would be up to the job, given the control afforded by the mix and side-chain filter controls. I fired up a large multitrack project, began mixing into the pair of Lindells in an M/S configuration, and found myself aiming for roughly 3dB of gain reduction on each. Again, the Lindells seemed to control things effortlessly, and I was pleased with the result. But how can I best convey the experience of using them in this role? You could say that it was rather like having a hybrid compressor, with the basic character of an 1176 but with a slightly Neve-like feel, which, presumably can be attributed to the Carnhill 'iron'. I often found that I was rather thrilled by the result of 'crushing' things just that little bit more than I usually would on the bus, and then backing off the blend control to around a 50:50 wet/dry mix.

I also tried treating various mono sources, and while I wouldn't necessarily want to treat every single track with the same compressor, I'd probably be able to press the 17X into service on pretty much anything. I won't dwell on the details too long, as I'm otherwise going to be in danger of repeating myself — because the same features (the sound of the transformers and analogue electronics, the side-chain filter, and the wet/dry blend control) seemed to win through every time. As in the mix-bus role, these features made the 17X very usable on sources I'd not usually process with the 1176, including acoustic guitar. I was very happy using it on bass, kick and snare, too, and the subtle distortions imparted by the circuitry were particularly pleasing on distorted electric guitar and on vocals, especially the low-mids of male and the breathier regions of female vocal tracks.

Verdict

Do I like Lindell Audio's 17X? Yes, absolutely. In fact, if I were pushed to choose one compressor to add to my rack and budget wasn't limited, I'd probably opt for one of these. Or, rather, a pair of these. That's partly down to my own taste, of course, but I'd expect anyone mixing material in the pop, rock or urban genres to enjoy this processor. If you're after a clean, clinical compressor, or a transparent mastering unit, it's probably not going to meet your needs (although I'd still urge you to investigate what it can do).

I'm left with only two criticisms, neither of which are major. The first is the lack of stereo linking, which is not an insurmountable problem, and the second is the price: it's a professional price tag for a professional product. You have to respect Lindell for choosing not to cut corners in this design, and if you've set aside a substantial pile of cash for a great compressor, I strongly recommend checking out the 17X.

Alternatives

The 1176 itself is obviously an alternative in some respects, but all versions of it lack the signal and side-chain filtering and the parallel-compression functionality. What strikes me as being the nearest competitor is the Slate Pro Audio Dragon, which is another mono parallel compressor, featuring side-chain filtering and more besides. The Dragon is rather less expensive (albeit not exactly cheap) and is probably a little more versatile than the 17X, but it offers a rather different sonic character — and I have to say that I did prefer the 17X in this respect. Setting aside the job of compression for a moment, and thinking in terms solely of the sonic effect of the analogue circuitry, you could consider the various classic designs from Neve, such as their 2254/R.

Pros

- Offers so much more than an 1176.

- Looks great.

- No expense spared on quality of components.

- Offers both direct and mix outputs.

Cons

- No external side-chain input.

- Can't be linked for stereo operation.

Summary

The Lindell Audio 17X is a beautiful-sounding compressor that's reminiscent of the classic Urei 1176, but offers a few useful extra features that open up a much broader tonal palette, ranging from subtle parallel effects to full-on drum-loop slamming.