For Spike Edney, touring with one of the biggest bands in the world has meant keeping up with the very latest in stage keyboard technology.

It’s 1984, and Spike Edney is just a few gigs into his new job with Queen as their touring keyboard player and occasional guitarist. Among the keys set out discreetly to one side of the stage at the Birmingham NEC is his Roland Jupiter‑8, and just as the set is about to move to that year’s big hit, ‘Radio Ga Ga’, Spike accidentally knocks one of the Jupiter’s controls.

“It was the slider that adjusted the arpeggiator’s tempo,” he recalls, “and it had only about an inch of travel, from zero to a million — very sensitive. Hung around my neck on that tour I’d have a little Casio thing with a metronome that I’d use to manually set the arpeggiator for ‘Radio Ga Ga’, and normally this would take quite a few minutes to do. But my heart sank, because there wasn’t time for any of that. Roger Taylor points at me, goes, ‘Two, three...’ and I had no choice but to press the key.”

Instead of the relaxed arpeggiating groove that 40,000 fans might have expected, out came a manic blur of machine‑gunned notes. All four members of Queen glared at their new keyboard player. “It’s the only time in my career that I held up my hands and said, ‘I don’t know what on earth happened — carry on without it!’ And that was my third gig. I was really expecting shit after that,” he says, laughing, “and to be fair, eyebrows were raised. So in order to save my arse, I deflected. I said that something went wrong with the machine. And since then, I’ve had this motto: Technology will fuck you up.”

Just Another Gig

It all began for Spike in the usual teenage bands in his home town of Portsmouth, which led to gigs in the ’70s playing keyboards for the likes of soul legends Ben E King and Edwin Starr, and on to ’80s tours playing trombone with everyone from Duran Duran to Thomas Dolby and Dexys Midnight Runners to the Boomtown Rats. In the ’90s he worked in Brian May’s and Roger Taylor’s solo groups, and also formed Spike’s All Star Band (SAS Band), which has featured a host of special guests over the years, including Roger Daltrey, Jeff Beck, Kiki Dee, Ian Anderson, Jack Bruce and Ronnie Spector.

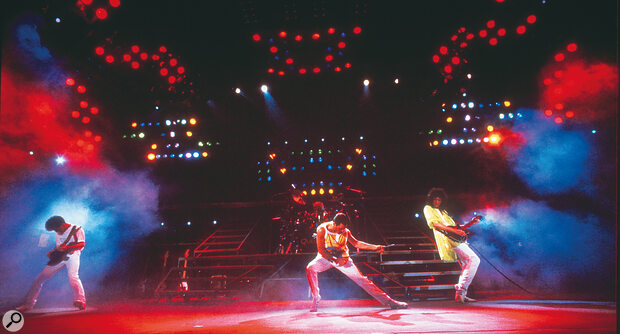

Queen on their 1986 Magic tour, their last with original frontman Freddie Mercury.Photo: by Denis O’Regan, copyright Queen Productions Ltd

Queen on their 1986 Magic tour, their last with original frontman Freddie Mercury.Photo: by Denis O’Regan, copyright Queen Productions Ltd

Since his two‑year live stretch with the original Queen line‑up, which stopped touring after the Magic outings of 1986 and ended upon Freddie Mercury’s death in 1991, Spike has toured with all the later versions of the band. Alongside Brian May and Roger Taylor, at first in 2005 this was with ex‑Free and Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers, bassist Danny Miranda, and guitarist Jamie Moses; since 2012, the line‑up has featured vocalist Adam Lambert, bassist Neil Fairclough, and percussionists Rufus Tiger Taylor or Tyler Warren. The most recent Queen gig — Spike describes it as “a last‑minute dash” — was at the Taylor Hawkins tribute concert in September 2022.

Back to 1985, though, a year after the Jupiter mishap, and the chance came for Queen to play at something called Live Aid. Spike remembers the band thought it no big deal. “It was another gig,” he says. “Another short gig.” Twenty‑one minutes, in fact. Twenty‑one minutes that would make Queen even bigger stars than they were already.

“I was in Bermuda doing a gig with a mate, a gig holiday, and I had to come back,” he remembers. They rehearsed for two days at the Shaw Theatre in London and worked out a medley to fit the allotted time. “Queen were always big on medleys, because there’s so much material. It’s the way to give an audience more bang for their bucks. We sat out around a wooden picnic table, a beautiful day, I had my Casio thing that also had a stopwatch in it, and it took us a few minutes to decide the songs to include.”

Then they pieced them all together, chopping and adapting to suit. “We tapped it through and I timed it. So OK, we’ll start with ‘Bo Rhap’, up to the end of the guitar solo, then straight into ‘Radio Ga Ga’, a shortened version of that. Once we’d figured out the timing through to ‘We Are The Champions’, we went back in, said right, let’s play ’em and join ’em up. But it was not a big deal.”

It helped that Queen understood what was required and that they delivered. “Play your biggest hits, and play as many of them as you can fit in, and you will please more people,” Spike explains. It sounds obvious, but it wasn’t a scheme widely adopted at Live Aid. “I was gobsmacked by how many on that show did one or two songs with extended guitar solos forever. Or played their new single. I think we gauged it right — and I was still very much the new boy, learning all the time about how they put things together and their viewpoint on stuff. I learnt an awful lot, which stood me in good stead later when, among other things, I was musical director for the Nelson Mandela 46664 benefit concerts for AIDS.”

Come the day of Live Aid, Spike recalls a great sense at Wembley of everyone being there for the right reasons, and that the band’s main worries — without a soundcheck, naturally — concerned getting on, hearing everything, and getting through unscathed. “That was the order of the day: play what we know; don’t cock it up. We came off after our six songs in 20 minutes, and it was a case of OK, job done. Simple as that.” Except?

“Except, of course, the hysteria started the next day,” he says, smiling at the memory. “Queen this, Queen that. And it just grew and grew over the years. Now you get, ‘Oh, the greatest gig ever!’ and all this kind of stuff. Well I think that’s a load of old bollocks, myself. It was a band at the top of its game doing what it does, and doing it well. I do understand that people want it to be some magical thing where we all descended from the heavens, but no. It shows you what experience and a sense of occasion can produce.”

The DX5 & The Wardrobe

Spike’s gear had taken a few shifts in the meantime. A few months before Live Aid, in May ’85 at the conclusion of the Works tour, Queen played some dates in Japan, and Spike took advantage of some time off in Tokyo to go tech‑hunting. First stop saw him bag a Sony twin‑cassette Walkman, and then he moved on to the Yamaha building.

“The DX7 was all the rage then. So many records at the time were using its very clean sounds. I used one in the studio now and then, but it had this very peculiar digital sound to it, and I was still in love with big fat analogue noises. So I was not much of a DX7 fan. But I went into the building, and in their showroom was the glorious DX5 — which was more or less two DX7s in one. I played that, and it changed everything — all of a sudden it had some real depth and width to it.”

He asked where he could get one, but it was a few months away from release and he was told this was demo only. “I said you’ve got to get one to me, and told them what we were doing. I said ‘I need it!’ So I think I was one of the first people to get a DX5, and that’s what I used on the ’86 Magic tour. By that time my setup was the DX5 as my main keyboard, plus an Emulator III, which I’d use for its rather boxy‑sounding sampled piano — certainly no match for Fred’s Steinway or whatever it was — and the old Jupiter‑8, which was wonderful for its thick, analogue, paddy sounds, plus a Roland vocoder for ‘Radio Ga Ga’. That took me through the whole of the Magic tour up to Knebworth in August ’86, which was Fred’s last gig, although of course we didn’t know that at the time.”

Spike worked with Roger Taylor’s Queen offshoot, The Cross, from 1988 through to 1990. It was around this time that he rebelled against the X‑frame stands that were de rigueur at the time, and developed something more substantial. “I refused to use those stands. They really turned me off. I thought ‘This is not good for the soul, boy.’ So I had my first B3‑type cabinet built. It was known as the wardrobe, because that’s what it looks like. We had a cinema props carpenter copy the Hammond, and he measured up my three keyboards — the DX5, a two‑manual Korg organ, and the Vocoder — so it was four manuals in a box. I’ve still got it today and use it with my SAS Band.

“We had a lot of fun,” he says of his time with the Cross. “Got slagged from beginning to end, apart from a clutch of very loyal fans who loved us and still do, but the press hated us and the records didn’t sell. Looking back, I do think they were good records.”

From there, he worked for a while in the other Queen offshoot, Brian May’s band, playing on a number of records and tours through the ’90s. The wardrobe didn’t make it for that, because the idea was to have a lighter setup, and Spike used a Roland A‑series keyboard controller MIDI’d to a number of Roland modules. “It was the first time I ever used a MIDI system with stuff built into a rack,” he remembers.

Spike Edney and his ‘wardrobe’ keyboard stand, which was originally built to house a Yamaha DX5, a dual‑manual Korg organ and a Roland Vocoder.

Spike Edney and his ‘wardrobe’ keyboard stand, which was originally built to house a Yamaha DX5, a dual‑manual Korg organ and a Roland Vocoder.

Sheet Music

There was also the hugely successful Queen jukebox musical We Will Rock You, which opened at London’s Dominion Theatre in 2002. Spike had been asked to take part, and he figured it presented a good opportunity to upgrade his instruments. A chance meeting with Korg product manager Alan Scally at a NAMM show in Anaheim started a long‑term love affair with Korg keyboards.

The We Will Rock You organisers had told him there would be three keyboard players plus a keyboard‑playing conductor. “I thought that was bloody ridiculous,” Spike recalls. “Four keyboard players at a Queen gig? There’s barely enough for me to play!” But anyway, he got to talking to Alan about the Triton workstation that was on show at Korg’s stand. “I told him who I was and that I’d been asked to do the musical, that I believed we were going to be using four keyboards, and would Korg be interested in sponsoring this? And he said ‘Yes indeed!’”

Once he got home, Spike wondered if in fact he could bear life as a pit musician, but he was told he could do it for six weeks and then leave if he wanted. “I agreed to that, and then I said about the deal with Korg I’d lined up. ‘Oh no, no, no, we only use Kurzweil, and we’ve already bought them.’ You’ve bought them? I was getting this stuff for nothing! But we ended up using the Kurzweils. I never thought much of them, and I thought the Korgs would have been a better bet.”

His misgivings about the theatre job began to grow. The prospect of full employment for a while was certainly attractive, but there were other worries. In rehearsal, Spike and the band began to play ‘Somebody To Love’, but the conductor called a halt after a few bars. “He looked at me and said, ‘That’s not how it goes.’ I assured him that it was. I said ‘This is how we’ve played it since 1984, and I was taught it by Freddie Mercury!’ He said, ‘No, you have to read the chart.’ I repeated that I knew this stuff, that I’d played it a great deal.”

After some more of this to‑and‑fro, Spike, who admits his sight-reading isn’t great, figured out what the chart was doing, and said it was nothing like the way Fred played it. He concluded that he wasn’t going to last in this environment, not least because it was all going to sound wrong to him. So at the end of the six weeks, he prepared to leave. He was advised, however, that he could continue and put in deps if he wanted to have days off.

“I said really? I didn’t know about that.” Spike pauses for yet more laughter. “I then went about finding as many deps as I could — in the end I think I had 14 deps, and at any one time I had half a dozen on the go. And then I would work whenever it suited me. I would take months off at a time. And I kept a lot of piano players working for a long time. I was gobsmacked by that skill — very respectful of the people who can do that. So anyway, a six‑week engagement at We Will Rock You turned into 14 years.”

Backup Plan

Spike’s setup for the post‑2012 version of Queen, which features Adam Lambert fronting the band, has been consistently Korg‑based. He reckons the story of how that came to be provides a good insight into the life of the touring keyboard player. Picture a large stage somewhere in Australia, in the middle of a Queen tour, in 2014.

Spike Edney (far right) takes a bow at a Queen + Adam Lambert show in 2014.Photo: Creative Commons licence 2.0: flickr.com/bobnjeff

Spike Edney (far right) takes a bow at a Queen + Adam Lambert show in 2014.Photo: Creative Commons licence 2.0: flickr.com/bobnjeff

“I had the wardrobe, my cabinet meant to resemble a Hammond B3 — although it actually looks more like a post‑office counter. People used to say I was half man, half desk. So anyway, I’m there looking at my Korg Kronos, and I said to my tech at the time, ‘If anything ever went wrong — touch wood, heaven forbid — do I have any kind of backup or spare?’ He said yes. ‘Oh, so where is it?’ He said ‘Well, at the moment it’s out in the truck.’ I said ‘Hmmm, we should maybe have it a bit closer than that. Why don’t we try having it right here next to us?’ I was thinking yet again of my motto: Technology will fuck you up. It’s going to happen one day, and probably at a really important moment. As they’re counting in ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, let’s say.”

Spike asked the now worried‑looking tech how long this backup keyboard took to be ready to play from cold. “He has a think, says ‘Oh, about seven or eight minutes.’ I said ‘What! You mean I’m looking at you getting that keyboard out of its box, putting it into the post office counter, and seven or eight minutes later I can play something?’ I said ‘How do you think that’s going to go down at the beginning of “Bo Rhap” when Roger counts me in and I point at you? What do you think’s going to happen?’ And he said, ‘Never really thought about it.’ I said, as calmly as I could, ‘Well, shall we think about it now?’”

Spike gathered together Queen’s tech folk and they agreed that a second Kronos, plugged in and ready to go with duplicate sounds and settings, was quite a smart idea. It meant another level added to the post‑office B3, and it meant that Spike could relax a little behind it.

The Good Ship Nautilus

More recently, Spike has been enjoying a much posher housing for his keys. During Queen’s Rhapsody tour, which ran in various chunks from 2019 to 2022, he began to use “something that looks like a Steinway grand piano case”, which was originally planned to enclose the two Kronos keyboards, main and backup.

Spike Edney: My roadie had to go and commandeer a Nautilus from the local shop, under much protest because it was the only one they had — I think we bribed the guy with some tickets for the show...

“And for the first time ever in my career, I played sitting down,” he says. “I’d never done that — I’ve always been a stand‑up man. But, you know, I turned 70 this year, so I guess it’s quite dignified for me to sit there. Also, I think they wanted to give it a grander, more operatic vibe, because the Rhapsody stage set was like you’re in an old opera theatre. So I understood it. And it was miles better than the post‑office counter, I have to tell you.”

During a rehearsal for the 2022 leg, however, Spike’s Kronoses started to misbehave. They had lived a long and hard life, and Korg had already suggested that Spike might like to retire them and try their new Nautilus. “Being an old guy and resistant to change, I’d said no. Why would I change? I’d have to learn a new system. I’m happy with the old ones, I know how to fix things instantly. But now I had little choice. By about the fourth gig in, I was in Glasgow, and my roadie had to go and commandeer a Nautilus from the local shop, under much protest because it was the only one they had — I think we bribed the guy with some tickets for the show and he released it. We did a really quick data transfer, and there I was, newly converted to the Nautilus after a crash course. And I must say it’s been fantastic.”

After the Glasgow gig in June ’22, with the new Korg installed, the next date was something of a big one. “We were opening at the Queen’s Jubilee in front of Buckingham Palace,” Spike reports. “So you can imagine the kind of tension I was going through, thinking ‘Oh my God, is this going to be the greatest cock‑up of all time?’ But the Nautilus was good. And it saved us. Which was just as well, because from there we went on to 10 days of sold‑out shows at the O2.”

He likes the ease of use of the Nautilus, and the main hurdle he faced was to overcome the inevitable differences between what he was used to with the Kronos and the way the Nautilus operated. “It was things like slight changes to where the pages come up, how you get into edit mode, stuff like that. I’m ageing and I use glasses, so I would love if they would allow it to connect or Wi‑Fi to my iPad, which I use for notes and various other bits and pieces.”

This year, Spike swapped out his Korg Kronos setup for a pair of Nautilus keyboards, pictured here in the Steinway‐style housing used for Queen’s Rhapsody tour.

This year, Spike swapped out his Korg Kronos setup for a pair of Nautilus keyboards, pictured here in the Steinway‐style housing used for Queen’s Rhapsody tour.

Splitting For Ga Ga

Any teething problems Spike had with the Nautilus were vastly outweighed by its positives, and one of his favourite things is its set‑list feature. “On tour, for example, we might make changes if we get bored, moving songs around, seeing what they feel like, and it’s great to be able to just copy the set list, edit it, and there you are — and you’ve still got your original, so I can go way back to set lists for the past God knows how many years. It’s a great facility. I normally have eight combos on the screen, and that leaves me two‑thirds of the screen to put notes, like ‘Wait for drummer’ or ‘Do not count this song in until singer is ready’, or lyrics that I cock up because I can’t remember the difference between verse one and verse three.”

He also loves the ease with which he can use keyboard splits, which are essential for some of the songs in a Queen set. “Still the most complicated song I have is ‘Radio Ga Ga’. On the left side of the keyboard I’ll have an octave of that arpeggiated bass thing that starts it off. Then there’s a regular piano and strings, layered, with the strings brought in with a volume pedal. And up at the high end of the keyboard I have a vocoder, so I can do the ‘ray‑dee‑oh’ bit. And that’s the whole song right there.”

Sometimes he’ll split the Nautilus keys to provide piano, strings, and maybe an octave of organ to one side for, say, ‘Under Pressure’, where the organ only appears in the middle eight and doesn’t require a whole keyboard. Generally with Queen it’s pretty straightforward. And this is no bad thing, he says. Allied to his technological motto is Spike’s admirable inclination to keep things relatively simple.

“I’ve always said that you should be able to do a gig with a decent piano, decent strings or pad, and a decent organ sound,” he reckons. “That should get you through most things. That’s what I always start with: what must I absolutely have? I’ve never been one for having little dingly digital bells and effects and stuff, because I find that they complicate things and get in the way. And with a loud guitar band like Queen, all of that stuff would just be lost. In the studio, of course, you can have endless combinations of nuanced bits and pieces. But in front of 50,000 people in a stadium? I’m afraid a lot of that stuff will just be fighting to be heard.”

The Synths Of Our Fathers

So what’s it like still to be playing with the latest incarnation of Queen nearly 40 years since he started with the original line‑up? “It’s always a challenge, and it’s always about not cocking it up,” he says, smiling once more. “And when you’ve got quite a few thousand people out there, it’s such a blast and it’s such fun. The quality of the playing was always great, and still is. To be part of that is wonderful, and that’s never gone away.”

To conclude, we’re back in Portsmouth in the very early ’70s, and the 18‑year‑old Spike is off with his bandmates to see Robert Moog give a talk at a local venue. Basically, Robert was in the UK to tell the story of the Moog synthesizer so far. Spike found it all interesting, even if a lot of what was said was technical. But at this time, very few people really knew yet what a synth was or could do. “And then at the end, Robert Moog said, ‘I can see a time when every band will have a synthesizer, in the same way that it has a guitar now.’ And the whole place burst out laughing. It was like him saying ‘I believe every band will have a hot‑air balloon.’ We laughed all the way to the pub — we were saying that all these synths really do is make space noises, wee‑yow wee‑yow, that you could do with a swanee whistle!"

“And of course, within a couple of years we all had one...”