Immersive audio is a powerful way of presenting live music — and it’s becoming more and more accessible to independent artists.

When I delivered my first immersive set in 2019, the addition of spatial audio was not something that had even crossed my mind. At the time I was gripped only by the desire to create a show uniting electronic music with visuals — creating something to take an audience out of their day‑to‑day experience — and was working with designer Jan Petyrek to achieve this.

Jan and I were searching for venues to test out our nascent AV set when we were offered a last‑minute slot at a Hackathon event at Abbey Road Studio 2, the aim of which was to encourage participants and performers to innovate. The company providing the sound system, L‑Acoustics, explained they were bringing a 12.1 system into the venue, and suggested I might like to program the set for this setup. This seemed intriguing, and with encouragement and guidance from their engineers I was able to reformulate my set using their L‑ISA software in just a couple of days.

Live For Live

Like many electronic music producers, I use Ableton Live for both production and performance. For my live sets I was already used to bouncing audio of each track into component stems such as kick, percussion, bass, effects and synths, and placing these into a number of scenes in Ableton, with each scene triggering a whole track. I would then add a variety of instruments and samplers into the Ableton set to play live over the audio playback.

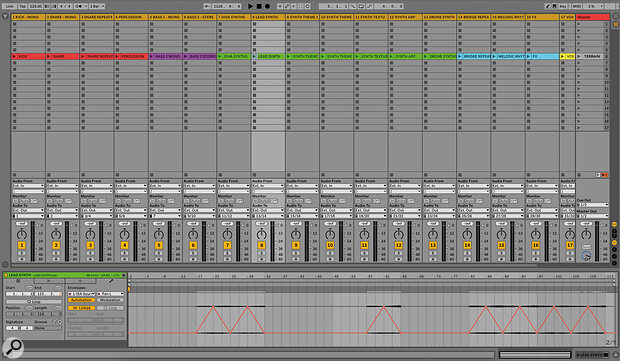

The author’s setup uses Ableton Live and L‑ISA from L‑Acoustics.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

The author’s setup uses Ableton Live and L‑ISA from L‑Acoustics.Photo: Chloe Hashemi

The first time working in L‑ISA introduced me to the now‑familiar process of stemming my tracks in a much more granular way to create audio objects for spatial mixes. In brief, spatial audio gives you the opportunity to place and animate all of these audio objects, aka sound sources, independently within the auditorium. An L‑ISA Processor — either physical or virtual — maps the objects to the physical speaker array to convey the spatial mix you have created. The programming to achieve a spatial mix involves adding metadata to each created audio object. (For more about the principles of object‑based mixing, see our 'Introduction To Immersive Audio' article in the January 2022 issue.)

Metadata can include information about panning, elevation, and even effects such as distance created through the addition of dynamic reverbs. These can all be changed over time, either using snapshots within the software engine or — as felt more comfortable in my workflow — using L‑ISA plug‑ins in Ableton Live and drawing in automation. These then communicate with the L‑ISA Controller, which integrates information for all your audio objects, speaker setups and monitoring options and also includes a spatial effects engine.

These days, I might create between 10 and 20 stems depending on the project. The idea is to achieve a good balance between the number of outputs and programming required, and the flexibility to treat sounds differently. As an example, if you bounced a synth and a vocal sample together in the same stem, they would receive the same metadata and would be placed in the same way around the room, which may not be the desired effect. However, you can group multiple granular stems in the L‑ISA software if you actively want them to receive the same metadata; for example, you could group a number of synths together and place them around the room in one go.

The L‑ISA plug‑ins allow spatial audio metadata to be written directly into a Live session.

The L‑ISA plug‑ins allow spatial audio metadata to be written directly into a Live session.

Advance Planning

For that first project at Abbey Road, the main challenge was monitoring, and this is still a key issue for the development of immersive sound today. At that time, the only way to audition my programming was within a multi‑speaker monitoring setup, and I completed much of the object‑based mix at the L‑Acoustics Creations showroom studio in Highgate with an 18.1.5 studio speaker array. In the words of Ferris Bueller: “It is so choice. If you have the means, I highly recommend picking one up.” But that luxury isn’t often available, and many people need a more affordable and portable way to test out their panning and effects choices.

In 2021 the launch of the L‑ISA Studio suite brought the addition of binaural headphone monitoring, a feature also available in other popular spatial audio software such as the Dolby Atmos Renderer. Binaural monitoring uses psychoacoustic techniques to emulate how we perceive sounds coming from behind or above us. There is also the option to use a head tracker, which allows a more fully realised rendition of a 360‑degree space, constantly reinterpreting the sound as you turn your head. In my experience, binaural monitoring has never sounded exactly like the eventual room setup, but it gives a clear enough idea of the movement of sound objects to enable me to program a set using headphones. Even for reproduction in stereo, a venue can sound radically different from a studio mix and require some adjustment, so I don’t think spatial audio brings any new challenges here.

That initial, experimental Hackathon opened a door for me to consider using spatial audio in future shows, adding to the palette of options with which to create immersive experiences. It had particular relevance to my practice, as the compositions ranged from pure sound design — delivered all around the audience — to beat‑driven IDM tracks, which benefit from a static frontal image (kick, bass and so on) enhanced with effects and synths placed around the...

You are reading one of the locked Subscribers-only articles from our latest 5 issues.

You've read 30% of this article for free, so to continue reading...

- ✅ Log in - if you have a Subscription you bought from SOS.

- Buy & Download this Single Article in PDF format £1.00 GBP$1.49 USD

For less than the price of a coffee, buy now and immediately download to your computer or smartphone.

- Buy & Download the FULL ISSUE PDF

Our 'full SOS magazine' for smartphone/tablet/computer. More info...

- Buy a DIGITAL subscription (or Print + Digital)

Instantly unlock ALL premium web articles! Visit our ShopStore.